The science behind psychopaths and extreme altruists

Researchers have found that the way our brains are wired can affect how much empathy we feel toward others—a key measuring stick of good and evil.

From the kitchen window of her mobile home in Auburn, Illinois, Ashley Aldridge had a clear view of the railroad crossing about a hundred yards away.

When the 19-year-old mother first saw the man in the wheelchair, she had just finished feeding lunch to her two children, ages one and three, and had moved on to washing dishes—one more in an endless string of chores. Looking up, Aldridge noticed that the wheelchair wasn’t moving. It was stuck between the tracks. The man was yelling for help as a motorcycle and two cars went by without stopping.

Aldridge hurried out to ask a neighbor to watch her kids so she could go help. Then she heard the train horn and the clanging of the crossing gate as it came down, signaling that a train was on its way. She ran, barefoot, over a gravel path along the tracks. When she got to the man, the train was less than half a mile away, bearing down at about 80 miles an hour. Failing to dislodge the wheelchair, she wrapped her arms around the man’s chest from behind and tried to lift him, but couldn’t. As the train barreled toward them, she pulled with a mighty heave. She fell backward, yanking him out of the chair. Within seconds, the train smashed the wheelchair, carrying fragments of steel and plastic half a mile up the track.

The man Aldridge saved that afternoon in September 2015 was a complete stranger. Her unflinching determination to save him despite the threat to her own life sets her apart from many. Aldridge’s heroic rescue is an example of what scientists call extreme altruism—selfless acts to help those unrelated to oneself at the risk of grave personal harm. Not surprisingly, many of these heroes—such as Roi Klein, an Israeli army major who jumped on a live grenade to save his men—work in professions in which endangering one’s life to protect others is part of the job. But others are ordinary men and women—like Rick Best, Taliesin Namkai-Meche, and Micah Fletcher, who intervened to defend two young women, one wearing a hijab, from a man spewing anti-Muslim abuse at them on a commuter train in Portland, Oregon. All three were stabbed; only Fletcher survived.

Contrast these noble acts with the horrors that humans commit: murder, rape, kidnapping, torture. Consider the carnage perpetrated by the man who sprayed bullets from the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, in October at a country music festival. Three weeks later, officials put the casualty toll at 58 dead and 546 wounded. Or think about the chilling ruthlessness of a serial killer like Todd Kohlhepp, a real estate agent in South Carolina, who appears to have left clues about his murderous habit in bizarre online reviews for products, including a folding shovel: “Keep in car for when you have to hide the bodies.” In spite of how aberrant these horrors are, they occur often enough to remind us of a dark truth: Humans are capable of unspeakable cruelty.

Extreme altruists and psychopaths exemplify our best and worst instincts. On one end of the moral spectrum, sacrifice, generosity, and other ennobling traits that we recognize as good; on the other end, selfishness, violence, and destructive impulses that we see as evil. At the root of both types of behaviors, researchers say, is our evolutionary past. They hypothesize that humans—and many other species, to a lesser degree—evolved the desire to help one another because cooperation within large social groups was essential to survival. But because groups had to compete for resources, the willingness to maim and possibly kill opponents was also crucial. “We are the most social species on Earth, and we are also the most violent species on Earth,” says Jean Decety, a social neurologist at the University of Chicago. “We have two faces because these two faces were important to survival.”

For centuries the question of how good and evil originate and manifest in us was a matter of philosophical or religious debate. But in recent decades researchers have made significant advances toward understanding the science of what drives good and evil. Both seem to be linked to a key emotional trait: empathy, which is an intrinsic ability of the brain to experience how another person is feeling. Researchers have found that empathy is the kindling that fires compassion in our hearts, impelling us to help others in distress. Studies also have traced violent, psychopathic, and antisocial behaviors to a lack of empathy, which appears to stem from impaired neural circuits. These new insights are laying the foundation for training regimens and treatment programs that aim to enhance the brain’s empathic response.

Researchers once thought young children had no concern for the well-being of others—a logical conclusion if you’ve seen a toddler’s tantrums. But recent findings show that babies feel empathy long before their first birthday. Maayan Davidov, a psychologist at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and her colleagues have conducted some of these studies, analyzing the behavior of children as they witness somebody in distress—a crying child, an experimenter, or their own mother pretending to be hurt. Even before six months of age, many infants respond to such stimuli with facial expressions reflecting concern; some also exhibit caring gestures such as leaning forward and trying to communicate with the one in distress. In their first year, infants also show signs of trying to understand the suffering they’re seeing. Eighteen-month-olds often translate their empathy into such positive social behavior as giving a hug or a toy to comfort a hurt child.

That’s not true of all children, however. In a small minority, starting in the second year of life, researchers see what they call an “active disregard” of others. “When someone reported that someone had hurt themselves,” says Carolyn Zahn-Waxler, a researcher at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, “these children would kind of laugh at them or even kind of swipe at them and say, ‘You’re not hurt,’ or ‘You should be more careful’—saying it in a tone of voice that was judgmental.” Following these toddlers into adolescence, Zahn-Waxler and her colleague Soo Hyun Rhee, a psychologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, found they had a high likelihood of developing antisocial tendencies and getting into trouble.

Other studies have measured callousness and lack of emotional expression in adolescents using questions such as whether the subject feels remorseful upon doing something wrong. Those with high scores for “callous-unemotional” traits tend to have frequent and severe behavioral problems—showing extreme aggression in fights, for instance, or vandalizing property. Researchers have also found that some of these adolescents end up committing major crimes such as murder, rape, and violent robbery. Some are prone to becoming full-blown psychopaths as adults—individuals with cold, calculating hearts who wouldn’t flinch while perpetrating the most horrific acts imaginable. (Most psychopaths are men.)

If the empathy deficit at the core of psychopathic behaviors can be traced all the way back to toddlerhood, does evil reside in the genes, coiled up like a serpent in the DNA, waiting to strike? The answer isn’t a categorical yes or no. As it is with many illnesses, both nature and nurture have a hand. Studies of twins have established that callous-unemotional traits displayed by some young children and adolescents arise to a substantial degree from genes they inherit. Yet in a study of 561 children born to mothers with a history of antisocial behaviors, researchers found that those living with adoptive families that provided a warm and nurturing environment were far less likely to exhibit callous-unemotional traits than those with adoptive families that were not as nurturing.

Children born with genes making it more likely that they will have difficulty empathizing are often unable to get a break. “You can imagine that if you have a child who doesn’t show affection in the same way as a typically developing child, doesn’t show empathy, that child will evoke very different reactions in the people around them—the parents, the teachers, the peers—than a child who’s more amenable, more empathetic,” says Essi Viding, a research psychologist at University College London. “And many of these children, of course, reside within their biological families, so they often have this double whammy of having parents who are perhaps less well equipped for many of the parenting tasks, are less good at empathizing, less good at regulating their own emotions.”

The firefighters tried desperately to save the six Philpott children from their burning house in Derby, England, in the early hours of May 11, 2012. But the heat and smoke were so intense that only one of the kids was alive when rescuers finally made their way upstairs where they had been sleeping. That boy, too, perished two days later in the hospital. The police suspected arson, based on evidence that the fire had been started by pouring gasoline through the door’s mail slot.

Derby residents raised money to help the children’s parents—Mick and Mairead Philpott—pay for a funeral. At a news conference to thank the community, Philpott was sobbing and dabbing his eyes with a tissue that remained curiously dry. Leaving the event, he collapsed, but Derbyshire’s assistant chief constable, walking behind, was struck by the unnaturalness of the behavior. Eighteen days later, the police arrested Philpott and his wife. Investigators determined that they had set fire to the house with an accomplice to frame Mick’s mistress. A court found all three guilty of manslaughter.

Philpott’s faking of grief and his lack of remorse are among the characteristics that define psychopaths, a category of individuals who have come to embody evil in the popular imagination. Psychopaths have utter disregard for the feelings of others, although they seem to learn to mimic emotions. “They really just have a complete inability to appreciate anything like empathy or guilt or remorse,” says Kent Kiehl, a neuroscientist at the Mind Research Network and the University of New Mexico who was drawn to studying psychopathy in part because he grew up in a neighborhood that was once home to the serial killer Ted Bundy. These are people who are “just extremely different than the rest of us.”

Kiehl has spent the past two decades exploring this difference by scanning the brains of prison inmates. (Nearly one in every five adult males in prison in the U.S. and Canada scores high in psychopathy, measured using a checklist of 20 criteria such as impulsivity and lack of remorse, compared with one out of every 150 in the general male population.)

Using an MRI scanner installed inside a tractor trailer, Kiehl and his colleagues have imaged more than 4,000 prison inmates since 2007, measuring the activity in their brains as well as the size of different brain regions.

Psychopathic criminals show reduced activity in their brain’s amygdala, a primary site of emotional processing, compared with non-psychopathic inmates when recalling emotionally charged words they were shown moments earlier, such as “misery” and “frown.” In a task designed to test moral decision-making, researchers ask inmates to rate the offensiveness of pictures flashed on a screen, such as a cross burning by the Ku Klux Klan or a face bloodied by a beating. Although the ratings by psychopathic offenders aren’t that different from those by non-psychopaths—they both recognize the moral violation in the pictures—psychopaths tend to show weaker activation in brain regions instrumental in moral reasoning.

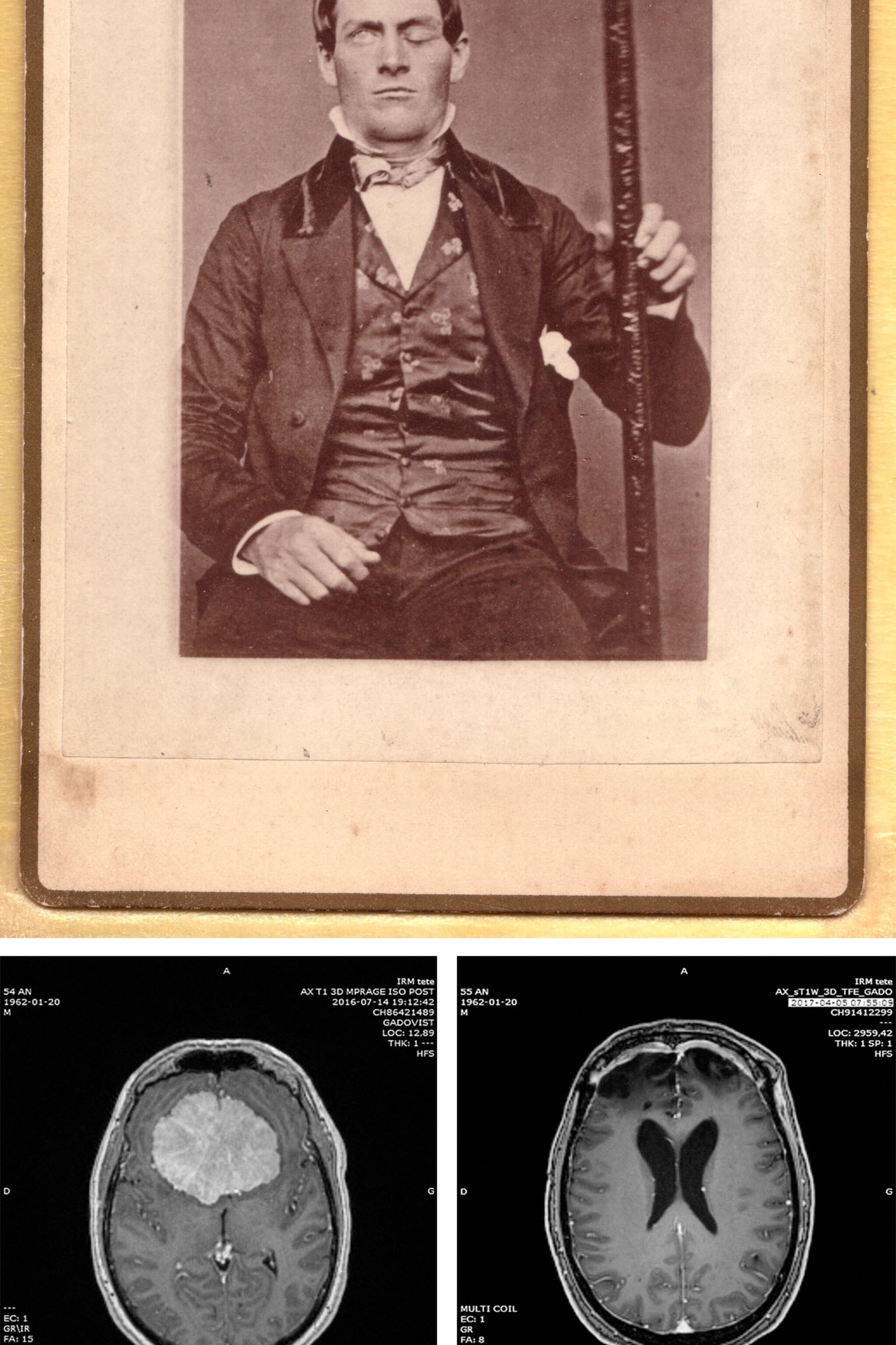

Based on these and other, similar findings, Kiehl is convinced that psychopaths have impairments in a system of interconnected brain structures—including the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex—that help process emotions, make decisions, control impulses, and set goals. There is “basically about 5 to 7 percent less gray matter in those structures in individuals with high psychopathic traits compared to other inmates,” Kiehl says. The psychopath appears to compensate for this deficiency by using other parts of the brain to cognitively simulate what really belongs in the realm of emotion. “That is, the psychopath must think about right and wrong while the rest of us feel it,” Kiehl wrote in a paper he co-authored in 2011.

When Abigail Marsh, a psychologist at Georgetown University, was 19, her car skidded on a bridge after she swerved to avoid hitting a dog. The vehicle spun out of control and finally came to a stop in the fast lane, facing oncoming traffic. Marsh couldn’t get the engine to start and was too afraid to get out, with cars and trucks rushing past the vehicle. A man pulled over, ran across the highway, and helped start the car. “He took an enormous risk running across the freeway. There’s no possible explanation for it other than he just wanted to help,” Marsh says. “How can anybody be moved to do something like that?”

Marsh kept turning that question over in her head. Not long after she began working at Georgetown, she wondered if the altruism shown by the driver on the bridge wasn’t in some ways the polar opposite of psychopathy. She began looking for a group of exceptionally kind individuals to study and decided that altruistic kidney donors would make ideal subjects. These are people who’ve chosen to donate a kidney to a stranger, sometimes even incurring financial costs, yet receive no compensation in return.

Marsh and her colleagues brought 19 donors in from around the country for the study. The researchers showed each one a series of black-and-white photographs of facial expressions, some fearful, some angry, and others neutral, while their brains were scanned using an MRI machine to map both activity and structure.

When looking at fearful faces, donors showed a greater response in their right amygdala than a control group. Separately, the researchers found that their right amygdalas were, on average, 8 percent larger than those of the control group. Similar studies done previously on psychopathic subjects had found the opposite: The amygdalas in psychopathic brains are smaller and activated less than those in controls while reacting to frightened faces.

“Fearful expressions elicit concern and caring. If you’re not responsive to that expression, you’re unlikely to experience concern for other people,” Marsh explains. “And altruistic kidney donors just seem to be very sensitive to other people’s distress, with fear being the most acute kind of distress—maybe in part because their amygdalas are larger than average.”

The majority of people in the world are neither extreme altruists nor psychopaths, and most individuals in any society do not ordinarily commit violent acts against one another. And yet, there are genocides—organized mass killings that require the complicity and passivity of large numbers of people. Time and again, social groups organized along ethnic, national, racial, and religious lines have savaged other groups. Nazi Germany’s gas chambers extinguished millions of Jews, the Communist Khmer Rouge slaughtered fellow Cambodians in the killing fields, Hutu extremists in Rwanda wielding machetes slaughtered several hundred thousand Tutsis and moderate Hutus, and Islamic State terrorists massacred Iraq’s Yazidis—virtually every part of the world appears to have suffered through a genocide. Events such as these provide ghastly evidence that evil can hold entire communities in its grip.

How the voice of conscience is rendered inconsequential to foot soldiers of a genocide can be partly understood through the prism of the well-known experiments conducted in the 1960s by the psychologist Stanley Milgram at Yale University. In those studies, subjects were asked to deliver electric shocks to a person in another room for failing to answer questions correctly, increasing the voltage with every wrong answer. At the prodding of a person in a lab coat who played the role of an experimenter, the subjects often dialed up the shocks to dangerously high voltage levels. The shocks weren’t real and the cries of pain heard by the subjects were prerecorded, but the subjects only found that out afterward. The studies demonstrated what Milgram described as “the extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority.”

Gregory Stanton, a former U.S. State Department official and founder of Genocide Watch, a nonprofit that works to prevent mass murder, has identified the stages that can cause otherwise decent people to commit murder. It starts when demagogic leaders define a target group as “the other” and claim it is a threat to the interests of supporters. Discrimination follows, and soon the leaders characterize their targets as subhuman, eroding the in-group’s empathy for “the other.”

Next, society becomes polarized. “Those planning the genocide say, ‘You are either with us or against us,’ ” says Stanton. This is followed by a phase of preparation, with the architects of the genocide drawing up death lists, stocking weapons, and planning how the rank and file are to execute the killings. Members of the out-group are sometimes forced to move into ghettos or concentration camps. Then the massacres begin.

Many of the perpetrators remain untouched by remorse, not because they are incapable of feeling it—as is the case with psychopathic killers—but because they find ways to rationalize the killings. James Waller, a genocide scholar at Keene State College in New Hampshire, says he got a glimpse of this “incredible capacity of the human mind to make sense of and to justify the worst of actions” when he interviewed dozens of Hutu men convicted or accused of committing atrocities during the Rwandan genocide. Some of them had hacked children, even those they personally knew, to death. Their rationale, according to Waller, was: “If I didn’t do this, those children would have grown up to come back to kill me. This was something that was a necessity for my people to be safe, for my people to survive.”

Our capacity to empathize and channel that into compassion may be innate, but it is not immutable. Neither is the tendency to develop psychopathic and antisocial personalities so fixed in childhood as to be unchangeable. In recent years researchers have shown the feasibility of nipping evil in the bud as well as strengthening our positive social instincts.

The possibility of preventing violent teenage boys from hardening into lifelong criminals has been put to the test at the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center in Wisconsin, a facility that houses serious offenders but is run more as a psychiatric unit than as a prison. The adolescents referred to the center come in with already long criminal histories—teenagers who are a threat to others. “These are folks who essentially have dropped out of the human race—they don’t have any connection to anyone, and they are in a real antagonistic posture with everybody,” says Michael Caldwell, a senior staff psychologist.

The center attempts to build a connection with the kids despite their aggressive and antisocial behaviors. Even when an inmate hurls feces or sprays urine at staff members—a common occurrence at many correctional institutions—the staff members keep treating the offender humanely. The kids are scored on a set of behavior rating scales every day. If they do well, they earn certain privileges the following day, such as a chance to play video games. If they score badly, say, by getting into a fight, they lose privileges. The focus is not on punishing bad behavior but on rewarding good conduct. That’s different from most correctional institutions. Over time the kids start to behave better, says Greg Van Rybroek, the center’s director. Their callous-unemotional traits diminish. Their improved ability to manage their emotions and control their violent impulses seems to endure beyond the walls of Mendota. Adolescents treated in the program have committed far fewer and less violent offenses between two and six years after release than those treated elsewhere, the center’s studies have found. “We don’t have any magic,” Van Rybroek says, “but we’ve actually created a system that considers the world from the youth’s point of view and tries to break it down in a fair and consistent manner.”

During the past decade researchers have discovered that our social brain is plastic, even in adulthood, and that we can be trained to be more kind and generous. Tania Singer, a social neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, has pioneered studies demonstrating this.

Empathy and compassion use different networks in the brain, Singer and her colleagues found. Both can lead to positive social behavior, but the brain’s empathic response to seeing another person suffer can sometimes lead to empathic distress—a negative reaction that makes the onlooker want to turn away from the sufferer to preserve his or her own sense of well-being.

To enhance compassion, which combines awareness of another’s distress with the desire to alleviate it, Singer and her colleagues have tested the effects of various training exercises. A prominent exercise, derived from Buddhist traditions, involves having subjects meditate on a loved one—a parent or a child, for example—directing warmth and kindness toward that individual and gradually extending those same feelings toward acquaintances, strangers, and even enemies, in an ever widening circle of love. Singer’s group has shown that subjects who trained in this form of loving-kindness meditation even for a few days had a more compassionate response—as measured by the activation of certain brain circuits—than untrained subjects, when watching short film clips of people suffering emotional distress.

In another study, Singer and her colleagues tested the effects of compassion training on helpfulness by using a computer game in which subjects guide a virtual character on a computer screen through a maze to a treasure chest, opening gates along the way. They can also choose to open gates for another character wandering about, looking for treasure. The researchers found that subjects who underwent compassion training were more helpful than those in a control group toward the other character—the equivalent of a stranger.

That we might be able to mold our brains to be more altruistic is an ennobling prospect for society. One way to bring that future closer, Singer believes, would be to include compassion training in schools. The result could be a more benevolent world, populated by people like Ashley Aldridge, in which reflexive kindness loses its extraordinariness and becomes a defining trait of humanity.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park