Like many parents around the world, burying beetles provide a cozy nursery for their offspring. Unlike most parents, however, Nicrophorus vespilloides beetles build that nursery by plucking fur and feathers from small animal carcasses and then coating the bare bodies with special secretions.

Now, a study published today in PNAS shows that the microbes in this beetle juice actually slow decomposition and instead help preserve carrion so that the developing larvae have a safe and delicious spot to mature.

“Carrion is nutritious but susceptible to microbial decomposition, which makes it a good system to study the dynamics between insects and their microbes,” says study leader Shantanu Shukla, an entomologist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany.

In the wild, the death of a bird, mouse, or other small animal is just the beginning for the next generation of burying beetles. Adults have receptors on the ends of their club-shaped antennae that recognize chemicals given off by decaying animals, including putrescene and cadaverine. (Meet the bugs that have gruesome jobs.)

“Burying beetles want the body fresh, but not too fresh,” says Jennifer Pechal, an entomologist at Michigan State University who studies interactions between insects and microbes.

Once they’ve found a body, burying beetles excavate a chamber in the ground into which they place their prize. Although a corpse may be 200 times its size, a burying beetle can transport the carcass to a chamber dug up to three feet away. After rolling the corpse into a ball, the beetle lays on its back, balances the body on top, and moves its legs to create a conveyer belt motion.

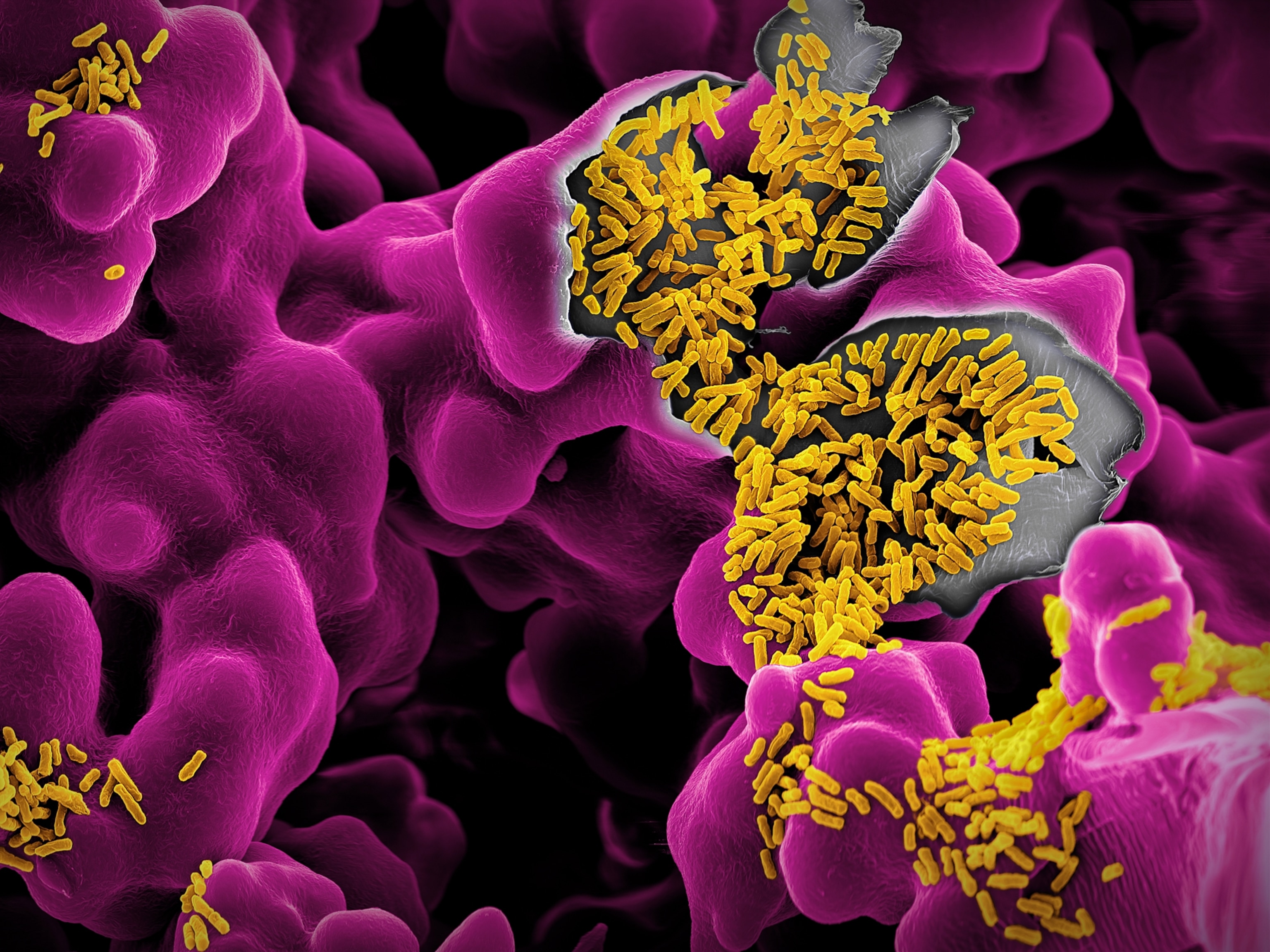

With the body in place, the beetles use their powerful jaws to remove any feathers and fur, and to chew out a section of the dead tissue to build a crèche for their squirming little larvae-to-be. They also coat the corpse with a layer of oral and anal secretions as a finishing touch. The female then lays her eggs, which hatch about 48 hours later.

Life from death

However, a dead body is also an attractive food source to a wide variety of species, including microbes involved in decomposition. The beetle larvae take several days to reach maturity, by which time bacteria, fungi, and other animals can consume an otherwise untended corpse. (See what happens after an adult elephant dies.)

That’s why the beetles coat the carrion in that bacterial- and fungal-rich fluid, Shukla and his colleagues found. This protective layer prevents the growth of other species that would consume the dead body. In addition, the beetle fluids contain antimicrobial compounds to further halt growth of unwanted species.

In the lab, Shukla compared the chemical profiles of beetle-tended and untended mouse carcasses. After nine days, the untended mice had essentially liquefied and become overgrown with a white fungus, creating an eye-watering stench. The mice with burying beetle larvae, however, didn’t even smell if you put your face close and took a deep breath. By the time the larvae have finished growing, they have generally consumed the carrion completely, leaving only traces of bone and body.

RELATED PHOTOS: HOW CATS, BATS, AND MORE BECAME HALLOWEEN ANIMALS

According to the team, the mice used as larval nurseries had lower levels of putrescine, cadaverine, and other biochemical markers of decay. Instead of being dominated by microbes involved in putrefaction, the beetle-tended mice were mostly covered with a type of fungus called Yarrowia as well as beneficial species of bacteria. (You are currently surrounded by bacteria that are waiting for you to die.)

The new paper “added some nice details,” but elements of the system still aren’t clear, says Daniel Rozen, an entomologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands who was not involved in the study. For instance, he asks, is decomposition halted just by the beneficial microbes in the beetle fluids, or do the carcass-munching actions of the larvae play a role?

“The upshot is that we’re still not sure how parents ‘ensure’ the right mix of microbial addition and subtraction, especially when both functions are added via the same parts of the beetle,” Rozen says in an email.

Whatever the full story winds up being, Pechal says, one thing is abundantly clear: “If it weren’t for burying beetles, we’d be up to our ankles in carcasses.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico