Months After Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico Still Struggling

The new death toll from the worst natural disaster to affect the island is a reminder of the longest blackout in U.S. history.

Nearly a year after Hurricane Maria wreaked havoc in Puerto Rico, Ricardo Rosselló, the island’s governor, raised the storm’s official death toll from 64 to 2,975. The figure comes from a new study by the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. Rosselló commissioned the study and acknowledged this week that he made mistakes. On Wednesday, President Donald Trump said the federal government did a “fantastic job” in responding to the storm.

But in February, Yamary Morales Torres, 41, told me, “The fishermen here are suffering,” as she stood in her yard overlooking the pounding surf on Puerto Rico’s southeastern coast. Setting out before daybreak, Yamary and 14 other fishermen in her neighborhood have to prepare their boats and fishing gear in the dark. In addition, “there’s no place to refrigerate the fish we catch, so we need to sell them immediately.”

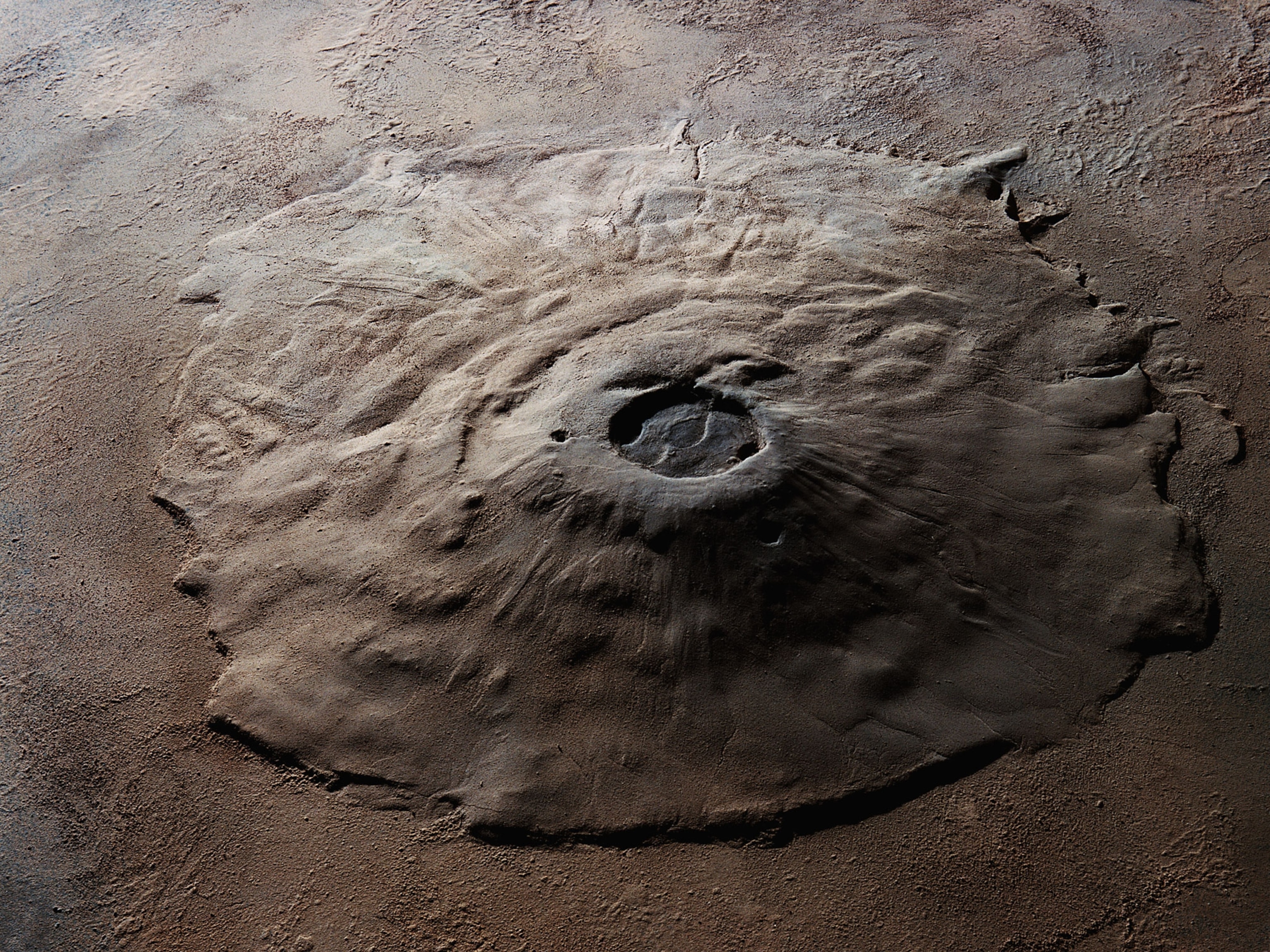

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria struck land not far from Playa El Negro in Yabucoa, where Yamary and her extended family live. The storm knocked out power to the entire island, a United States territory that is home to 3.3 million citizens. Five months later this neighborhood of only 14 homes—all damaged and flooded by the storm—still had no electricity and no sense of when it would be restored.

A third-generation fisherman, Yamary lives with her elderly parents in their dilapidated concrete home. The house next door was all but leveled in the storm. Her twin sister, Yasmin, lives two houses down, next door to a brother and his family. They all had to evacuate before the storm, but with no other options the family returned to their lifelong homes. “Life is very sad now,” Yamary says. “But I’m not leaving. I’m staying right here.”

A third-generation fisherman, Yamary lives with her elderly parents in their dilapidated concrete home. The house next door was all but leveled in the storm. Her twin sister, Yasmin, lives two houses down, next door to a brother and his family. They all had to evacuate before the storm, but with no other options the family returned to their lifelong homes. “Life is very sad now,” Yamary says. “But I’m not leaving. I’m staying right here.”

That spirit of resilience is helping Puerto Rico rebuild from the massive destruction left in the storm’s path. Power and water were restored within weeks to the island’s major urban areas, but with spring approaching, more than 100,000 residents—all in rural, poor areas much like Playa El Negro—remained in the dark. It’s going to take more than determination by the island’s residents to fully recover, if that’s even possible.

The strongest storm to hit Puerto Rico in 89 years, Hurricane Maria battered the island with tornado-force winds. Massive rains brought catastrophic flooding, washing out bridges and inundating entire neighborhoods. The island’s infrastructure, already shaky after years of neglect, was devastated.

With no power, running water was cut off for much of the population. Communications to and from Puerto Rico were nearly impossible for days. Airports were shut down, delaying recovery efforts, since supplies had to be airlifted or shipped in. And the Federal Emergency Management Agency, charged with disaster relief, was already stretched thin after historic storms earlier last summer in Texas and Florida.

The result was the longest major power outage in U.S. history, and many communities on the island were left without running water for months. Toilets couldn’t flush; there was no water for showers, baths, or washing clothes. People had to rely on bottled water, but supplies were limited. Useless electric stoves had to be replaced with propane ones. Without refrigeration, food rotted and vital medicines spoiled. Only those with gas-powered generators could ward off darkness after dusk—for a few brief hours. Forget about air conditioners to relieve the sweltering heat. All the modern conveniences we take for granted were left behind.

On February 19 the power finally came back on for a neighborhood on the outskirts of Morovis, a small town in the island’s central highlands. When the lights turned on in her house, Marysol Rivera Rivas, 51, jumped up and down, hugged her neighbors, and hoisted a can of beer. “There’s the last clothes I have to wash by hand,” she exclaimed, pointing to a line of laundry flapping in the wind in her yard. “This is the first time in five months we’re able to celebrate. We’re alive now!”

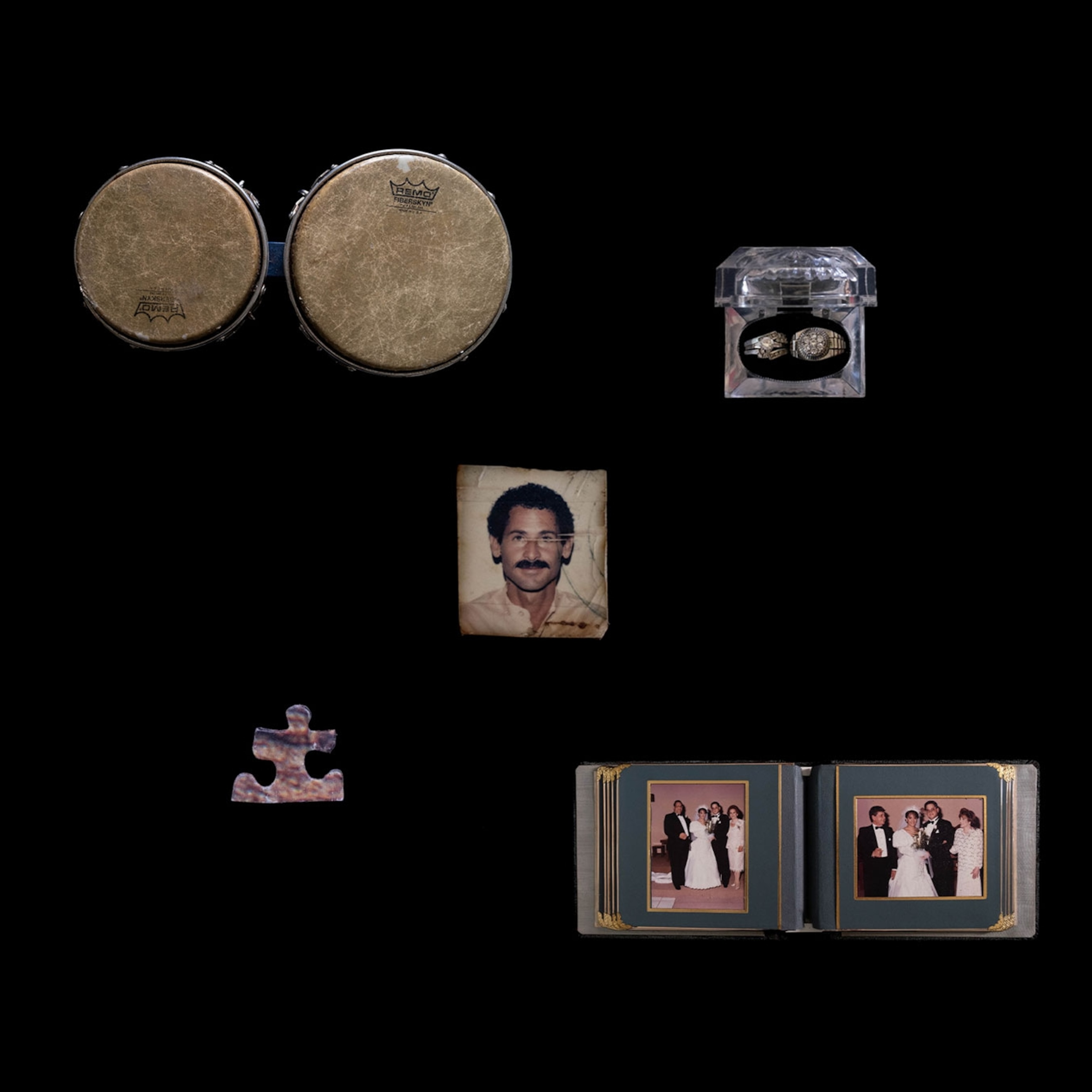

Even after power and water are restored across the island, people will still be dealing with the storm’s effects. “The storm takes away the foundations of society. Everything you thought gave you certainty is gone,” says psychologist Domingo Marqués, 39, an associate professor at Albizu University in San Juan. “You see people anxious, depressed, scared.” Marqués estimates that 30 to 50 percent of the population is experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, or anxiety.

Still, Marqués is guardedly optimistic. “We saw a lot of resiliency. We’re not going anywhere. We’re rebuilding,” he says. “We’ll be OK. But we shouldn’t try to get back to normal, because things will never be normal again.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest