More than 16 million years ago in what is now New Zealand, a giant bird died and sank to the bottom of a lake. Preserved in layers of sand and gray-blue clay, the bones of this behemoth have since been unearthed, revealing what is now the largest parrot known to science.

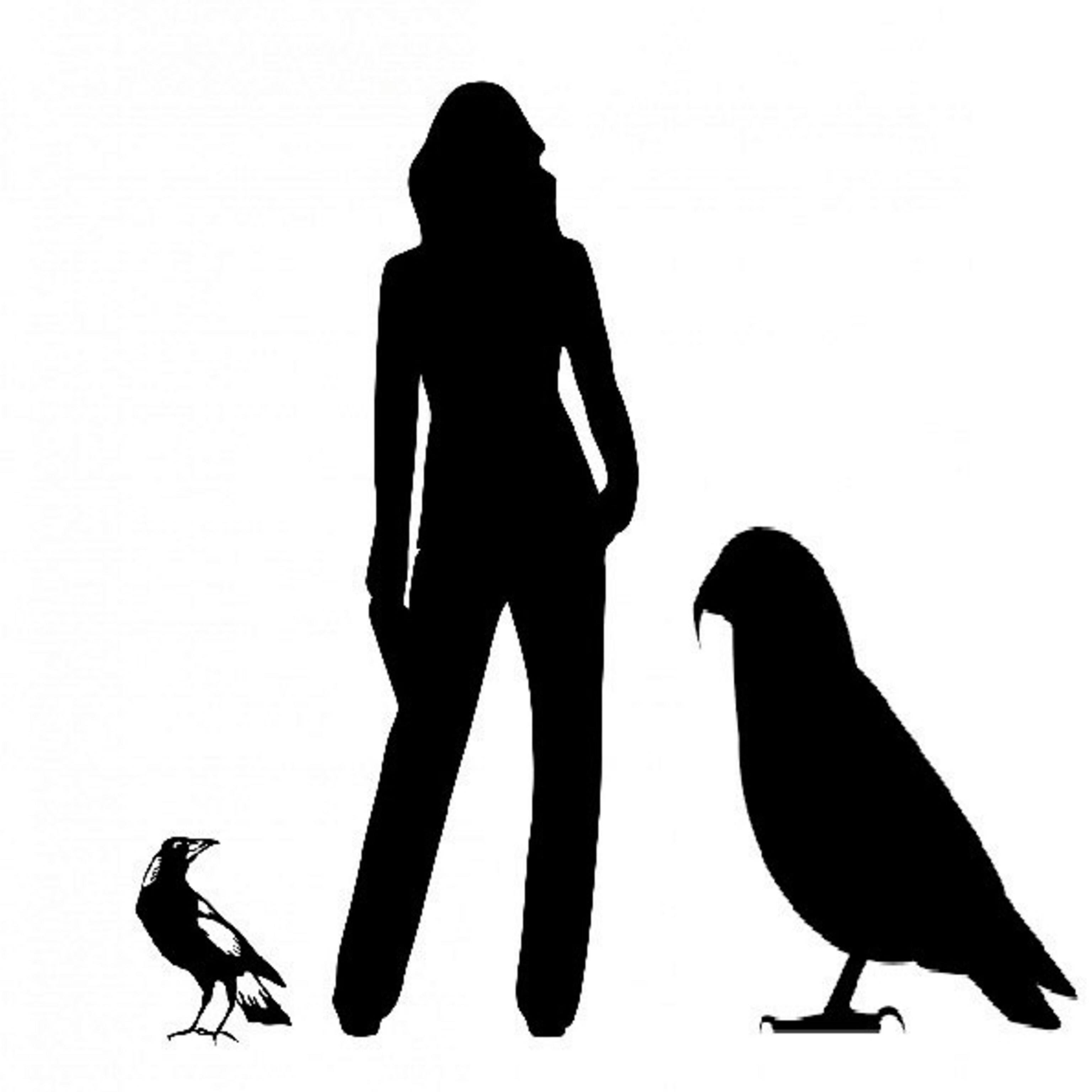

Of the 350 parrot species alive today, the heaviest is the kakapo, a flightless bird also native to New Zealand. But the extinct parrot, dubbed Heracles inexpectatus, crushes the kakapo’s record: Described from two fossilized leg bones, the bird would have weighed 15 pounds and stood roughly three feet tall.

That’s tall enough to be “able to pick the belly button lint out of your belly button,” says Michael Archer, a paleontologist at the University of New South Wales in Australia who is part of the team describing the find today in the journal Biology Letters.

“The [kakapo] is such an oddball, so it is amazing to think that it was perhaps part of a larger group of these flightless parrots that lived in New Zealand,” says Alison Boyer, an ecologist at the University of Tennessee who was not involved with the study.

Drumstick surprise

Researchers unearthed the big bird fossils in 2008 at St Bathans, a former mining town that sits on top of an extinct lake. The site preserved rich fossil deposits from the early Miocene epoch, including plants, crocodiles, bats, and dozens of bird species.

“Most of the specimens in the St Bathans fauna—more than 6,000 identifiable bird bones—are quite small,” says study leader Trevor Worthy, a paleontologist at Flinders University in Australia.

That’s why the large tibiotarsi, or drumsticks, of this bird stood out. For the next 10 years, the bones sat on a shelf with other presumed eagle bones from the St Bathans site, until a graduate student realized they were not actually from ancient eagles.

“It was completely unexpected and quite novel,” Worthy says. “Once I had convinced myself it was a parrot, then I obviously had to convince the world.”

Worthy and his team compared the leg bones to specimens and online images from various museums to whittle away at the list of potential species. Psittaciformes, the order that includes parrots and cockatoos, rose to the top.

“Based off what they were able to show here, it’s convincing,” Boyer says. “Parrots have a pretty distinctive morphology.”

The research team then estimated the size of the bird based on the circumference of the leg bone. Their equation doesn’t take into account the particular stance that a parrot has compared to birds in other families, says Helen James, curator of birds at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who was not on the team. But even if their estimate is not perfect, she agrees that this bird would have been exceptionally large for a parrot.

“It blows my mind,” says Andrew Digby, a conservation biologist with the New Zealand Department of Conservation who was not involved with the study. Digby works to protect the kakapo, which has teetered on the edge of extinction since the early 1900s.

“Every time someone sees a kakapo for the first time, the first thing they nearly always say is, Wow, it’s much bigger than I thought it was going to be,” Digby says. And kakapo “can be aggressive, if they want. My eyes open a little bit when I think about one twice the size. It could be quite formidable.”

“When you think about how smart parrots are, that’s scary,” adds study coauthor Suzanne Hand, a paleontologist at the University of New South Wales.

Squawkzilla on the prowl?

With only two leg bones in hand, many details about this bird’s behavior remain unknown. The heft and other small clues on the ends of the bones suggest that the giant parrot couldn’t climb or fly—Heracles most likely stayed on the forest floor.

It’s possible the large parrot survived on only the vegetation it could reach, Digby says. Moa, giant ground-dwelling birds that went extinct soon after humans arrived in New Zealand, were herbivorous. And pollen found in clay layers around the fossils show that the parrot lived in a balmy, subtropical climate. With more than 60 kinds of tropical fruit-bearing trees to choose from, Heracles would have had an abundance of options, Worthy says.

Still, getting enough calories from just leaves and fruits may have been challenging for such a big bird, and it may have needed to supplement its diet, Hand says. Meat-eating isn’t typical for parrots, but the birds have been known to be opportunistic.

This was Squawkzilla. This was a potential horror that was maybe eating other parrots.Michael Archer, University of New South Wales

Kea, a smaller parrot species native to New Zealand, learned to claw chunks of fat off the backs of sheep. They even drag seabird chicks—“little lumps of lard”—out of their burrows, Worthy says. The added nutrition gives these parrots a leg up during cold New Zealand winters. With no large carnivorous mammals sharing resources on the island, the mighty Heracles might have similarly jumped into this vacant niche.

“This was Squawkzilla. This was a potential horror that was maybe eating other parrots,” Archer speculates.

Big bird bonanza

If further digs eventually reveal the bird’s beak, looking at its shape could provide more clues. But Archer admits that few differences exist between the beaks of today’s omnivorous and herbivorous parrots, so paleontologists will need to keep eyes open for other evidence.

“Information about what it actually did [eat] might come from other parts of the deposit rather than the bird itself,” Archer says.

What paleontologists can say for sure is that the giant parrot fits into the larger story of New Zealand’s bird life. The island has long been disconnected from other landmasses, so no large mammals were able to reach it. Instead, birds had a strong foothold, and they were able to diversify into a wide array of sizes and specialties.

“We never imagined we would find a parrot of such gigantic size,” says study coauthor Paul Scofield, senior curator at the Canterbury Museum in New Zealand. But given New Zealand’s history of gigantism—including moa, rails, and eagles—the find isn’t completely unexpected.

“That is why this discovery of a giant parrot is exciting—it’s both predictable and surprising,” Christopher Witt, director of the Museum of Southwestern Biology of the University of New Mexico, writes in an e-mail.

“Paleontology is all about serendipity,” Worthy adds. “You just never know, and that’s what’s exciting about the game.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park