A Struggle for Identity in a Forgotten Corner of Europe

Amid the ghosts of the past empires, residents of Gagauzia fight poverty and a loss of tradition to maintain their culture.

The question of independence has hung over the Moldovan region of Gagauzia for decades. Though its people are desperately poor and rely on agriculture to survive, they cherish their language and culture deeply. Their lives are governed by the land but their hearts are governed by a yearning for identity.

For photographer Julien Pebrel, who has been documenting Gagauzia for three months, it was the mystery behind this unresolved question of independence that first drew him in. “I simply heard the word ‘Gagauzia’, which sounds very intriguing to me, [along with the words] ‘autonomous’, ‘split territory’ and ‘shepherds’ and it was enough to give me a haunting will to go there,” Pebrel tells National Geographic.

The little-known region is small, with just three towns and a population of 160,000, and was formed out of a 19th century rivalry between the Ottoman and Russian empires. The flat, bucolic landscape comes alive in spring and summer but in winter, the people retreat into hibernation. Pebrel witnessed how drastically the arc and rhythm of their lives changed as the seasons drifted. “It is a harsh winter,” he says. “It gets down to minus 10 or 15 degrees-celsius. Nobody is on the streets. They stay at home and wait for spring to arrive so they can start working in the fields again.”

Pebrel’s intention for the project was to try and understand the Gagauzian identity. The Gagauz are a unique blend of ethnically Turkic and Christian Orthodox, though religion is “not their driving force”. Their food has traces of Turkish influence and there are hints of Balkan style in the way they dress but it is their language - which originates from the Oghuz branch of the Turkic family - that is the remaining, distinguishing ingredient. To this day, very few Gagauzs speak Moldovan, choosing instead to speak Gagauzian or Russian.

To Pebrel, it seemed Gagauz traditions had strong meaning in the past but “the old songs that women proudly sang are no longer sung, the traditional clothes are only used in folkloric festivals and the traditional ceremonies have disappeared”. The culture that was once proudly worn appears to have been discarded by the younger generation and may soon be forgotten entirely.

This keen sense of tradition bleeds into a contradictory sense of history. The 1946-47 Moldovan famine, one of the least known episodes of state terror under Stalin, killed approximately 123,000 people but seems to have done little to tarnish relations. Pebrel met and photographed some Gagauz survivors, one of whom was saved from near-death by his aunt. “I met two survivors and they suffered a lot,” he says. “But when you ask about ties to Russia they say, ‘Aw well they are our protectors and our friends’. It's a selective memory.”

As Moldova edges closer to EU integration, Gagauzia continues to seek shelter from its friends, Russia and Turkey. And though autonomy was granted to the region in 1994, the Gagauz are “satisfied in theory but not in practice.” “There is a feeling that their economy is totally destroyed and is worse than in Moldova,” he says. “All of them will tell you that their autonomy is not respected and that they should have more power to develop themselves.”

Weak economic prospects mean agriculture is their sustenance. “In the morning they have to take the sheep up to the fields. Then they come back to take care of the chickens and tend to their garden for the vegetables and fruit,” Pebrel explains. “Then they milk the cows; they make their own butter, milk and cheese.” A pastoral fantasy on paper perhaps, but for the Gagauz, the reality is relentless hardship and grinding poverty. “They don’t enjoy it,” says Pebrel. “The younger generation don't want to live this kind of life so they go to work abroad.”

The disparate values of young and old make the future of Gagauzian autonomy uncertain. “The older generation have a language and a culture they identify with,” says Pebrel. “But they say, 'Well we have autonomy but the younger generation can't speak the Gagauzian language, they only speak Russian.”

Houses of Culture – a relic from the Soviet era – are dotted around the region, hosting arts, theater and music classes in an attempt to insight some adolescent interest in what it means to be Gagauz. But the allure of modern life proves irresistible to most. “If the younger generation continue to go and work in Russia and Turkey,” says Pebrel. “I think the culture will eventually disappear.”

Julien Pebrel is a photographer based in Paris and is represented by M.Y.O.P. Agency. See more of his work here and follow him on Instagram. This project was done in collaboration with journalist Anaïs Coignac.

Follow Alexandra Genova on Twitter @alexandraaa_cg

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

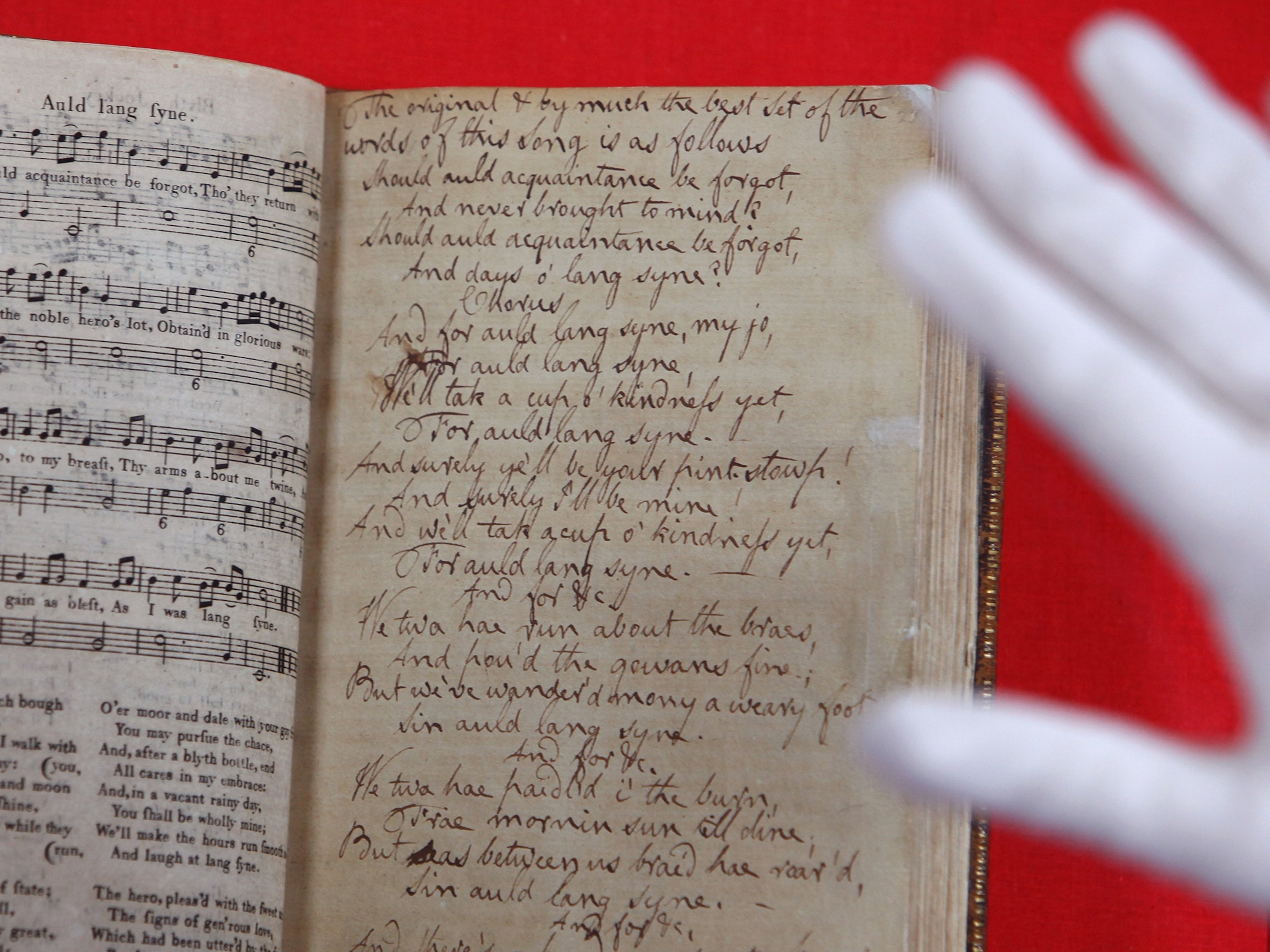

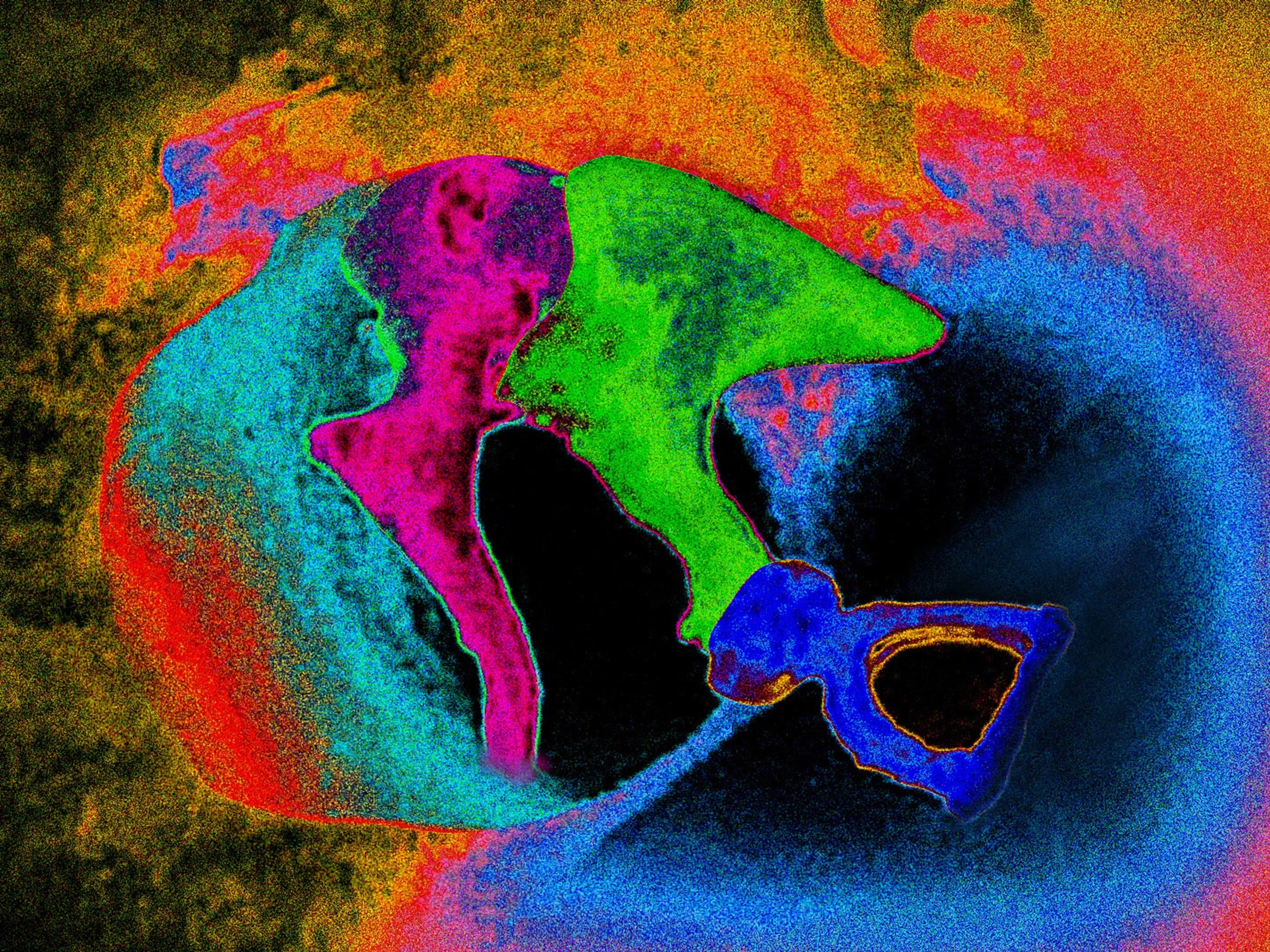

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads