See 'Underwater Snowstorm' of Coral Reproducing

Under a full moon, corals release millions of tiny eggs. Whether or not those eggs fertilize is a leap of faith.

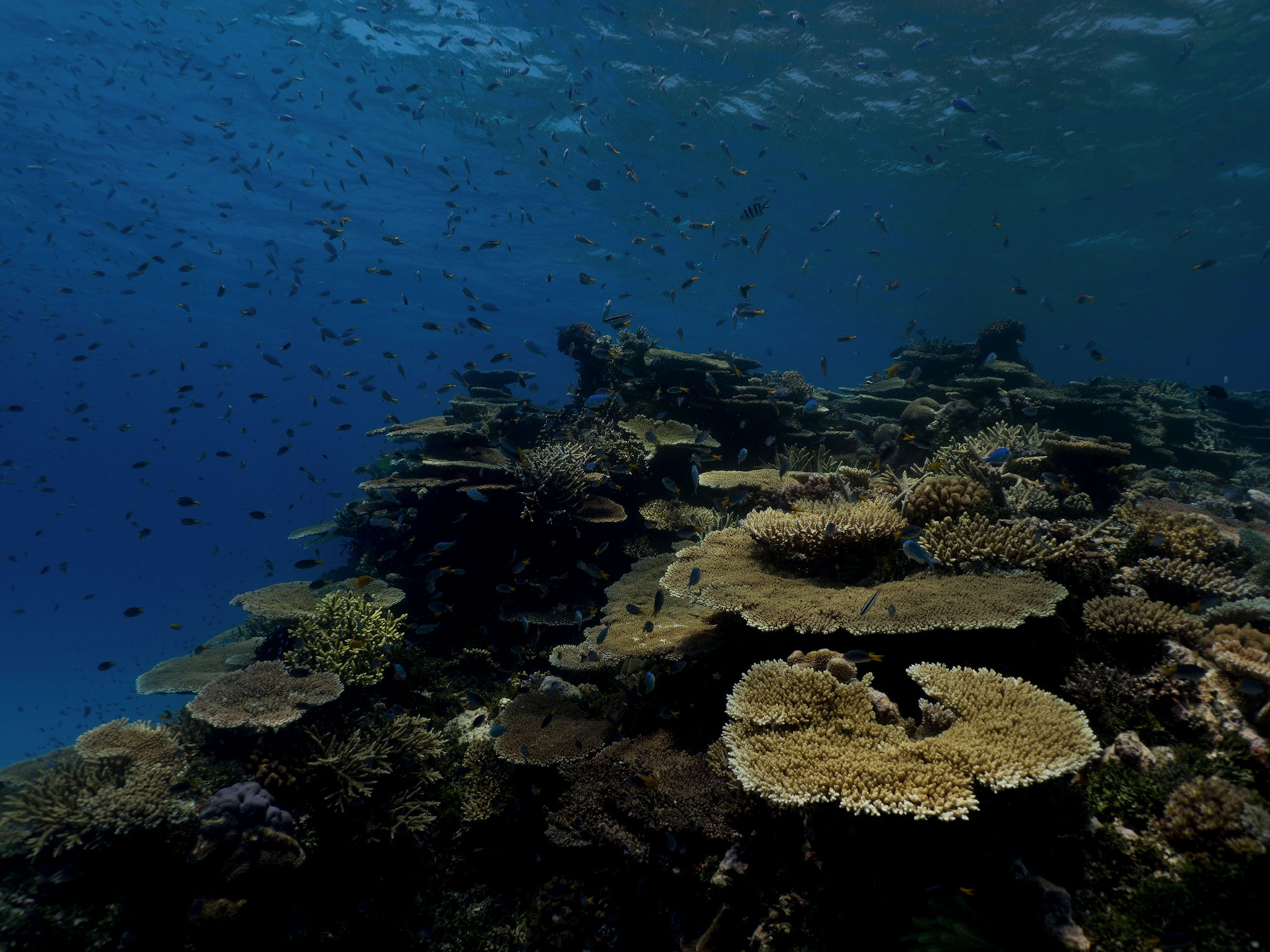

Illuminated only by a full moon, underwater photographer Michaela Skovranova and a group of divers parked in the Great Barrier Reef check the water around their boat for signs it's about to happen.

Perched on the edge of the vessel, periodically they scoop up water about every 15 minutes. In these samples, they're looking for tiny, sticky eggs recently released from the gut cavities of coral. Sometimes the eggs will produce what looks like a red slick on the water's surface.

When eggs finally turn up, it means a coral-spawning event is about to take place. When the divers see that, they quickly plunge into the water, in hopes of witnessing what can only be seen once a year, when waters are warm and the moon is full.

Hermaphroditic corals reproduce during these spawning events by releasing both male and female reproductive cells, which are called gametes. When these cells float to the water's surface, they pair up and combine. Once fertilized, the eggs develop into larvae, which eventually turn into polyps, or new coral colonies.

This process "is a leap of faith of nature," says Skovranova.

Risky Strategy

Releasing millions of these reproductive cells at the same time increases the odds that eggs will become fertilized by male gametes from other individual corals, thus ensuring genetic diversity of the offspring. Because the event happens only once a year, divers must be careful not to interfere with the process when swimming through the reef. Shining bright light on coral can prevent a spawning event from happening, but once it's in progress, the corals are unbothered by light.

To catch the spawning on camera, Skovranova dove into the darkness and tried to let her eyes adjust, instead of using a flashlight. Yet swimming through a dark reef can be risky. Much of the reef lies within enclaves where little light penetrates. Divers are careful not to injure the delicate coral or touch a crown of thorns, a large, poisonous species of starfish, that in cases of extreme allergic reactions can cause death.

During a full coral spawning, so many eggs are released at once that the event is often likened to an underwater snowstorm. But when Skovranova was diving this year, she witnessed only a split spawning, which means only some of the corals were releasing their gametes at that time. Corals that were not participating were saving their cells for a spawning event at a later date, most likely sometime in December.

Her photos of the reproductive event show how dense with eggs the waters can get, even when only some of the corals reproduce. Those eggs compete for space with a host of marine life, like zooplankton and clownfish.

Aiding Conservation

Coral spawning is a critical time of year for conservation scientists. It's during this time that coral eggs and sperm are collected to be studied and artificially grown in labs.

Artificially raised corals are becoming an increasingly important conservation tool. In 2016 and 2017, the Great Barrier Reef suffered massive coral bleaching events that damaged two thirds of the reef. Coral bleaching occurs when pollutants or abnormally warm water prompt coral to expel the algae that live symbiotically in their tissues, and which provide the polyps food through photosynthesis. When conditions don't improve, the algae don't return, and the corals eventually starve to death.

One study published by the United Nations this summer predicted all the world's corals could die off in 30 years if nothing is done to curb globally warming waters. This could have far-reaching impacts, because corals aggregate to become some of the world's largest living organisms, and they provide critical habitat to a host of marine life, from fish to invertebrates.

Scientists from the Australian Institute of Marine Science plan to study the coral cells collected during this year's spawning event to see how or if corals are adapting to warmer waters. There is some early indication that some corals are more resilient to warming than previously thought, giving some hope to conservationists.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico