Life Aboard the Longest Train Ride Through India

Beneath the relentless churn of steel, wood, and dust, the Indian railway is made entirely of stories.

Beneath the relentless churn of steel, wood, and dust, the Indian railway is made entirely of stories. For more than a century, it has witnessed the infinite expression of the human condition, borne the incalculable weight of separations, and gently rocked the world-weary into oblivion.

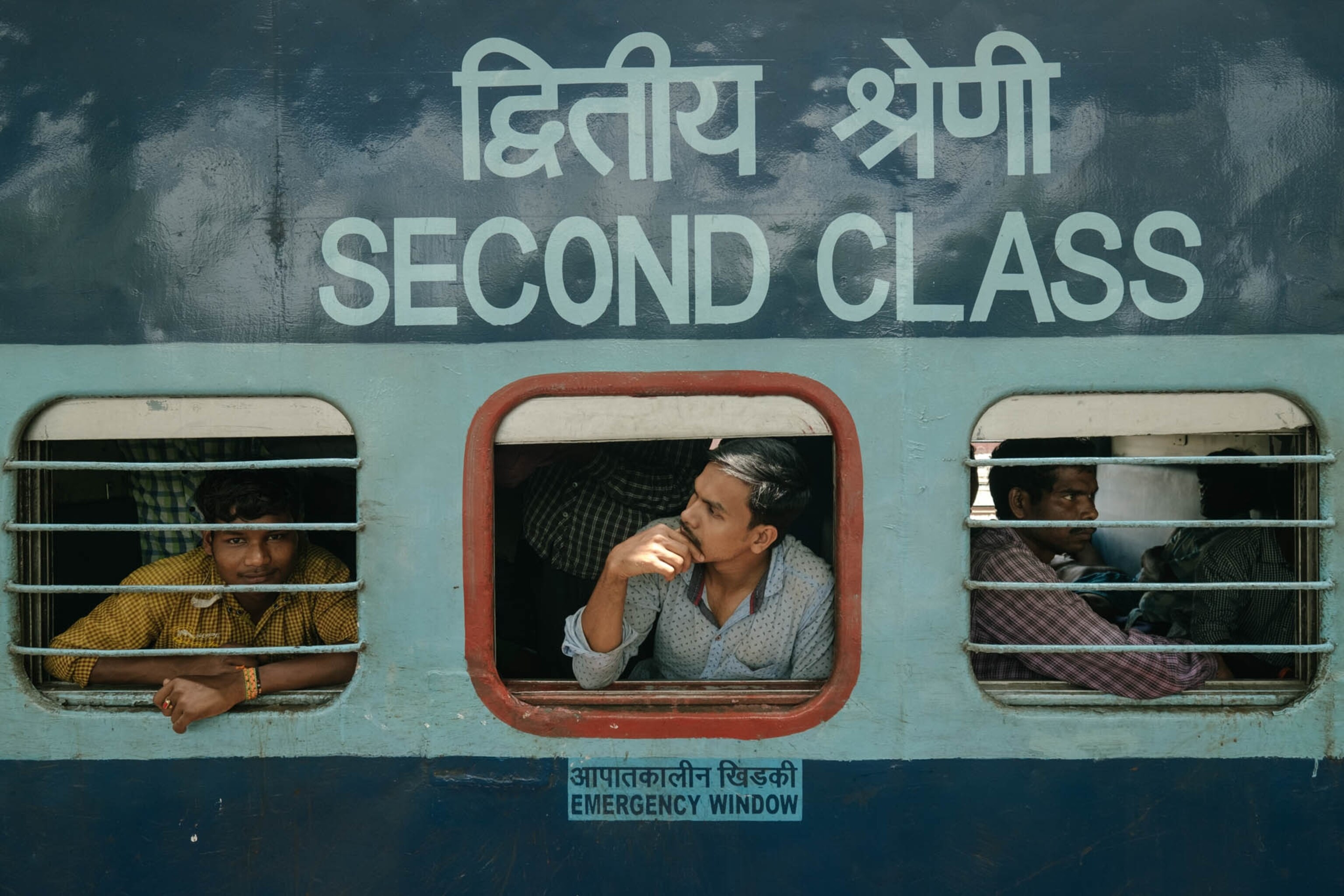

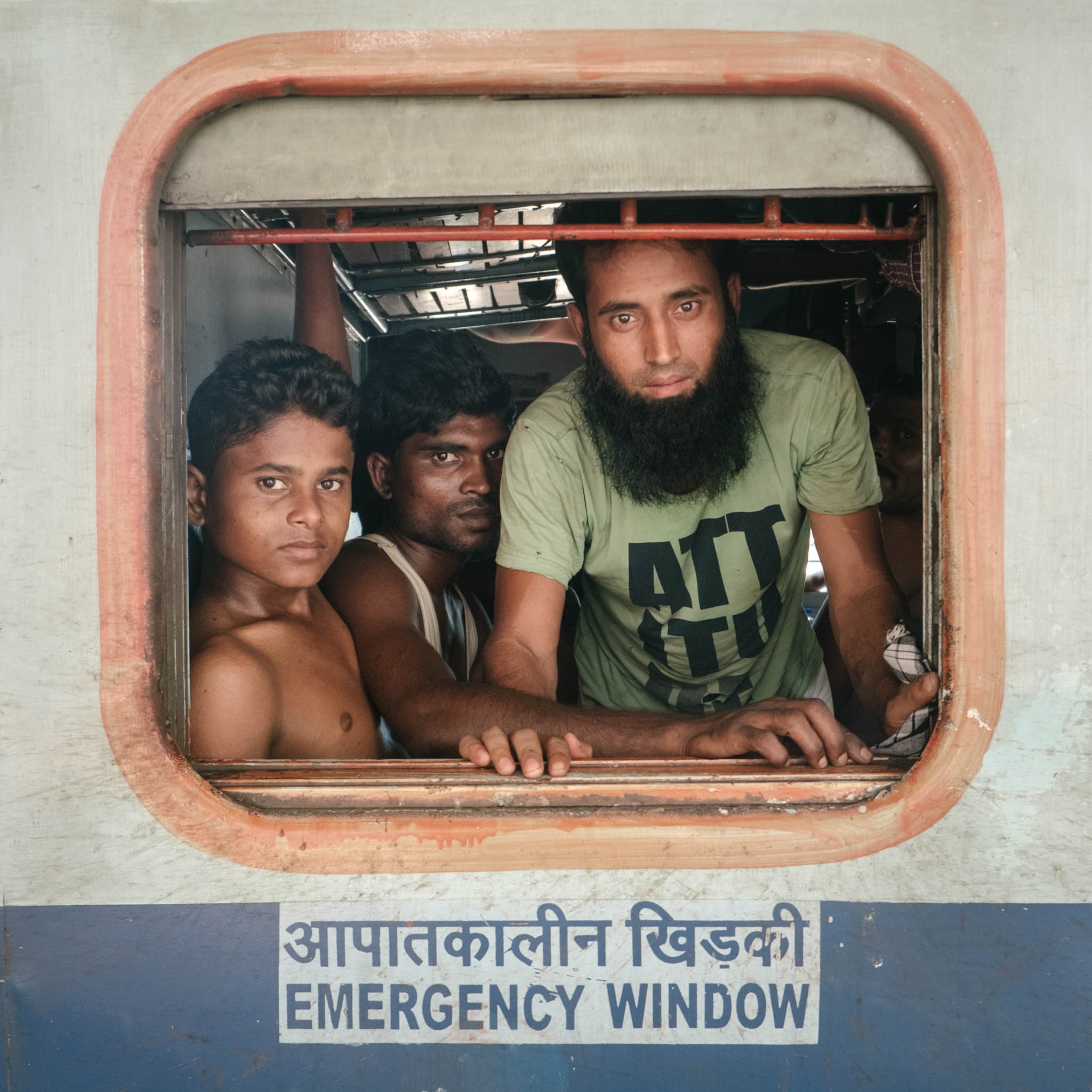

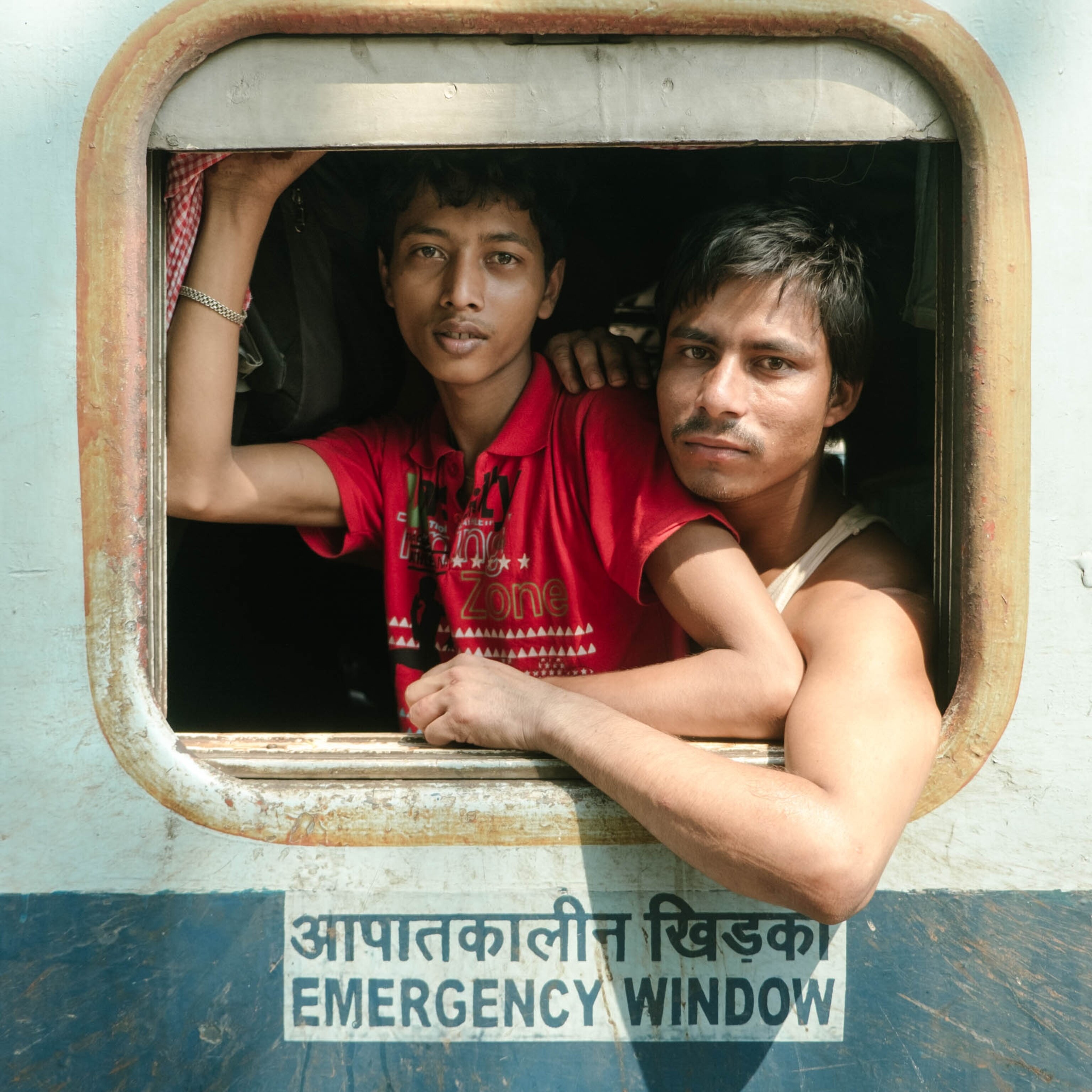

“It’s fresh and beautiful and repulsive at the same time,” says National Geographic photographer Matthieu Paley, who spent five days and four nights aboard the Vivek Express documenting its ever-unfolding story. Starting at the southernmost tip of India, the route stretches 2,637 miles northward from Kanniyakumari to Dibrugarh under the heavy gaze of the equatorial sun. It is the longest train ride in the Indian subcontinent.

“People want time,” Paley says. “We live in a world that wants to compress time and make things faster and faster, and I love the train because it’s an environment where you have to slow down.”

The “slow travel” movement can be traced back to the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, an epoch defined by unprecedented acceleration, the omnipresence of technology, and commodification of time. The Romantics warned this modern fixation on speed was a self-made “iron cage” that would lead to alienation, loss of meaning, and an unwillingness towards self-reflection. The remedy, they proposed, was deceleration.

“My favorite kind of photography happens when I slow down; but these days it’s not easy,” Paley says. “On trains, I am held hostage, disconnected, suspended in time. It forces me to slow down. This is what I crave: Give me a long, slow ride and I am happy.”

The experience of time, however, hinges entirely upon our continuously evolving perceptions of speed. While rail travel may be slow by contemporary standards, when India’s first train traversed 21 miles from Bombay to Thana in April 1853, it was a triumph of engineering and criticized for the same reasons set forth by the Romantics.

Over the next century and a half, the railway not only drastically altered Indian culture, but restructured time and space itself.

On trains, I am held hostage, disconnected, suspended in time.Matthieu Paley

Considered both a transformative technology and a symbol of British imperial oppression, the railway erased once-formidable distances, generated trade and intellectual exchange, and made travel accessible to the masses. Simultaneously, however, it fostered environments that bred infectious disease, created exploitative labor conditions, and irrevocably altered the natural landscape.

British colonists viewed the train as a harbinger of progress—a tool to abolish the caste system and forge a capitalist society. Instead, it evolved into a space that was invariably Indian: beauty and chaos in tandem.

“The Indian subcontinent can be a disturbing place,” Paley says. “There is a certain lightness of being, but it’s hard to spot at first, hidden under all the noise and ongoing colorful madness. That’s what I love about this part of the world—you can just engage with your surroundings without sounding weird.”

This unflinching engagement is fundamental to slow travel, which places value on quality of interactions with local cultures over the rapid acquisition of passport stamps. This ideal hearkens back to the Romantic belief that preoccupation with the future corrupts the present journey.

Scientists agree that industrialized societies are experiencing a paradoxical “time famine”—the persistent feeling that we have too much to do, and not enough time to accomplish it—and that this interferes with our ability to savor immaterial experiences. We’re doing everything faster, but we don’t feel like we have more free time.

As India hurtles ceaselessly into the future, it’s unclear what the next generation of train travel will look like. With the support of a 12-billion-dollar loan from Japan, the government is currently developing a high speed bullet train that will connect the cities of Mumbai and Ahmedabad. "This enterprise will launch a revolution in Indian railways and speed up India's journey into the future,” according to Prime Minster Narendra Modi. “It will become an engine of economic transformation.”

This is, perhaps, the duality of modernization—it has the potential to drastically improve lives while simultaneously engendering spiritual atrophy.

Henry David Thoreau prescribed “a tonic of wildness” to escape the voracious pace of urbanization. But in a country of 1.3 billion, wildness is a state of mind—a willingness to confront life in all its messy iterations. With more than 22 million daily passengers, 1.3 million employees, and 41,000 miles of tracks, the Indian railway teems with life.

“We are a collective mass moving along in rhythm, shaking, ever-evolving,” Paley says. “If you pay attention, you can engage with the pure joy of traveling. For me, it is the feeling of being united with all our differences.”

If you pay attention, you can engage with the pure joy of traveling. For me, it is the feeling of being united with all our differences.Matthieu Paley

Matthieu Paley's work has been featured in National Geographic magazine and news. See photos from his journey through China by train and follow him on Instagram @paleyphoto.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park