What vaccines mean for the return of travel

COVID-19 jabs will eventually help tourism start again, but expect a trip full of immunity passports, mouthwash tests, and wary travelers.

At the end of December 2020, hope returned to the world, including hope for restarting travel, as countries began approving the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines. Sometime in 2021, when enough people are vaccinated against—and immune from—COVID-19, this could mean a return to globetrotting (or at least less-risky domestic vacations).

Yet anxiety surrounding travel isn’t going away as medical workers and older Americans begin to get jabbed. In the United States, people are still reluctant to plan future trips. A December 2020 National Geographic and Morning Consult poll asked how respondents would approach travel after the coronavirus pandemic was under control. Forty-nine percent said they would “travel less due to concern of exposure to other people” and a third (34 percent) said they didn’t expect to travel more in 2021 to make up for the lack of trips in 2020.

What do COVID-19 vaccines mean for travel in the near and short term, and how will attitudes toward them speed up (or slow down) the process of getting back on the road or into the skies? Here’s what we’ve learned.

There’s no vaccination for fear

“Vaccine hesitancy is a critical obstacle to overcome,” says Dr. Tom Kenyon, the chief health officer of Project HOPE, a global health and humanitarian relief organization, and a former director at U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). To get back to travel, the U.S. and the world need herd immunity, thought to be achieved when about 70 percent of the population has protective antibodies. Kenyon says, though, that “70 percent is an arbitrary figure, and there is no ‘off/on’ switch with herd immunity.” Recent news about more transmissible strains of COVID-19 suggests that herd immunity might only come when 90 percent of citizens have antibodies.

“In order to bring COVID-19 under control, a vast majority of Americans (upwards of 75 to 80 percent) will need to get vaccinated,” says Michelle Williams, epidemiologist and dean of faculty at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. But vaccine rollout is already taking longer than expected—only about three million of the promised 20 million doses were injected into American arms in December. The U.K. says it might take a year to vaccinate its population.

Every country needs herd immunity for travel to resume the way it did pre-pandemic. “We are part of a global community whose health, economy, and futures are linked and impacted by the pandemic,” says Dr. Jewel Mullen, associate dean for health equity and associate professor of population health and internal medicine at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School.

It may be tough to reach that herd stage in the U.S., though. Just 47 percent of people who responded to the National Geographic and Morning Consult poll said they’d get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it was available, and more than a quarter (27 percent) disagreed with that statement. Still, 58 percent of respondents said they would eventually get a vaccine.

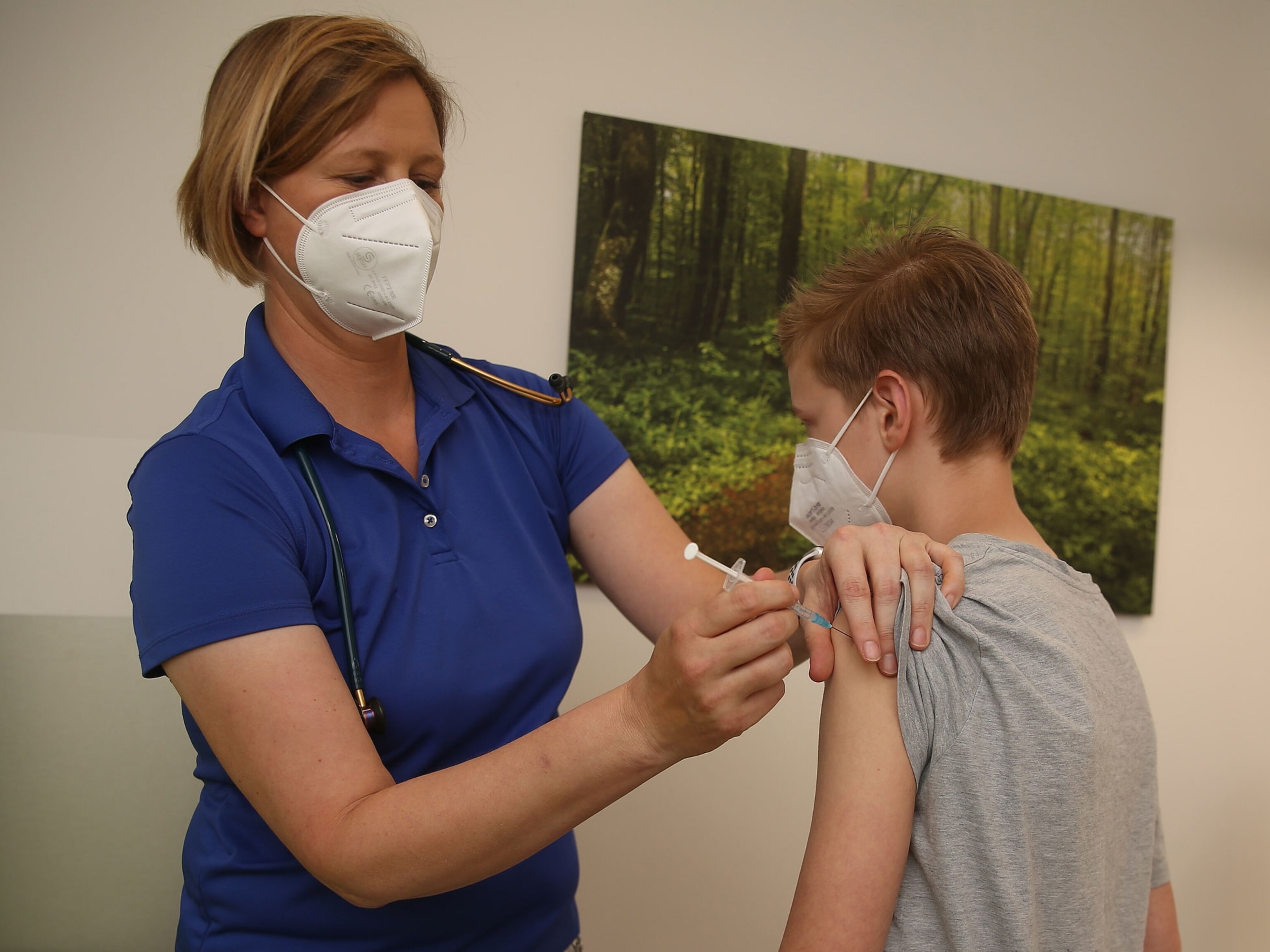

Sleeves rolled up, masks on

The new COVID vaccines are better than predicted at preventing vaccinated people from getting sick. Health experts were hoping for a vaccine with 50 to 70 percent efficacy. Clinical trials show Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine—approved now in dozens of countries including the U.S.—is a whopping 95 percent effective. It’s fully effective a month after the first dose (you need a second jab at least 21 days later) and it starts to work 10 to 12 days after the first shot. The Moderna vaccine is similar.

However, it’s still not clear if vaccinated people can spread COVID-19. “We don’t yet have data on whether any COVID vaccines reduce risk of spread/transmission; right now data only shows that vaccines reduce risk of illness,” says ABC News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jennifer Ashton.

The virus that causes COVID-19 is a novel one and there’s still a lot to learn about it. The CDC says more than half of all COVID-19 infections are spread by asymptomatic people; 35 percent before the infected person feels any symptoms and 24 percent by people who never develop symptoms. Kenyon says that “leaves open the possibility that some vaccinated people could still get infected without developing symptoms, and could then silently transmit the virus.”

Everyone wants to go on vacation again, but the priority for vaccine developers was preventing illness and death, not restarting cruises. “Trials thus far have only tracked how many vaccinated people became sick with COVID-19 compared with unvaccinated people,” says Kenyon. While there’s a good chance the antibodies triggered by the vaccine will result in a lowered likelihood of spreading the virus to others, we won’t know until more studies are done.

That’s the key reason why, a month after getting your first shot, you can’t just shop in a crowded Moroccan souk like it’s 2019. Until research tells us more, Mullen says “travelers must not abandon the measures we already know help reduce the risk of transmission—masks, good hygiene, physical distancing, and not traveling if one has symptoms.”

It’s reassuring that the majority of Americans in the National Geographic and Morning Consult poll (67 percent) plan to continue to always or sometimes wear masks during flu season, when running errands and grocery shopping (63 percent), and if there’s bad air pollution (64 percent).

The world needs immunity

Getting the world immunized won’t be quick or easy. According to the People’s Vaccine Alliance—a movement of health and humanitarian organizations including Amnesty International and Oxfam—rich countries secured 54 percent of the most promising vaccine candidates, even though they have only 14 percent of the world’s population. Without urgent action, the People’s Vaccine Alliance says that only 10 percent of the populations of 67 developing countries can be vaccinated in 2021. That puts citizens of popular tourism destinations like Cambodia, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Uganda at risk.

Rich nations securing vaccine contracts was an important part of funding vaccine development. The Vaccine Alliance accused rich nations of hoarding vaccines, and some might. Over the coming months, we’ll learn how equitable global vaccine distribution really is. Canada secured more potential vaccines than any other country—about 10 doses per person from seven vaccine candidates—and intends to share extra doses of what’s proven safe and effective. Developing countries are anxious to know how and when.

A key solution is the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator initiative and its COVAX vaccines project, co-led by the World Health Organization and other partners. COVAX’s aim is to accelerate vaccine creation and ensure equitable global distribution, first delivering enough doses for the most vulnerable 20 percent of 184 participating countries’ populations, from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Rich countries help fund poorer countries, although Russia and the U.S. have yet to join. The ACT Accelerator initiative is still underfunded, needing at least $23.7 billion in 2021.

Until the world has herd immunity, travel needs to be approached cautiously: As Mullen says, “being overly, or prematurely, confident about the vaccines’ effectiveness can lead to putting people in other countries at risk. Travel gives us a chance to contribute to their faltering economies. But contributing to disease spread undermines that.”

What’s a vaccine passport?

After the most vulnerable get their life-saving shots, eventually we’ll have enough to start inoculating the general population. That’s when vaccination status will matter. It’s unlikely you’ll need to be vaccinated to travel, but it will be a lot easier if you are.

Qantas was the first airline to announce it will require international passengers to be vaccinated. Cyprus, as of March 1, 2021, plans to allow anyone who can prove they’ve been vaccinated to skip the requirement for a negative test. Singapore is considering relaxing its quarantine rules for vaccinated travelers if clinical trials show vaccines lower transmission risks.

Even at home, being vaccinated will save you time and money: Live Nation/TicketMaster is exploring how to verify that people attending its events are either vaccinated or have a recent negative COVID test, which local authorities may require. Tourist attractions, stores, and restaurants could follow suit.

(If you must travel now, here’s how to make it safer.)

Until vaccines are readily available, COVID-19 tests will remain a necessary part of travel. However, testing is getting easier and more accurate—for example, there’s a new test (supposedly 99 percent accurate) that uses a mouthwash-like swish, not a nose swab.

How you’ll prove your vaccination status is still being figured out. Fake COVID test documents are already a problem, as is assurance that the person who took the test is the same one brandishing the certificate.

Several “vaccine passports” are being marketed, but CommonPass looks the most promising. A collaboration between the World Economic Forum and nonprofit The Commons Project, CommonPass is a secure way to validate individuals’ COVID test and vaccination credentials and is being piloted internationally. The first government to sign on to the CommonTrust Network was Aruba, allowing travelers to securely prove their COVID status to enjoy its Caribbean beaches by February 2021.

Vaccine tourism won’t be a thing—yet

COVID-19 vaccines are one of the world’s hottest commodities, which means people with money or status will try to jump the queue. Most nations say their vulnerable citizens—essential workers and the elderly—will get it first, but politicians were among the first to roll up their sleeves in the U.S., and the rich are offering donations in hopes of skipping the line.

Until there’s an abundance of approved and delivered vaccines, it’s all but impossible for anyone outside government-identified priority groups to get a shot. Yet, as soon as the U.K. approved the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, travel agents in India started fielding requests for quick vaccination trips to the U.K., even though that would require a complex web of dual citizenship, quarantines, and more. Attention is now on the U.S. and Russia as possible vaccine destinations.

Mark Warner, a trade lawyer and principal of MAAW Law in Toronto, says that, before booking a vaccination vacation, you should ask yourself how can you be certain you’re “reliably being injected with the advertised approved vaccine” versus a counterfeit. Also ponder how you can “be certain that the chain of custody has been reliably maintained at all stages,” including that proper temperatures were maintained. On top of that, will your vaccination certification be valid?

No one is safe until everyone is safe

“This is not about me, it’s about we,” says Ashton. “This pandemic has unroofed a dichotomy between responsible behavior for our own personal health and that for others’ personal health.” COVID-19 has reminded us that we live in a shared world—for all of us to be healthy and prosperous, we need to take care of each other.

Safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines mean that life, including travel, are likely to get back to normal one day. Assuming that vaccines also protect against most virus mutations as well as against spreading the virus, COVID restrictions should end once herd immunity is achieved. The whole world needs that herd immunity, and achieving that in 2021 is unlikely. Until then, reminds Mullen, “the privilege to travel somewhere should not come at the expense of the residents of those destinations.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico