A current of sound runs through my bones. Mallet in hand, I stand inside the scaffolding of a massive steel sculpture, on a grassy hilltop, in the middle of nowhere, which feels, right now, like the center of the universe. Artist Mark di Suvero equipped his installation “Beethoven’s Quartet” with mallets almost as a challenge: how wild do I dare to be?

There are no plaques describing this solitary sculpture. Why Beethoven? There is no explanatory information but the art itself, the wind, and the deep drum-like roar that will be heard only if I strike the metal again and make it. It’s up to me to create this moment, or to let it drift away.

Is it really OK to be this loud? Is it even OK to be here? Yes. It’s very OK.

The sentiment comes to me with clarity, just as many others will this weekend, out here in this Montana expanse that is the weirdest, wildest, windiest, and most wonderful combination of nature and art, of shared music and private moments, of impossible structures trucked in, hauled up, built on-site, and in some cases literally created from the earth below my feet—all seemingly dropped from the sky.

Wrapping up its third season, Tippet Rise Art Center, set on a 10,260-acre cattle and sheep ranch with the Beartooth Mountains fringing the horizon, is one of the newest of the world’s burgeoning outdoor cultural centers. But it’s already drawing some of the leading lights of modern art and classical music to the mostly unknown, unincorporated little community of Fishtail, Montana.

I’m here to spend the weekend immersed in art and music, and to see if doing so in the outdoors, isolated from my daily rhythms, makes a difference. Will it sprinkle some sort of magic dust over me—or will I just get dusty?

At first it looks like a monster bison grazing in the yellow rolling hills. But it is neither bison nor mythical Minotaur. It’s a massive, humped, and spiky sculpture called “Two Discs” made by Alexander Calder in 1965. It spent six years in front of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in my hometown of Washington, D.C. Now it’s here, out of context, freed, set out to pasture, and shape-shifting—not always benevolently—as I move toward and then past it.

I learn that Tippet Rise is unlike any art gallery I’ve ever been to. You don’t take steps between the artworks; you traverse miles of gravel roads and connecting trails, your view of each piece changing with your distance from it. What looks like a lonely sentinel from afar becomes, up close, a playful giant offering shade. Nothing is what it appears to be, and at first it all seems too big to absorb.

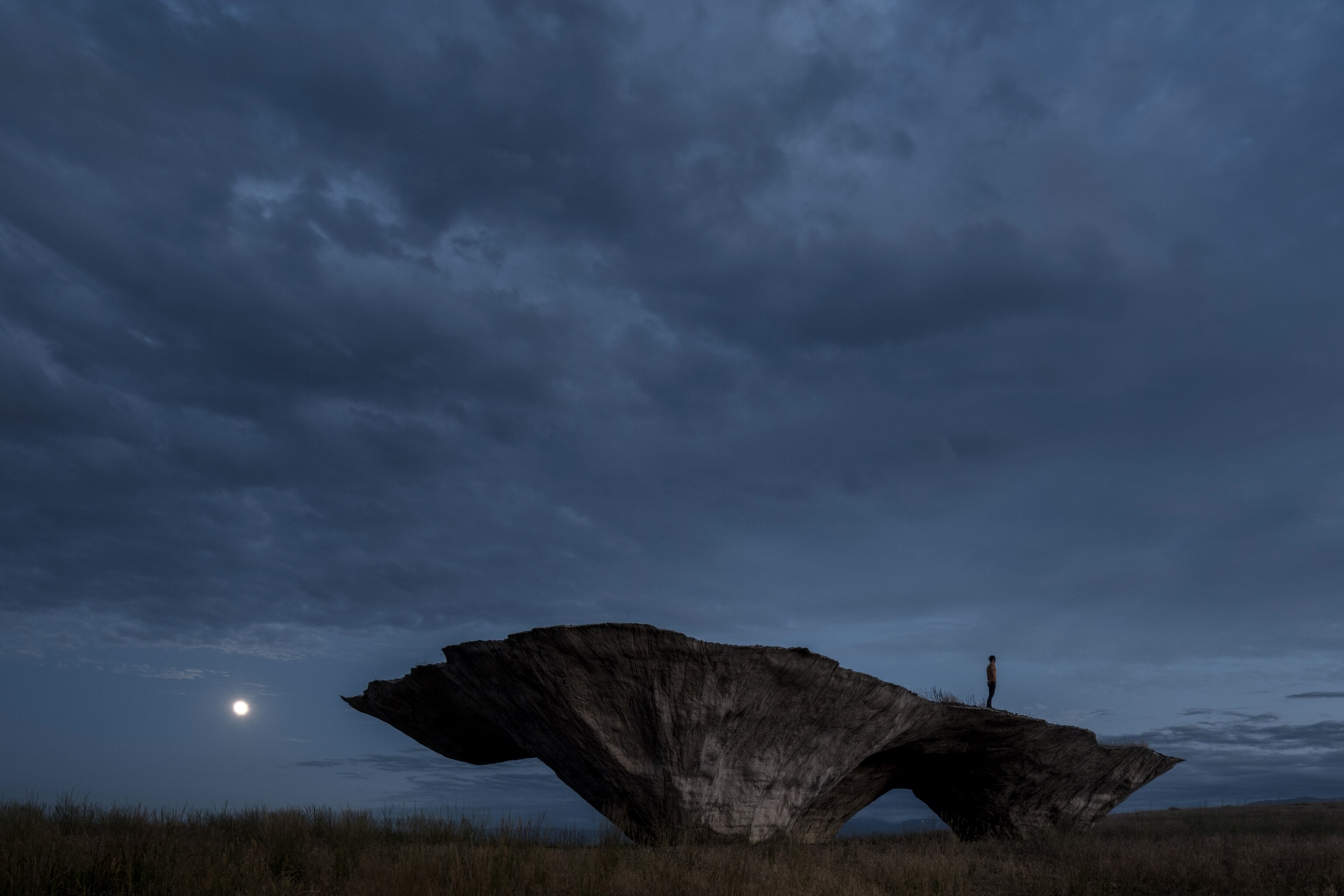

There is “Beartooth Portal,” a monumental sort of clamshell that in the hazy air serves as a curious druid beacon, made by an artistic architectural group called Ensamble Studio. There is “Satellite #5: Pioneer,” a giant wood and steel installation by Stephen Talasnik that seems equal parts knotted wooden rollercoaster and space satellite, fallen to this stretch of Montana that the artist has spoken about in unearthly terms: “The topography of Tippet Rise is reminiscent of the lunar surface, as seen in the early black-and-white images captured by NASA satellites, an expansive infinite panorama that served as a staging area for exploration and adventure.”

Now coiled out here, among the tall grass and snakes, this fallen satellite raises more questions than answers and looks as out of place as I feel. But I find that I like feeling out of place.

There is, however, logic in the design, as I learn later from Tippet founders Peter and Cathy Halstead. For one, the remote installations—made by architects and artists you’d see in top museums around the world—each get their own canyon, hill, glade, or natural amphitheater as a frame. The eight pieces out on the working ranch’s grazing lands also serve as cairns, way stations both fanciful and practical to help you on your journey, whether it’s by foot, bike, van, or in your head.

And it turns out several of the pieces are purposefully meant to feel as if taken from the sky. Their map on the land is a mirror image of the stars, Cathy tells me, “as if you took the constellation Orion and brought it down to Earth.”

Dwarfed, standing in the breeze that runs like a river through “Inverted Portal,” I run my hand along the smooth side of this 26-foot-high installation that was literally cast into, filled in, then removed from the earth and set upright with tractors and cranes. It’s cool to the touch, perhaps one reason why the Tippet Rise cattle tend to favor it for shade. Just one of the slabs can be measured in hundreds of thousands of pounds, one side of which, as my guide (and Tippet director of operations) Pete Hinmon calculates, weighs about the same as “400 grand pianos.”

Aside from the cows, there are other visiting luminaries from the animal kingdom: elk, deer, bunnies, eagles, sandhill cranes, and meadowlarks, to name a few. A group of students from Montana State University is also touring today, and when I see them later their faces are marked with dark charcoal-colored streaks; inspired, they had dipped their fingers in the rough sides of the primal sculptures.

At “Domo,” a massive rock structure also made by Ensamble Studio, the silence is punctuated only by a sort of ghostly castanet orchestra of grasshoppers. Hinmon tells me how a cellist who performed here once said that he “loved the accompaniment of the grasshoppers—if only they’d keep time!”

I notice two hikers, the next closest gallery viewers, walking toward us on a distant trail. I know they have piano concerts way up here, and I ask how they get Steinway grands up this hill of grass, brush, and gravel. The answer: very carefully, of course, with the help of a rough-terrain dolly set on inflatable tires and five or six people pushing the piano, on its side, up the hill.

This is when I understand that—for someone who works here—the weight of a grand piano is a perfectly legit unit of measurement.

It’s the middle of the day on “campus” and I stroll into the music barn where a small army of sound specialists is tinkering with the microphones above a glistening black, bison-size Steinway grand piano. I quickly learn that for people who live and breathe pianos, the 12 stored here—including one that belonged to the famed pianist Vladimir Horowitz—are referred to mostly as “she.” Some have names, and all come with entirely different personalities. One piano is “sharp” and “crisp,” another—like many built during the painful years of World War II—is “soulful.” The one that’s out now, called Seraphina and built in 1897, “is a good Chopin piano,” says Mike Toia, the self-described keeper of the keys.

Outside, dozens of guests start to arrive just as the afternoon air starts to cool. They chat over plates of BBQ and glasses of chardonnay in the breezy dining pavilion, called Will’s Shed, set with long communal tables. They too are pilgrims here, some of them from homes in the surrounding fields or mountains, others, like me, from farther away. I join the food line with the Montana State students—one of whom tells me with pride and surprise that she just realized she hadn’t checked the news once since arriving—and a slender man in an olive T-shirt I’ve seen throughout the day, a violin strapped to his back. He’s Kristopher Tong, part of the Borromeo String Quartet, which will perform two concerts tomorrow, one outside at “Domo.” He’s been rehearsing all day, but tells me that after his concerts he’s “hoping to explore and get lost.”

Eventually all the diners, perhaps a hundred of us, take our last sips of wine, toss our recyclable dishware, and stroll over to the music venue, called the Olivier Barn, for the evening concert, by pianist Jenny Chen. We sit in folding director’s chairs, and I note the informal dress code: fleece, checkered shirts, sweatshirts, hiking boots, cowboy boots, Tevas, and Birkenstocks. Cathy welcomes guests in a pullover shift and blue sneakers. Peter is wearing a faded pink fishing hat with a yellow band, jeans, and a fleece. I sense that they’re a big and welcoming presence here most—if not every—weekend, as they sit in their folding chairs, holding hands. Both seem as excited to be here as everyone else, the most permanent pilgrims of the lot of us.

Philanthropists, artists, and now grandparents, they want Tippet Rise—named for Cathy’s mother, who died young—to be an affordable oasis of art and music. (Van tours and concert tickets are $10, or free for anyone under 21; biking and hiking are free with reservation.) That’s because of how deeply they remember their own transformative life experiences in the early days of outdoor music and art venues: That summer when they ran through the sprinklers under the sculptures at the Storm King Art Center, or in 1981, when they visited the Caramoor Center for Music and Arts in upstate New York—a moment that was so life-changing for them that it inspired Tippet Rise.

It was during an outdoor concert that acclaimed pianist Ivo Pogorelich invited the entire audience to join him on his sheltered stage when rain began to fall. The rain, the pianist circled by the audience—everyone was joined together in one moment.

Such experiences, when the forces of nature can bring out new dimensions in a piece of art, a performer, or even a visitor, are something the art world is increasingly trying to offer cultural pilgrims around the world. And it’s exactly what the Halsteads are aiming for here, from art best viewed by mountain bike to musicians within arm’s reach of their audience.

“The stage is a barrier,” explains Peter. “When you make a stage, you make a wall. We wanted there to be no walls between the audience and the musicians.”

When her fingers hit the keys, I fall into a slight state of shock. How can 10 fingers create that much music? If I were not sitting so close I’d say it’s impossible. The sound seems to roll into the barn like a rushing wave, cresting with a deep sound rising up and around us, drifting back down the wooden walls like mist. This level of skill is now stopping me in my tracks, choking my throat, making it hard for me to see for a few minutes.

The Olivier Barn, where I now sit listening to Jenny Chen, is enclosed and built for acoustical excellence in what is known as a “jewel box” design, modeled on the dimensions of the intimate European halls where the greats such as Haydn and Bach performed. Concerts are held here on Friday and Saturday evenings. Most Saturday morning performances are at the outdoor installations, with guests driven up the gravel roads in two yellow school buses.

She performs just a few feet from us, and flashes of lightning illuminate the now darkened hills in the large window behind her.

Before she started to play, Chen described how Frédéric Chopin’s 24 preludes each represent a story and moment and that as she played we might look back at moments in our own lives as well.

She performs just a few feet from us, and flashes of lightning illuminate the now darkened hills in the large window behind her. I hear thunder between key strokes. Afterward, as the audience files out, the wind is a deep force, unchecked in this open valley of small hills.

In my rental car, in the growing darkness, I join the line of vehicles with the other pilgrims from the concert, heading out the gate. On the seven-mile gravel road back to Fishtail, our procession looks like a moving string of Christmas lights. I think about how all of us decorating this dark road just shared the same experience and are sharing it still, the miles between us growing so prettily.

The wind has violently whipped away several window screens of my rental house. I’m staying in Fishtail, near its one general store, since on-site housing at Tippet is for visiting composers, artists, and musicians. I reattach the screens, wary of the one door where I had accidentally flushed out a disgruntled bat the night before.

But what nature gave with the previous night’s colossal windstorm, it took away this morning: no outdoor concert. Rain could have been managed, but the wind was too dangerous for guests. Yet there’s a silver lining to nature’s unpredictability. Now that the string quartet’s performance has moved to the music barn, a large screen can be lowered, letting us follow the original music they’ll be playing, written by Beethoven in his own hand, ink smudges and all.

Before the musicians play, they teach us how to read Beethoven’s handwriting. He invented his own forms of notation, many so subtle that they never made it into modern sheet music, explains first violinist Nicholas Kitchen. He compares diving into the old manuscripts for the tiniest notes to the explorers who descended into the deepest ocean trenches “thinking there won’t be life down there.” But oh, how much life there was! The sweetest notes, to me, are the wiggly diamonds Beethoven drew to alert musicians to “a slight place for warmth and sincerity” in the music. He apparently got quite angry with musicians who didn’t follow his lead. Whether or not those details matter to us, Kitchen says, “those details really matter to Beethoven.”

In the barn’s intimacy, we’re able to ask questions of the musicians. They talk of facial expressions when playing, with the young violist Luther Warren saying that emotions sometimes come even before the music. “It’s more like a current and energy, sometimes you feel something is coming and sometimes you don’t. We channel that for you.”

Kitchen also adds that for him, it’s like “singing the music,” and the discussion roams to how people these days don’t sing together as much as communities used to. I feel a strange tenderness towards them. They’re here because we’re here. I realize we’re all part of the experiment unfolding right now. I’m as much a part of this as they are.

The quartet positions itself to play. Like the rest of us in the barn, I’m close enough to see that their cue to start is some sort of eye motion. I can see the violist, Warren, most clearly—his dark eyes fixed on the lead violinist, waiting for some secret starting gun to go off. His right arm is bent, his left extended, like a speed skater hunching with tension, his viola ready to race.

It’s only a one-room, frontier-style schoolhouse, but it’s easy to get lost in “Daydreams.” It, and I, are being enveloped, inside and outside, by cyclones woven from willow branches by the artist Patrick Dougherty. In Peter and Cathy Halstead’s book on Tippet Rise published by Princeton Architectural Press, Dougherty writes of touring turn-of-the-century schoolhouses that “still sit plaintively in the Montana landscape. These derelict remnants of learning occupy the most beautiful places and leave the explorer wondering how any child could concentrate in the midst of such allure.”

Stepping outside this prairie twister of childhood imagination and looking out at the hills, I realize that, with no visible power lines, this land is as close to what it looked like before. Before what, I don’t know. Before life as I know it, perhaps. I just know it’s beyond this place and time. It’s dead quiet except, after a few minutes, the wheels of a passing mountain biker stir the gravel path.

In their book, Peter and Cathy write, “Out of doors, a work of art is like a house dog let loose in a field,” spinning, reflecting the elements, freed. And so, they hope, is the artgoer: “You prowl, cavort, saunter, stalk. You have a relationship not only with the work but also with the grass and the temperature and the breeze.”

I was meant to feel out of place, let loose, freed. The college kids too, cavorting and stalking with their earth-streaked faces. The place is so abstract, so gloriously isolated, and puts so much muscle and thought into beauty that it serves as a lesson to me that the crazy effort is worth it, a life with more beauty and logic-defying is a life more worth living.

What I don’t yet know is that after this weekend I will also be listening to classical music in ways I don’t recall ever doing before. Until I listened to it actively, I hadn’t been able to think that one part of a piece might feel like a feather tickling your neck, another like a dizzying spin with a dance partner in a crowded room, the hems of imaginary dresses looping in wild abandon. I wouldn’t have mused whether, back in the days with no roller coasters or scary movies, maybe the adrenaline rush we all seek came with the music. I never really liked the wild parts of classical music until I slowed down enough to listen to the quiet parts, thrilled when the music finally becomes a torrent.

Tippet Rise itself is so intimate and sought-after that the center had to create a lottery for the concerts.

It’s possible I could have found my Tippet Rise, or something with a similar effect, elsewhere, earlier in life, closer to home. It might not be a place where size is measured in bisons or weights in grand pianos—a place of elks and art and ranchers—but equally magical.

Tippet Rise itself is so intimate and sought-after that the center had to create a lottery for the concerts. “It’s a good problem to have,” a staffer had told me. “Especially for classical music.”

Before coming here I had wondered if I’d be able to sit through three concerts—two in a day, one before lunch! I like to be on the move. But at the final concert—Bach, Mendelssohn, and the debut of an original composition created for Tippet Rise—I was on the edge of my seat.

The composer, Aaron Jay Kernis, who has been walking the grounds today, describes his music as inspired by this landscape: “ascetic” and “beautiful but rough.” The music does reflect the place: Pulled from the earth, dropped from the sky, seemingly out of nowhere. With its high violin notes, it definitely possesses a “beautiful but rough” sound, like cold snow falling on dry grass, perhaps something the composer had seen when he came here in winter to work on his original composition.

After the intermission, the quartet launches into Mendelssohn. I’m sitting near the college kids, who, like me, are positioned as close as possible to the stage-less players.

I’m so close I can see the musicians’ eyes, their fingers, their signals to each other. I can even see their feet. While their hands are making their instruments sing and soar, their feet slide and tap in a soundless dance, possessed by the sound. The sparkling heels of the cellist move so slightly, as if in a restrained, secret tango keeping time with her cello. The violinist—Kristopher Tong, the one I know is hoping to explore and get lost in the land tomorrow—has just the smallest hint of white gravel dust on his concert shoes.

What more evidence could I need that there is dust and magic dust in this place out of time.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction