Can you remember how you felt the first time you rode a bike? What about your first kiss—or your first heartbreak? Memorable moments and the emotions they trigger can resonate in our minds for decades, accumulating and powerfully shaping who we are as individuals.

But for those who experience severe trauma, such memories can be haunting, and brutally painful memories can leave people with life-altering mental conditions.

So, what if traumatic memories didn't have to cause so much pain? As our understanding of the human brain evolves, various groups of neuroscientists are inching closer to techniques that manipulate memory to treat conditions such as PTSD or Alzheimer’s.

For now, the work is mainly happening in other animals, such as mice. But as these initial trials show continued success, scientists are looking toward the potential for tests in people, while grappling with the ethical implications of what it means to change a fundamental piece of someone’s identity.

Feasibly, we could alter human memory in the not too distant future—but does that mean we should?

What Is a Memory in the First Place?

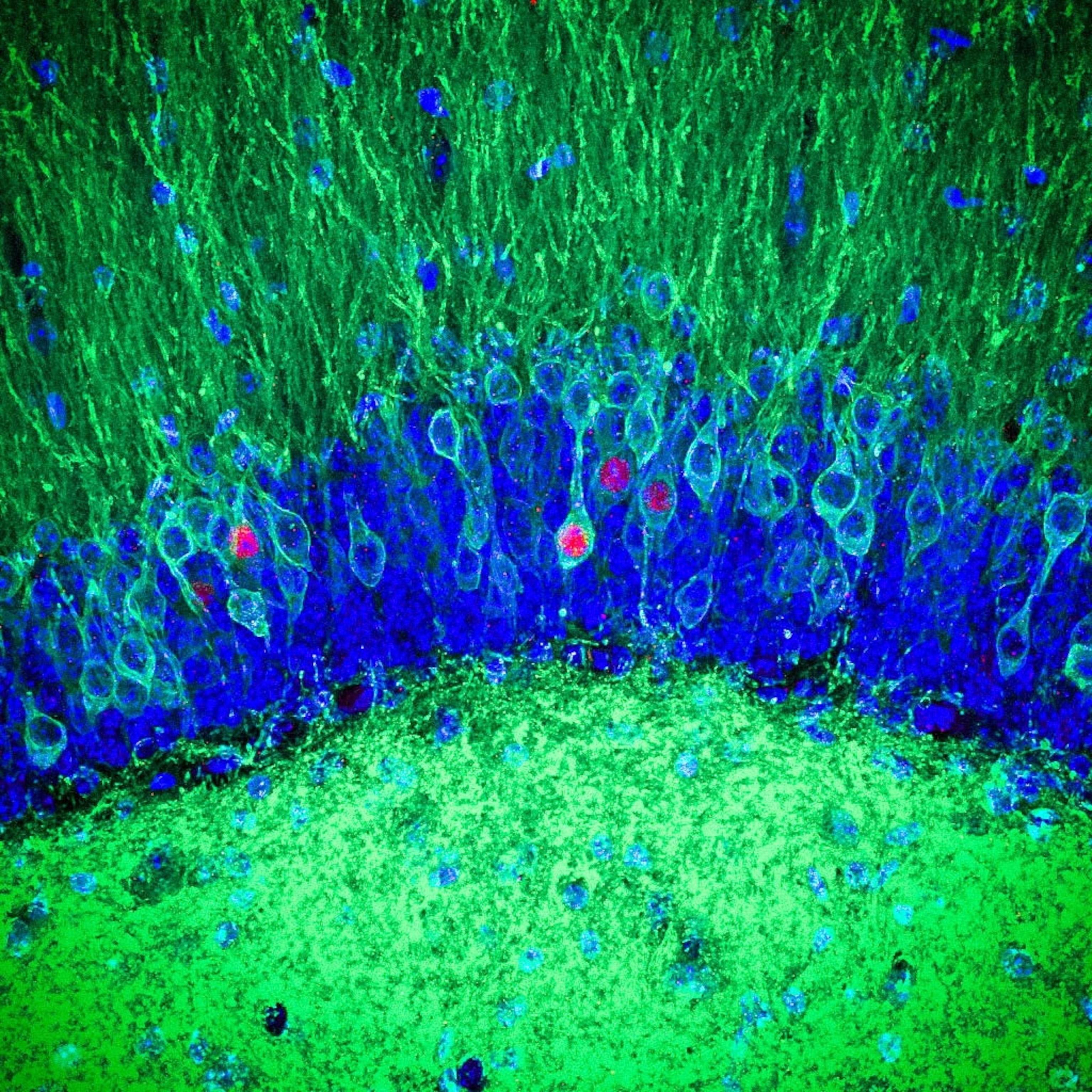

Neuroscientists usually define a singular memory as an engram—a physical change in brain tissue associated with a particular recollection. Recently, brain scans revealed that an engram isn't isolated to one region of the brain and instead manifests as a colorful splattering across the neural tissue.

“A memory looks more like a web in the brain than a single spot,” says neuroscientist and National Geographic Explorer Steve Ramirez of Boston University. That's because when a memory is created, it includes all the visual, auditory, and tactile inputs that make an experience memorable, and brain cells are encoded from all of those regions.

Now, scientists are even able to track how memories move across the brain, like detectives finding footprints in the snow.

While at MIT in 2013, Ramirez and his research partner Xu Liu had a breakthrough: They were able to target the cells that make up one engram in a mouse’s brain and then implant a false memory. In their work, mice reacted in fear to a particular stimulus even when they had not been conditioned in advance.

While mouse brains are less advanced than the human equivalent, Ramirez says they can still help neuroscientists understand how our memories work, too.

“The human brain is a Lamborghini, and we’re working with a tricycle, but the wheels still spin the same,” he says.

Copy, Paste, Delete

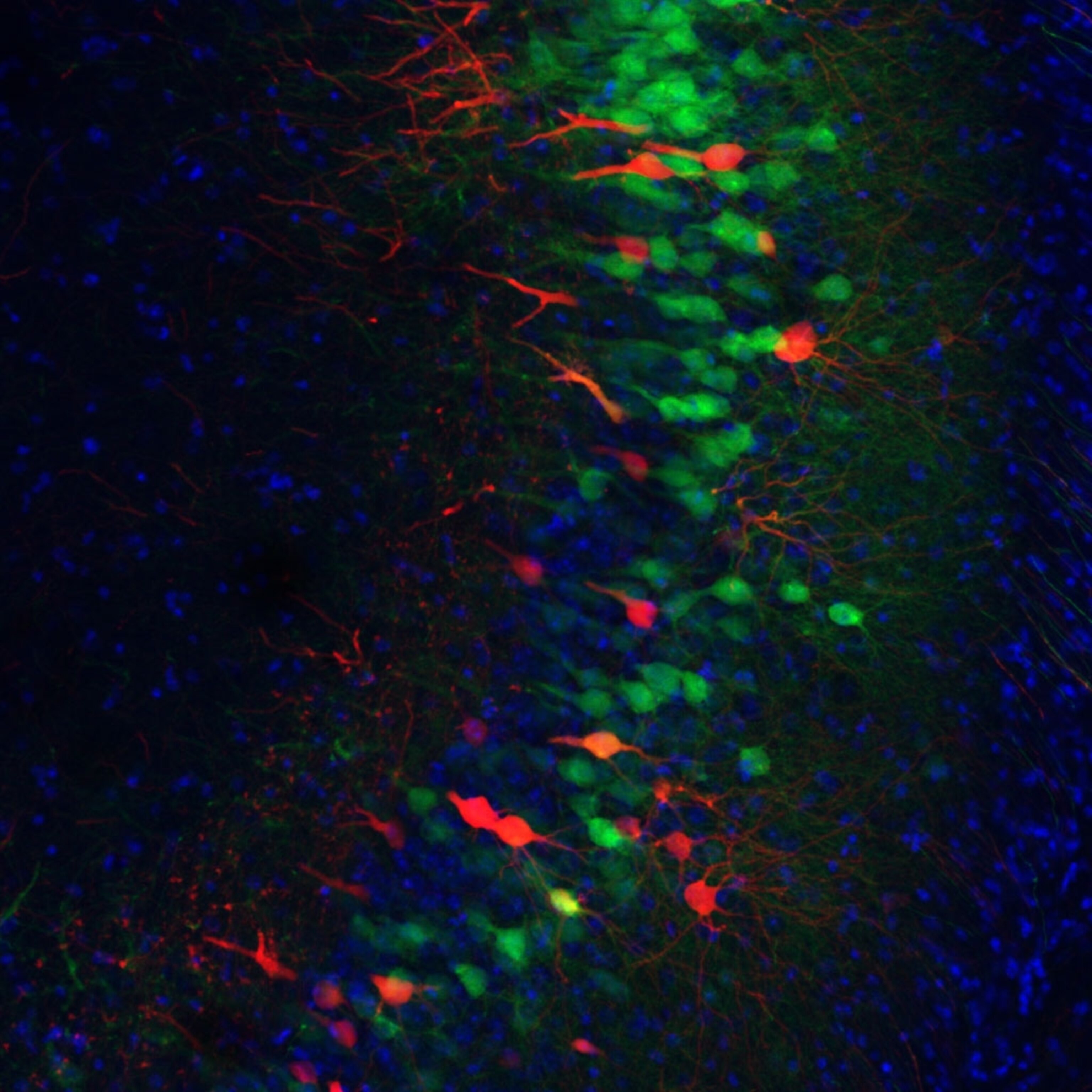

In their current work, Ramirez and his colleagues are investigating whether positive and negative memories are stored in different groups of brain cells, and whether negative memories can be “overwritten” by positive ones.

To prep mice for the experiments, the team injects the animals’ brains with a virus that contains fluorescent proteins and surgically implants optic fibers. The mice are then given a diet that prevents the virus from fluorescing until the researchers are ready to tag a positive or negative experience.

Positive memories are created by putting male mice in cages with female mice for an hour, and negative memories are created by putting the mice in cages that deliver brief foot shocks. Once the mice have been conditioned to associate certain triggers with each experience, they undergo a short surgical operation so the scientists can stimulate the cells associated with the positive or negative engrams.

They are finding that activating positive memories while a mouse is in a cage it associates with fear makes that mouse less fearful. The researchers think this memory “retraining” may be helping to eliminate some of the mouse's trauma.

“We use a positive memory to try to Etch-a-Sketch some of the memory,” says Ramirez. However, it's unclear whether those original fear memories are completely lost or just suppressed.

“If it was a Word document, we don't know if you saved it as a new document or [had] rewritten over the original,” says team member Stephanie Grella.

Using a different technique, University of Toronto neuroscientist Sheena Josselyn was able to completely eliminate fear memories in mice. After identifying the specific cells associated with an engram, her team made the proteins in those cells susceptible to diphtheria toxin, a disease mice can normally resist. Once injected with the toxin, those specific cells died, and the mouse stopped being afraid.

“It’s only a small portion of these cells, and the memory was essentially erased,” she says.

From Mice to Men

Both Ramirez and Josselyn stress that their work in mice is foundational, but they both see treatment potential for humans down the road.

“Traumatic memories could be rewritten with positive information,” says Ramirez. Those suffering from PTSD or depression could have their memories altered, for instance, so that they don’t have a strong emotional response to painful recollections.

Josselyn hopes the research currently being done on mice could also one day be used to treat people suffering from neurological disorders such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s.

But don’t expect to walk into a clinic and get your memories zapped any time soon, Ramirez says.

Trials on mice involve techniques such as shining blue light directly onto the brain, which means cutting into a mouse's skull and exposing bare neural tissue, a technique not likely to be used in humans. Future treatments could use infrared, a wavelength that penetrates human skin, Ramirez says, while Josselyn sees injected or ingested chemicals as the most likely option. They both say these tools are likely decades away.

But Should We?

If it's one day possible to alter human memory, who should be allowed to receive that treatment? Should it go only to those who can afford it? What about children? And would the justice system be at a disadvantage if key witnesses and victims can't remember a crime?

Those are questions New York University bioethicist Arthur Caplan says are worth thinking about now, even before the technology is ready for human clinical settings. He was among the early voices to weigh in on the ethics of CRISPR, a gene-editing tool that can now edit human embryos and potentially alter generations of people.

“I'm a big believer that the time to think through some of the ethics questions is long before the science is ready for prime time,” he says.

When it comes to manipulating memory, Caplan says scientists and lawmakers need to think about the minimal qualifications that would allow someone to receive this sort of treatment. It shouldn't be for everyone, he says, but possibly just for those suffering from severe PTSD and for whom other treatments have failed.

For instance, if the military can use this technique on veterans who suffer from PTSD, should they be allowed to alter the memories of soldiers who will return to war?

“Should they know if they've done terrible things? Does that stop them from doing terrible things again? Or do you want to risk having people who do terrible things, and then they're wiped clean?” he wonders.

As neuroscientists progress with their research, they say these ethical dilemmas are being taken into account.

“The idea of manipulating memories can and should be used in a clinical context,” Ramirez says. He sees the ability as neither good nor bad. Like water, it just depends on how you use it.

“Something that elemental can either be used for nourishing your body, or it can be used for waterboarding. If water can be used for good and bad, anything can be used for good and bad,” he says.

“I’m not 100-percent against,” Caplan adds. “You have to proceed with extreme caution.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico