Bizarre comet from another star system just spotted

Discovered by an amateur astronomer, the inbound object is only the second of its kind yet detected.

In the sleepy predawn hours of August 30, a Ukrainian amateur astronomer named Gennady Borisov spotted a strange comet zooming through our solar system. Now, astronomers have provisionally verified that the object, named C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), is moving too fast for it to be captured by the sun’s gravity—a sign that it’s most likely an interstellar interloper.

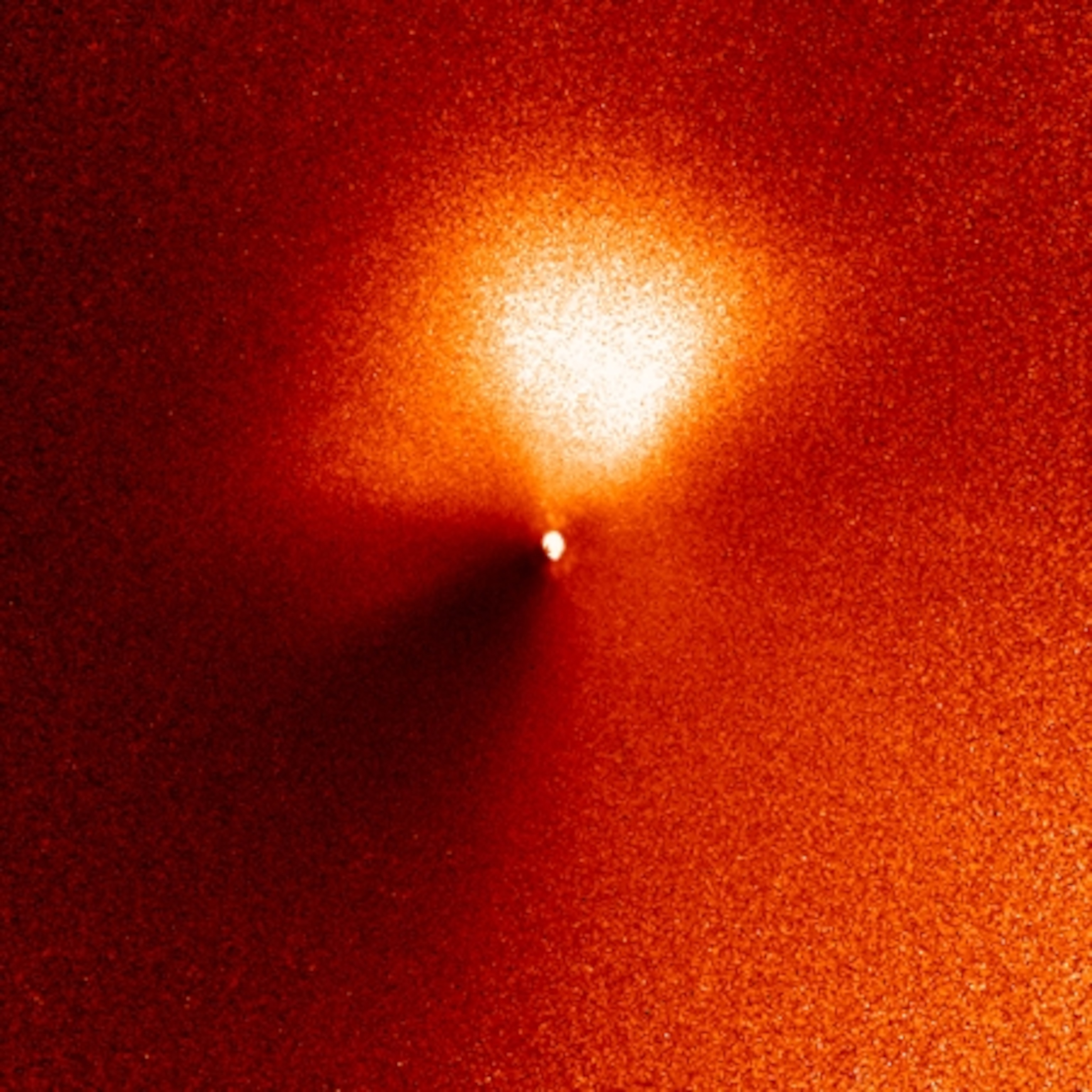

If these results continue to hold, C/2019 Q4 would be just the second visitor from another star system ever detected, after the 2017 discovery of the enigmatic space rock known as 'Oumuamua. While its origins are not yet entirely certain, C/2019 Q4 is a confirmed comet. Already, astronomers have detected that the object—which is probably a couple miles across—has a coma, the fuzzy sheath of dust and gas that forms as sunlight heats up a comet’s icy surface.

That means scientists will be able to collect much more data on its composition than they could for 'Oumuamua. For one, C/2019 Q4 is bigger and brighter, which offers more opportunities to study its light and tease out chemical clues. What’s more, astronomers discovered 'Oumuamua only on its way out of the solar system—but C/2019 Q4 is still inbound. It will make its closest approach to the sun on December 7, and it will come closest to Earth, within 180 million miles, on December 29.

“This is the first highly active object that we've seen coming in from something that formed around another star,” says Michele Bannister, an astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast. Bannister adds that observations of C/2019 Q4 can't pick up in earnest until mid-October, due to its position relative to the blinding sun. But then for months to come, astronomers will turn their gaze skyward to get what may be their best look yet at an interstellar visitor.

“What’s really fantastic is that this thing should be observable for a year,” says Matthew Holman, interim director of the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, which issued the verification of C/2019 Q4’s path through space Wednesday evening.

“We get to see one little bit of another solar system,” he adds, “and without necessarily knowing which one it came from, that’s exciting.”

Very eccentric

Borisov, a veteran comet hunter, found C/2019 Q4 by focusing his observations at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory on the low horizon to the northeast, in a patch of sky near the constellation Gemini. Astronomers tend to avoid peering into these “bright” patches of sky near the horizon, as they're difficult to see in and can damage telescopes’ sensitive optics.

Early reports of Borisov’s discovery made waves among astronomers. Quanzhi Ye at the University of Maryland first learned of the comet on Sunday, after a colleague commented on the object’s bizarre orbital track on a group email. Ye also noticed that Scout, a comet and asteroid-tracking service run by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, kept calculating that the object didn’t seem to have a circular or elliptical orbit.

In particular, Ye grew fascinated with one of the comet’s orbital parameters: its eccentricity. If an orbit’s eccentricity is zero, the object traces a perfect circle around its home star. The more elongated and narrow the orbit, the closer the eccentricity gets to one. If an object in our solar system has an eccentricity greater than one, it means the object has an arc-shaped trajectory and is making a one-time visit. The Minor Planet Center says that C/2019 Q4’s eccentricity exceeds three.

See stunning pictures of asteroids and comets

According to Ye, it’s unlikely that C/2019 Q4 was a comet that formed on the edge of the solar system and somehow got nudged into an escape trajectory. To get this kind of jolt, a comet would need to come close to an object large enough to alter its course, like a planet. But as far as astronomers know, C/2019 Q4 couldn’t have come anywhere near such usurpers within our solar system. The planets’ orbits around the sun more or less align in the same plane, but C/2019 Q4 appears to be dive-bombing the solar system at a 44-degree angle.

“That’s why we say that gravitational perturbations are almost impossible,” Ye says.

Telescope time

Astronomers estimate that at any given time, there's an interstellar comet or asteroid somewhere within the orbit of Mars, and 10,000 or so within the orbit of Neptune—but these objects are tiny and extremely faint, making them nearly impossible to see.

'Oumuamua, the first interstellar visitor detected in our solar system, rocketed through in the fall of 2017. Astronomers didn’t spot the strange object until it was on its way out of the solar system, hurtling along at 98,000 miles an hour. But in the little time they had, eager scientists around the world turned their telescopes toward the object, and they learned a surprising amount about this piece of cosmic debris. (Learn more about ’Oumuamua and what made it so strange.)

While the distant object only looked like a pinprick of light in the best of telescopes, its intense darkening and brightening every few hours suggested it was elongated, toppling end over end as it zipped through our solar system. Astronomers estimate that the object was anywhere between 590 feet to a quarter mile long but only up to 130 feet wide, giving the rocky body a pencil-like appearance.

Even more curious, 'Oumuamua didn’t keep racing along at the same rate. After flinging around the sun in early 2018, it unexpectedly sped up. Speculation immediately swirled as to the cause. Harvard professors Shmuel Bialy and Abraham Loeb presented one otherworldly idea: Perhaps it was a spacecraft using a solar sail sent by an alien civilization.

There’s almost certainly a more mundane explanation, though. According to other research, vents on the object’s surface could have released jets of gases that gave it a boost, in a spurt of cometary activity too faint for our telescopes to see. Or, 'Oumuamua could have been a glob of porous ices that was lightweight enough for sunlight alone to give it a nudge.

'Oumuamua left many mysteries in its wake that may never be solved, which is why the prospect of studying C/2019 Q4 in even greater detail has thrilled astronomers. When asked by email what he made of the Minor Planet Center’s verification, Ye responded: “Yeaaaaaaaaaaah time to grab telescopes!!!”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When does that become a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When does that become a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park