India's historic moon mission launches toward lunar south pole

The Chandrayaan-2 mission is aiming to be the first to land softly in the moon's south polar region.

Today, a shimmering golden spacecraft roared skyward on a pillar of flame at 5:13 a.m. ET. Known as Chandrayaan-2, the Indian spacecraft is now on its way to the moon’s south polar region, and if all goes well, its lander will touch down there in early September.

With this mission, India is aiming to become the first country ever to achieve a soft, controlled landing so close to the moon’s south pole, and just the fourth country ever to land softly on the lunar surface, joining Russia, the United States, and China.

Its scientific instruments will shed light on the moon’s mysterious interior and thin exosphere, and they will provide key details about the chemistry of the moon’s south polar region, one of the most compelling camping grounds for future lunar astronauts.

Want to learn more about this historic mission to the bottom of the moon? We’ve got you covered.

What is Chandrayaan-2, and why is it significant?

The Chandrayaan-2 mission is the latest lunar spacecraft sent to the moon by India’s national space agency, the Indian Space Research Organization, or ISRO. The mission aims to follow up on 2008’s Chandrayaan-1 orbiter, India’s first lunar spacecraft. Though the orbiter died prematurely—10 months into a two-year-mission—its data proved crucial in detecting frozen water on the moon’s surface. It also was an inspiration to India’s scientific community.

“Chandrayaan-1 in the last decade inspired so many levels within the country, and I am one of them; I started my Ph.D. in 2009 after the mission was launched, and I was an ISRO research fellow for the next seven years,” says Sriram Bhiravarasu, a postdoctoral fellow at the Lunar and Planetary Institute and a former member of the Chandrayaan-2 radar team. “It’s a big part of me.”

Chandrayaan-2’s safe descent would add to a remarkable string of successes for ISRO’s planetary science program. When the Mangalyaan Mars orbiter safely arrived at Mars in 2014, it made India the first country ever to successfully visit the red planet on its first attempt. ISRO’s science missions are also notable for their relatively low prices. Complex missions to other worlds regularly cost billions to build—but with a reported budget of $144 million, Chandrayaan-2 was less expensive to make than the science-fiction film Interstellar.

The new moon mission is setting another milestone, as the first in ISRO’s history where both key leadership positions are held by women. Muthayya Vanitha, the mission’s project director, previously worked on Mangalyaan, and Ritu Karidhal, Chandrayaan-2’s mission director, played a major role in ensuring that orbiter’s successful arrival at the red planet.

Where and how will Chandrayaan-2 be landing?

Three previous missions, including Chandrayaan-1, sent probes careening into the lunar south pole to throw up debris clouds on impact that overhead orbiters could chemically analyze. And in 2009, operators of the Japanese orbiter Kaguya (SELENE) guided the aging spacecraft into the ground near the southern Gill crater. But Chandrayaan-2 is designed to descend in a controlled manner and operate on the surface. Unlike Chandrayaan-1, which consisted only of an orbiter, Chandrayaan-2 includes an orbiter, a lander, and a rover. (See our newest map of the moon and every single spacecraft on it.)

To help ensure a soft landing, Chandrayaan-2 isn’t making a straight shot at the moon. It will start its trek by orbiting Earth, and its onboard thrusters will progressively take the spacecraft farther away over several orbits, until it sets course for the moon. Once near the moon, Chandrayaan-2 will fire its thrusters to enter a circular lunar orbit about 62 miles above its surface.

The orbiter will then separate from its precious cargo: the 3,243-pound Vikram lander. Vikram—named after physicist Vikram Sarabhai, ISRO’s first chairman—will then autonomously brake and scan the lunar surface to detect craters and possible obstacles.

If all goes well, Vikram will touch down on the moon on September 6, alighting onto one of two candidate landing sites between the crater Manzinus C and Simpelius N, at a latitude of about 70 degrees south. Strictly speaking, Vikram won’t be landing on the lunar south pole, but it’s by far the southernmost controlled landing ever attempted on the moon.

Soon after landing, Vikram will unfold a ramp, and Pragyaan will pop out. This 60-pound rover, named after the Sanskrit word for “wisdom,” is designed to cover a distance of 1,640 feet, powered by a 50-watt solar panel. Vikram and Pragyaan are designed to last an entire lunar day, or about two Earth weeks. Though it’s unclear whether they will survive the frigid lunar night, their orbiter companion will last for another year.

What instruments does the spacecraft carry, and what science will it do?

Chandrayaan-2 is carrying 13 scientific payloads: eight on its orbiter, three on the Vikram lander, and two on the Pragyaan rover.

The orbiter, essentially an upgraded version of Chandrayaan-1, carries a camera that can map the moon’s surface with 16-foot resolution. It also can map the surface occurrence of certain elements such as magnesium, and it will be able to detect the composition of the moon’s whisper-thin exosphere. One particular camera will provide Vikram and Pragyaan with high-resolution images of their landing site. And its radar system will be able to peer into areas of perpetual shadow within the poles’ craters. If “dirty ice” mixed with lunar soil is hiding there, Chandrayaan-2 will be able to see it.

Vikram’s payload includes a seismometer designed to detect moonquakes, and it will carry a probe to measure the density of electrons and other charged particles near the moon’s surface. The Pragyaan rover also packs a scientific punch: It will be lugging around a block of radioactive curium-244 that will spit out x-rays and high-energy particles. As this glow washes over nearby rocks, the elements within them will fluoresce, letting Pragyaan see their chemical makeup.

The mission’s overall goal is to better understand the distribution of water ice and other compounds preserved near the lunar poles, as well as the structure of the moon’s interior. Such research will help scientists better understand the origins of the moon and the solar system—and it will help future astronauts better map potential sources of water.

Though landing there is tricky, the lunar south polar region is arguably the best possible spot on the moon for humans. In addition to water ice and other essential materials, its elevated “peaks of eternal light” near the south pole’s Shackleton crater are nearly always bathed in sunlight, giving future explorers there a near-continuous supply of solar power. (Find out more about the surge of interest in visiting the moon’s south pole.)

But understanding where lunar water comes from and its current activity is no easy task. The moon likely has three distinct types of water: primordial leftovers from its birth, water ice brought to the moon by comet impacts, and water ions formed from scratch on the surface, perhaps from charged particles from the sun. So far, no one really knows how these various flavors of water interact.

“You can say there is a lunar water cycle, but we don’t know anything about it,” Bhiravarasu says. “This mission, if everything goes right with all the instruments we have on board, this would add a significant input to this puzzle.”

So where will India's space program go from here?

India’s space program shows no signs of slowing down, especially if Chandrayaan-2 succeeds. ISRO recently put out a call for international space agencies to contribute to Shukrayaan-1, a planned Venus orbiter that may launch sometime in 2023.

“Space is always brutal, you know—so with three successful missions, we should be going to more distant places,” Bhiravarasu says. “This should give a lot of confidence to ISRO as a whole to conduct more planetary missions in the next decade.”

In August 2018, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi announced Gaganyaan (“Sky Craft”), an ambitious ISRO mission to build and launch an orbital spacecraft for Indian astronauts by 2022. If Gaganyaan pans out, it would make India just the fourth country to launch its own astronauts into space on its own vehicles, joining Russia, the United States, and China.

The Times of India reported in 2018 that Gaganyaan faced a steep uphill climb, both in technical and budgetary terms. But on the crew side, at least, the space agency has reported some progress. In June, ISRO chairman Kailasavadivoo Sivan announced that the Indian Air Force would select 10 potential crew members by August 2019 and later select a final crew of three astronauts. And in July, ISRO signed an agreement with Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, to train these astronauts.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

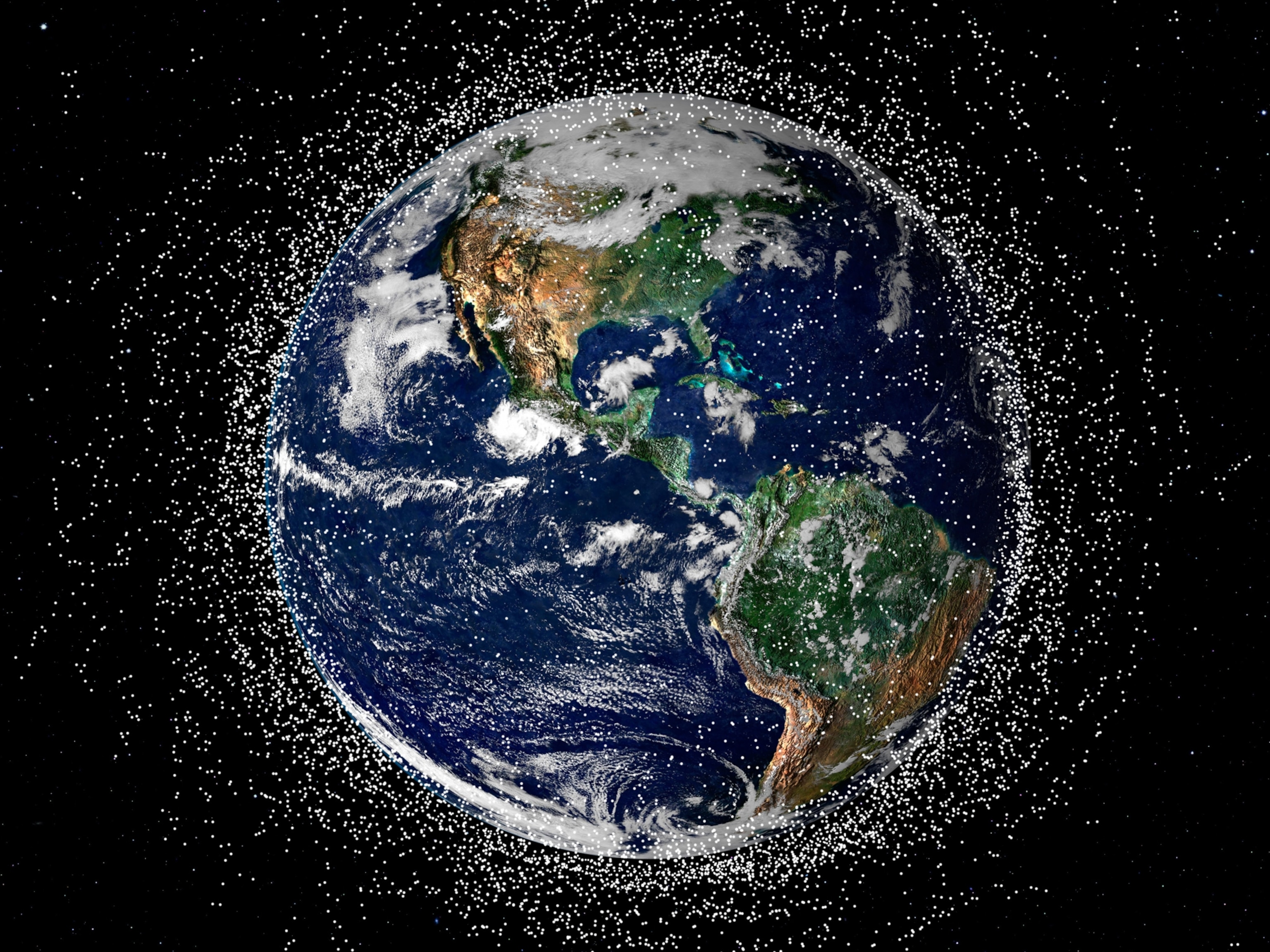

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park