Epic Picture Shows Thousands of Galaxies in One Frame

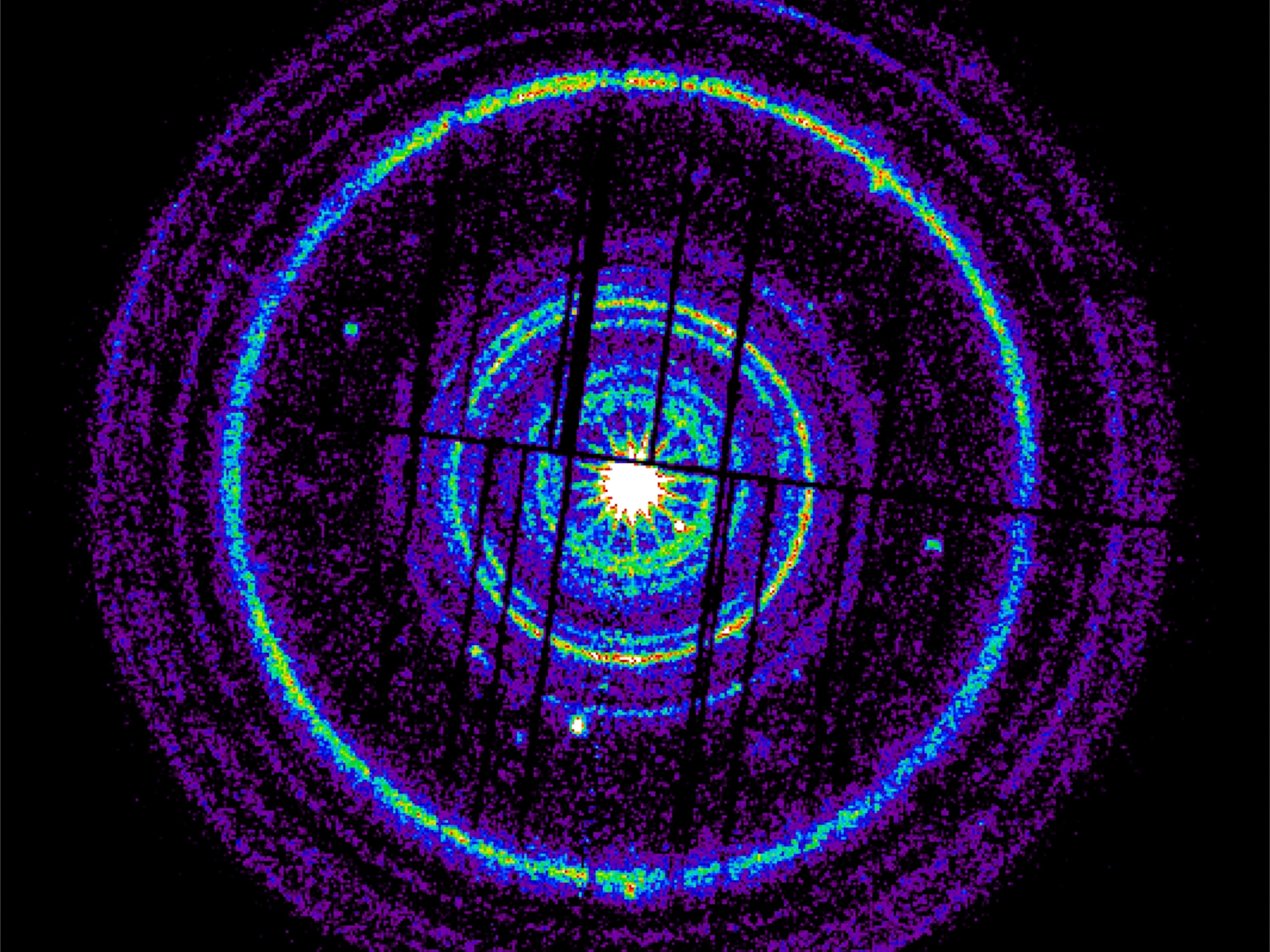

A groundbreaking telescopic portrait reveals galaxies millions of light-years away, and colors the human eye can't see.

Even on the starriest of nights, the human eye sees just a tiny fraction of the cosmos. So if the curve of the Big Dipper or the four points of the Southern Cross appear magnificent, consider how many more phenomena must exist out of view.

That prospect is what led astronomer Natasha Hurley-Walker to a radio telescope deep in the outback of Western Australia. The telescope, called the Murchison Widefield Array, is made up of thousands of antennas that see through celestial dust and detect “radio light”—revealing colors and objects in a spectrum not visible to humans, even with the aid of optical telescopes like Hubble. Stretched across nearly four square miles of desert, the antennas—cheaper to produce and maintain than typical dishes—look like “an army of mechanical spiders,” she says.

In the past four years, Hurley-Walker and a team of researchers—from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth as well as other institutions in Australia and New Zealand—have stitched together more than 40,000 images taken by the telescope.

The result is a groundbreaking portrait of the entire southern sky. It exposes hundreds of thousands of galaxies millions of light-years away. And it shows in unobscured, blazing color the radio glow of the Milky Way, lit up with the remains of exploded stars and intense magnetic fields. This sweeping survey, says Hurley-Walker, “allows people to see the sky with radio eyes.”

Her research is far from finished. Hurley-Walker is now working with an international team to develop a radio telescope many times bigger and more sensitive than the Murchison Widefield Array. Its technology could pick up fainter signals, which would unveil millions more galaxies and—if her wish comes true—“the birth of the very first stars.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest