Native American imagery is all around us, while the people are often forgotten

For indigenous people, everything from the word “America” to the insulting ways native symbols are used is a reminder of how those of European ancestry nearly killed a culture—and still misrepresent it.

The problem began with one word: “America.”

That word, honoring Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, was coined in Europe in 1507, when it was used on a map of the New World. But back then, the only Americans were indigenous. It was our world, but it wasn’t our word.

By the time the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, white people were simply referred to as “the Americans.” My ancestors were called American Indians. It’s a label twisted by accidents of history: The Italian explorer who gets his name on two continents and another Italian, Christopher Columbus, who dubbed indigenous people “Indians,” presumably because he thought he was in the East Indies.

American Indian: Two labels we didn’t choose. We might have been called something else. Columbus wrote on October 11, 1492, of encountering handsome people who “are of the color of the Canarians [Canary Islanders], neither black nor white; and some of them paint themselves with white, and some of them with red, and some of them with whatever they find.”

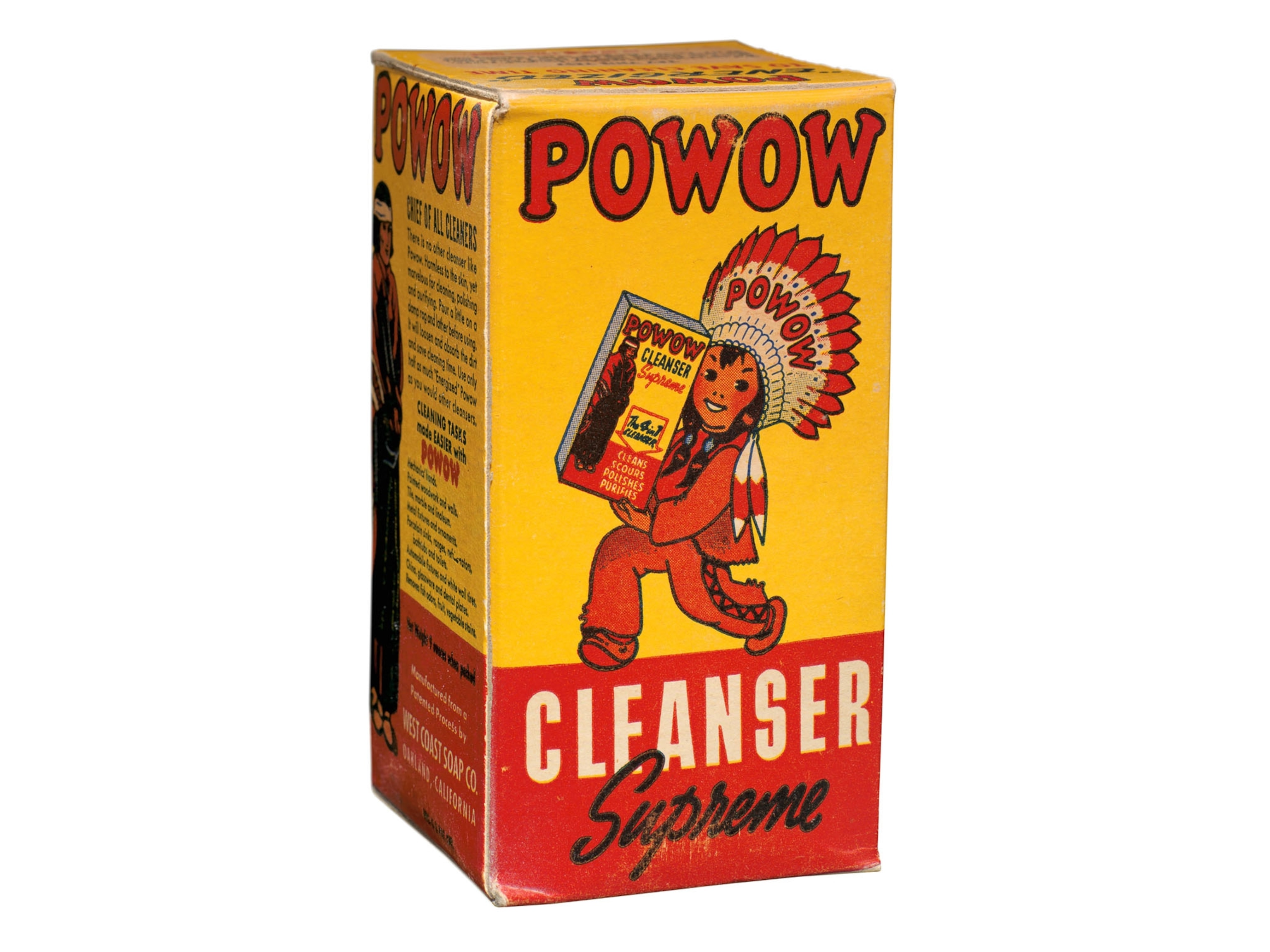

Canarians. Imagine if that name had stuck. These days American Indian symbols are everywhere. Think about all those college and high school football teams and their mascots. Think of Washington, D.C.’s National Football League team and the Major League Baseball teams in Cleveland and Atlanta. Think of boxes of butter. Or motorcycles. Or beer.

Indians are less than one percent of the population. Yet images and names of Indians are everywhere.Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, “Americans” exhibit, on display in Washington, D.C., until 2022.

They are caricatures, symbols of the European-American narrative that ignores the genocide, disease, and cultural devastation brought to our communities.

Our ancestors built indigenous cities such as ancient Cahokia (east of St. Louis, Missouri) and Double Ditch (north of Bismarck, North Dakota). But the First Nations often are dismissed as “rural,” or not urbane. Benjamin Franklin, for one, saw the richness of the native culture—and government—that was already here. He wrote in 1751, praising the Iroquois confederation of Indian nations, that “has subsisted ages and appears indissoluble; and yet that a like union should be impracticable for ten or a dozen English colonies, to whom it is more necessary, and must be more advantageous, and who cannot be supposed to want an equal understanding of their interests.”

Signs of indigenous culture are ubiquitous in America. But the people they represent are often forgotten.

The image of the American Indian as a marketing tool is partly rooted in the trade networks between indigenous people and European Americans. Native people excelled at trade. My favorite story about that comes from my own tribe’s encounter with the Lewis and Clark expedition in the early 1800s. The journal for the Corps of Discovery, as the expedition was called, mentions trading weapons to the Shoshone for horses. Days later, the journal complains that nearly every horse had a sore back. The pistols, ammunition, and knives were the better score.

But the story sold to the new Americans was the fiction that endured, enhanced by dime-store novels, shows such as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and eventually, Westerns on TV and film.

Wars and diseases such as smallpox destroyed the world that was. With that destruction came invisibility. A recent study said that “contemporary Native Americans are, for the most part, invisible in the United States.” The report, called “Reclaiming Native Truth,” cited “the impact of entertainment media and pop culture” and “the biased and revisionist history taught in school.” It also noted “the effect of limited—or zero—experience with Native peoples.”

The ideals and people of the United States are better than this history. Yet it often still seems OK to mock the first Americans. A president can slur a woman with “Pocahontas,” and it’s not career ending. When my son played high school football, I would cringe when his team played a team called the Indians, knowing that ordinary, good people would chant silly, made-up songs and wear cartoonish paint and feathers. It’s beyond imagination that such disrespect would be shown to any other group.

Americans need to evolve. We need to think about why Civil War monuments are falling, yet Kit Carson, Andrew Jackson, and other Indian-killers remain celebrated.

It’s time to make Native Americans more visible. Explore the richness of our history and culture. Quit supporting insulting imagery and labels. It’s time to be real Americans.

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park