How Canada's Most Endangered Mammal Was Saved

The Vancouver Island marmot once plummeted to a wild population below 30. But a band of devoted conservationists brought it back.

Fifteen years ago, a group of researchers returned from their annual field survey of Vancouver Island marmots with dire news: They had only been able to locate 22 animals. The entire wild population of this species was smaller than a kindergarten class. Conservationists estimated that within a year, it would go extinct in the wild.

The bad news got worse. The marmots weren’t breeding well in captivity, and the first attempt to release captive-bred marmots failed. These captive creatures weren’t entering hibernation, which is apparently necessary for them to breed. And three of the four released marmots were killed by cougars.

“It just seemed like blow after blow after blow for the population,” recalls Malcolm McAdie, veterinarian and captive breeding coordinator for the Marmot Recovery Foundation, which works to save the animals. “I sort of described it as having your heart pulled out slowly.” (Related: See efforts to save the quoll, a cat-sized Australian marsupial.)

Extinction seemed inevitable, says Adam Taylor, the group’s executive director. But instead of giving up, they redoubled their efforts.

Tough Teddy Bears

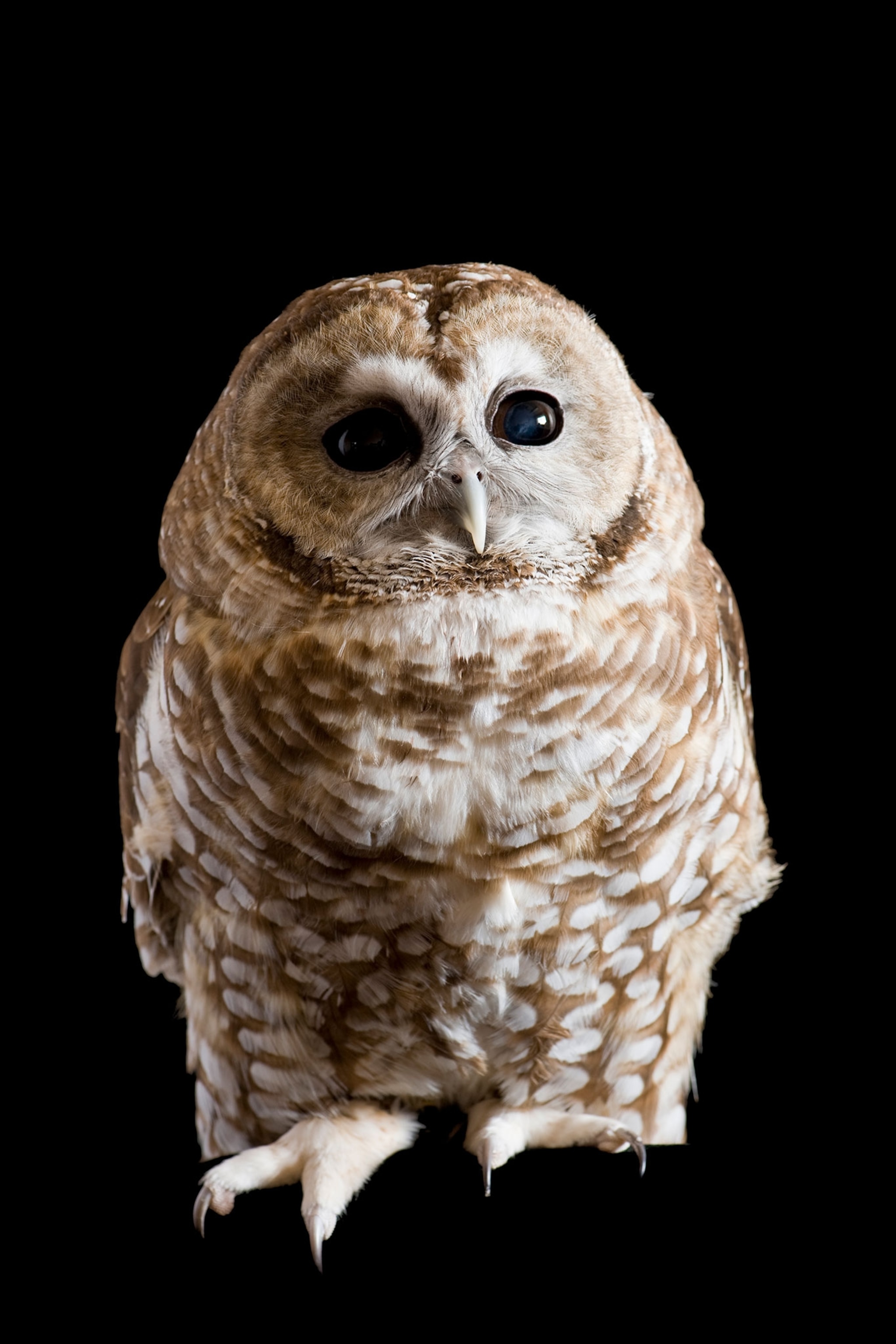

And it’s easy to see why—besides being an important part of area’s ecology, the animals are, well, adorable. “They really do look like just the most absurd creatures to survive in the wild,” Taylor says, like “living teddy bears.”

The Vancouver Island marmot (Marmota vancouverensis) is actually an oversized squirrel the size of a large house cat that is found only on this isle in British Columbia. Unlike its more common cousin the hoary marmot, which has a silvery pelage, the Vancouver Island locals sport a chocolate-brown coat, interrupted by white around their snouts and chests. (Quiz: How many endangered species can you recognize?)

The species hibernates for five to seven months of the year and emerges in spring to breed and forage in the subalpine meadows, fattening up on colorful flowers that erupt in this harsh mountainside habitat. The marmots greet parents and mates by touching noses, and the young frolic with their littermates in play.

But these are also tough creatures, making their home in the steepest avalanche chutes of the island’s mountains, strewn with precariously balanced boulders on talus slopes — sites that can be reached only by hours-long drives down remote logging roads, followed by intense ascents on foot.

Exactly how many marmots historically existed on the landscape is unknown. The first inventory, done in the 1980s, returned an estimate of 300 to 350 marmots. Through the ‘90s their numbers began to plummet, a likely result of shifts in predation patterns by wolves, golden eagles, and cougars coupled with their ill-fated colonization of clear-cuts left behind by industrial logging.

These tracts of clear-cut forest initially resembled the open, sub-alpine meadows that marmots call home, but years after the marmots moved into what resembled great habitat, the trees would grow back and provide the cover that predators needed to slaughter them.

Marmot Recovery

Following the population nadir of 2003, the Marmot Recovery Foundation resorted to several drastic measures to save the rodents.

For one, they organized a field crew to create a human shield, watching over the last of the marmots 24/7 to prevent them from being eaten by predators.

They also tweaked their efforts to captively breed the animals and reintroduce them to the wild. It was counterintuitive, especially with such a rare species, but the marmots essentially had to be starved in order to trigger hibernation, and if a male and female hibernated together, they would often produce offspring. (Related: "Marmots a “Wakeup Call” for Sex-Changing Chemicals.")

"We spend a lot of our time essentially playing the dating game with marmots,” says Taylor. “We try and find a suitable mate that’s unpaired, and often they’ll settle down together.”

Once marmots paired up and bred in captivity, getting them to survive in the wild was another matter. At first, the results were abysmal. Now, instead of introducing marmots straight to the wild, they do a phased in re-introduction whereby the captive-born marmots spend a year with the wild marmot colony on Mount Washington, where researchers can keep close tabs on them and human activity keeps predators away, before being moved to more remote wilderness.

It seems that the wild marmots mentor the captive bred marmots, helping them pick up key skills such as how to interact with the colony or how to plug their hibernation burrow successfully.

In the Vancouver Island Marmot’s case, captive breeding and re-introduction have provided the tiny wild population with the numbers and genetic stock it needed to grow. Since that low point in 2003, the Marmot Recovery Foundation, together with their funding partners, private donors and partnering zoos, have slowly, steadily, improved the marmot’s lot.

McAdie estimates that about 10 percent of the current wild population was born in captivity. While that percentage is small, those captive-born marmots have been key in recolonizing many sites from which marmots had disappeared.

Much of the marmot’s habitat had also been choked out by trees, which have been expanding as temperatures have climbed, McAdie explains. This is bad news for the marmots because they need open space to see approaching predators. So the group has been physically removing trees to preserve the meadows that these creatures need.

The foundation is also working to re-establish colonies further north on Vancouver Island at sites that are predicted to be less impacted by climate change.

Looking to the Future

The efforts have paid off. Today the wild population is up to 150 to 200 marmots and is producing up to 50 marmot pups a year. That bodes well for sustained population growth, but there’s still a way to go before the foundation’s goal of reaching annual pup production of 150 in the wild.

“The big lesson from the Vancouver Island marmot is that we can work with species that are on the absolute brink of extinction, and we can bring these species back,” Taylor says. But “it’s not an easy road.”

The news came as a surprise, albeit a welcome one, to Joel Sartore, National Geographic fellow, photographer, and founder of the National Geographic Photo Ark, who photographed this marmot at the Toronto Zoo.

“I never thought I'd see this species alive,” says Sartore, who since 2005 has travelled the world photographing species before they disappear.

So far, he’s photographed about 8,500 species. “I see more clearly than ever that all species are beautiful and have a basic right to exist,” Sartore says. “Besides, just think of how diminished our planet will be if we lose half of all species to extinction by the turn of the next century, as has been predicted.”

Work like that of the Marmot Recovery Foundation can help save individual species, but it often requires intense and continuing effort.

"We have re-established the population, but we really need to keep working in order to achieve a stable population that’s able to persist on its own,” Taylor says.

To that end, the group continues to breed and release marmots into the wild—with thirteen released this year so far. They also remove trees to preserve meadows and track down marmots that have strayed into unsuitable habitat and relocate them.

The group is ironically working toward a day when their efforts are no longer necessary—which they would welcome, as it would mean the animal would be recovered. “Our last job is going to be to thank our partners and our donors and turn off the lights,” Taylor says.

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park