Dear Vega: The forgotten Soviet mission that flew around Venus

Thirty-four years ago this June, tiny balloons soared through our sister planet's skies—the only aircraft we've ever flown on another world.

Dear Vega 1 and 2,

I’m sorry that I forgot about you again. The other night, after not thinking about you for a long time, I woke up from a dream in which I imagined your stately balloons hovering through the yellow clouds of Venus, peering down at the sweltering surface below. You are the only robotic missions to ever fly aloft on another planet, and yet few people on Earth have probably heard of you. Even those who have, like me, often fail to recall your accomplishments. I sometimes think it’s funny what we remember and what we forget.

You each launched in December 1984, a few months after my birth, your double mission a joint venture between the Soviet Union and eight European countries, including what were then East and West Germany. You were twins, as most interplanetary spacecraft were in those days: a redundancy measure to ensure that at least one of you would complete your task. Your two-part name—Ve-Ga—is a contraction of the Russian words for your dual targets, Venera and Gallei, Venus and Halley’s comet.

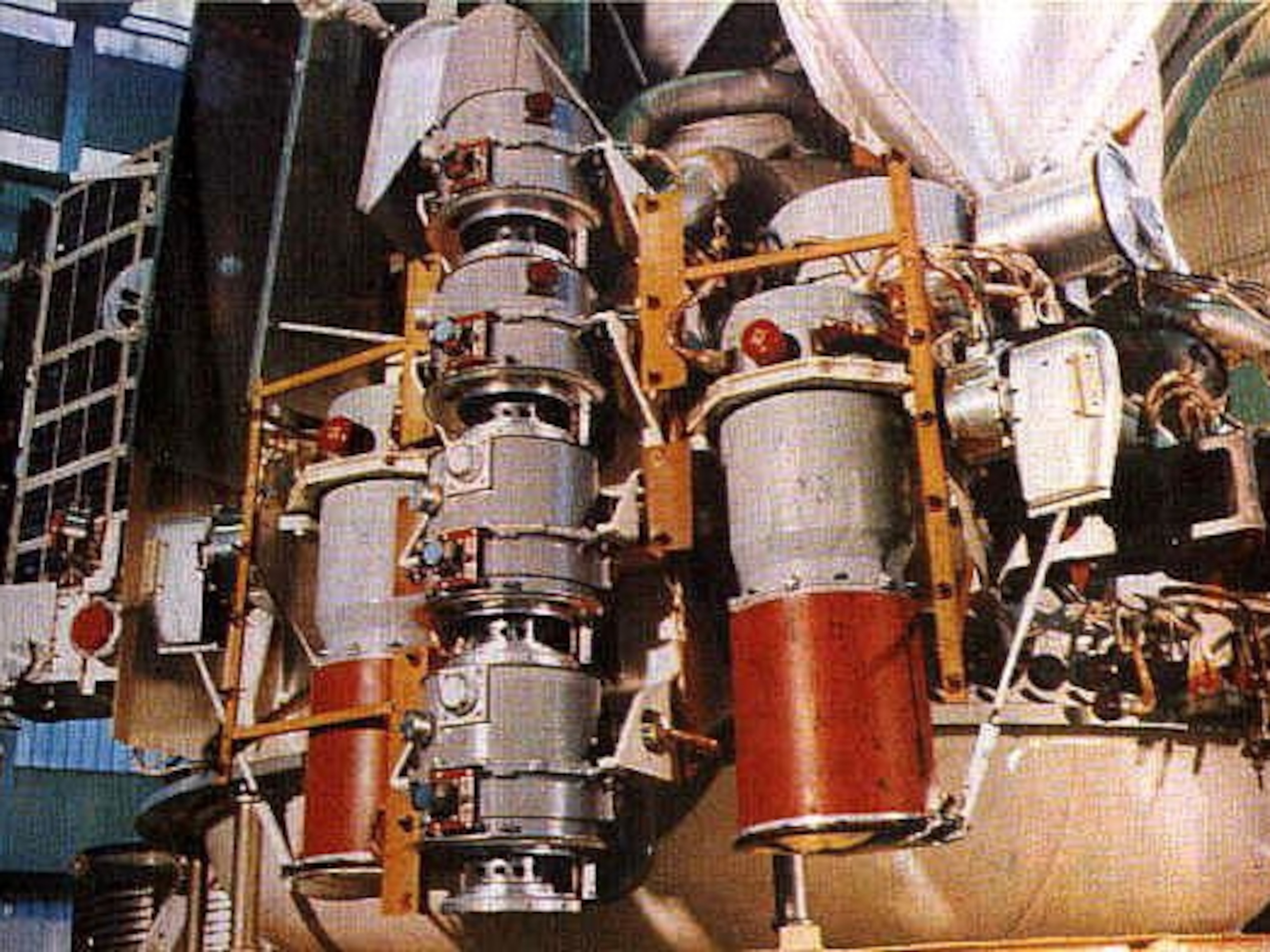

Thirty-four years ago, you had a rough arrival at our strange sister world Venus, enduring the equivalent of more than 200 times our planet’s gravity as you decelerated into the atmosphere. A series of parachutes slowed your fall and your onboard experiments recorded the presence of different gases in three distinct cloud layers. As your descent modules plummeted toward the surface, they split into two parts: a lander and a balloon package. The lander continued to drift downward, toward the hellish surface below, while your balloons inflated and floated away.

I want to know how the compressed helium in your canisters sounded as it rushed into your room-size balloons. A familiar kshhhh? Or perhaps something more otherworldly, a rumble that shook the thick Venusian air below? In either case, the timing had to be perfect. Should the balloons fill too quickly, they would burst in the low pressure of Venus’ highest altitudes. If the inflation went too slowly, the instruments would sink and melt in the fiery temperatures closer to the surface.

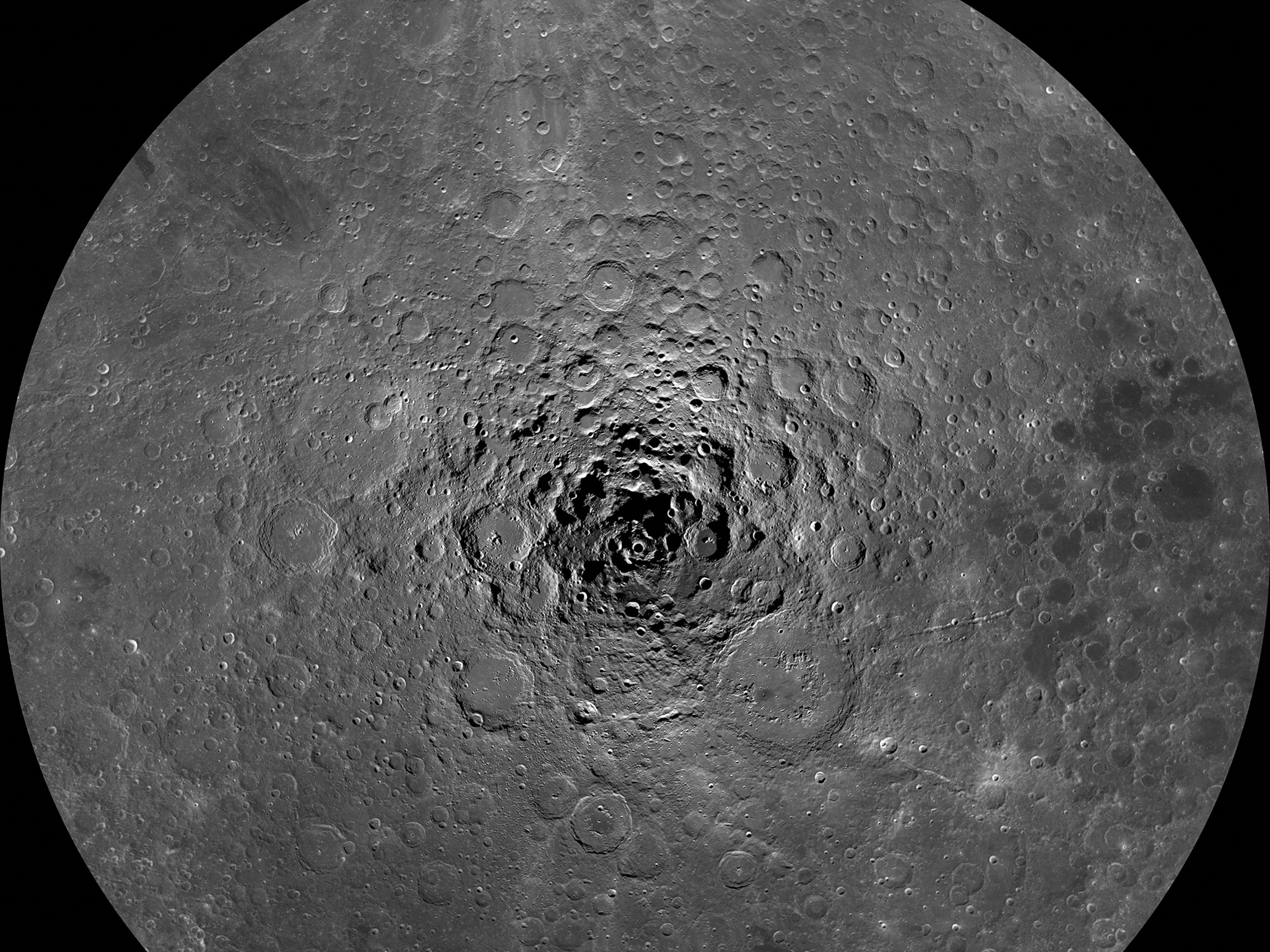

Thankfully, your balloons avoided these fates and flew during the Venusian night above a gigantic equatorial continent called Aphrodite Terra. The surface there is hardly a place for a goddess of love; it’s suffocating, downright infernal. But at your balloons’ airborne elevation 30 miles above the ground, the planet is a relatively clement place, with temperatures and pressures similar to those on the Earth’s surface. Were it not for the sulfuric acid clouds and hurricane-force winds, this slice of sky might be considered a veritable heaven.

Your balloons harnessed the 150-mile-an-hour breezes to drift a third of the way around Venus over the span of nearly two Earth days. As they traveled, their small gondolas took altimetry measurements that showed the balloons experiencing turbulence, sometimes bouncing up and down in mile-long lurches in the space of minutes. At one point, your balloon, Vega 2, might have even flown through a shower of sulfuric acid rain—recording the first precipitation on another world. Though they traveled at night, your instruments picked up bursts of light leaking through the clouds, most likely from the thermal glow of Venus’ super-hot surface. It’s even possible you saw lightning.

Fast Facts: Vega 1 and 2

Agency: Soviet Academy of Sciences

Vega 1 Launch Date: December 15, 1984

Vega 2 Launch Date: December 20, 1984

Launch Vehicle: Proton 8K82K

Vega 1 Venus Landing: June 11, 1985

Vega 2 Venus Landing: June 15, 1985

Launch Mass: 10,850 pounds (4,920 kg)

Your balloons reached the sun-facing side of Venus just after their batteries ran out of power. Nobody here knows how much longer they survived. Some scientists speculate that your inflatable spheres overheated and burst in the bright daylight—but I like to imagine that they stuck around long enough to watch the sun rise through amber clouds.

Meanwhile, your landers touched down on the oppressive Venusian surface. Each was modeled on the earlier Venera probes, which sent back our only photographs from the planet’s volcanic plains. Arriving at night, your contributions weren’t photographic; they were geological. Instead of cameras, your landers carried drills designed to operate only after their parts thermally expanded in the 930-degree-Fahrenheit environment. Sadly, your lander’s drill, Vega-1, broke from a mysterious electrical disturbance at the bottom of what’s called the shock layer in Venus’ lower atmosphere. But yours, Vega-2, was able to bore into the surface to deliver a sample revealing the soil’s igneous composition.

As if this wasn’t enough, you both then flew for nine more months to encounter Halley’s comet, which made its most recent appearance in our inner solar system in 1986. You joined an armada of other probes from Japan and Europe encountering the famous comet, cooperating with your robotic kin to improve your individual studies. With your television cameras, you sent back 1,500 images, revealing your target’s potato-shaped nucleus and observing shining jets erupting from it.

You also both flew twice through Halley’s tail, using aluminum shields to protect you from impinging ice crystals. You studied the comet’s chemical and gas composition and recorded turbulence in its odd magnetic field. Now, you float through the void on a sun-centered orbit, drifting until the day of your oblivion.

Despite these achievements—despite all that you endured—you are not well remembered among the champions of the space age, Vega 1 and 2. That honor tends to go to the first, or the biggest, or the most powerful of our robotic emissaries. Perhaps your studies were not the most outstanding, nor your assignments the most noteworthy. But you were the last probes to encounter the Venusian landscape, and you did so from a vantage point that no other craft has visited before or since: the Venusian sky.

Venus is not an easy place to love. The planet’s punishing conditions make survival on the surface fleeting. During the Cold War, the solar system was somehow divided by the two major spacefaring nations. The Americans had most of their successes with frozen Mars, while it fell to the Soviets to explore blistering Venus. Even now, our sister world is sadly neglected as a target for new missions.

It’s a shame that fame can only go to a handful. We toast the far-reaching Voyagers but not Pioneer 10 and 11, the groundbreaking spacecraft that preceded them. We celebrate the charismatic Apollo moon buggies but not the series of Ranger probes that helped make their adventures possible. Were it not for the fact that I’m a science journalist and that I was assigned to write about you a few years ago, I might have never even heard your name. I still go through lengthy periods where I forget that you existed—until you pop into my head. Then I smile and think, Oh yeah, we once flew balloons on Venus.

And so I wanted to tell you—and all the other unsung missions both big and small throughout history—I remember you.

Love,

Adam

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- Why this unlikely UK destination should be on your radarWhy this unlikely UK destination should be on your radar

- A slow journey around the islands of southern VietnamA slow journey around the islands of southern Vietnam

- Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?Is it possible to climb Mount Everest responsibly?