Hear more about camping on sea ice with whale hunters in our podcast, Overheard at National Geographic.

This story appears in the December 2018 issue of National Geographic magazine.

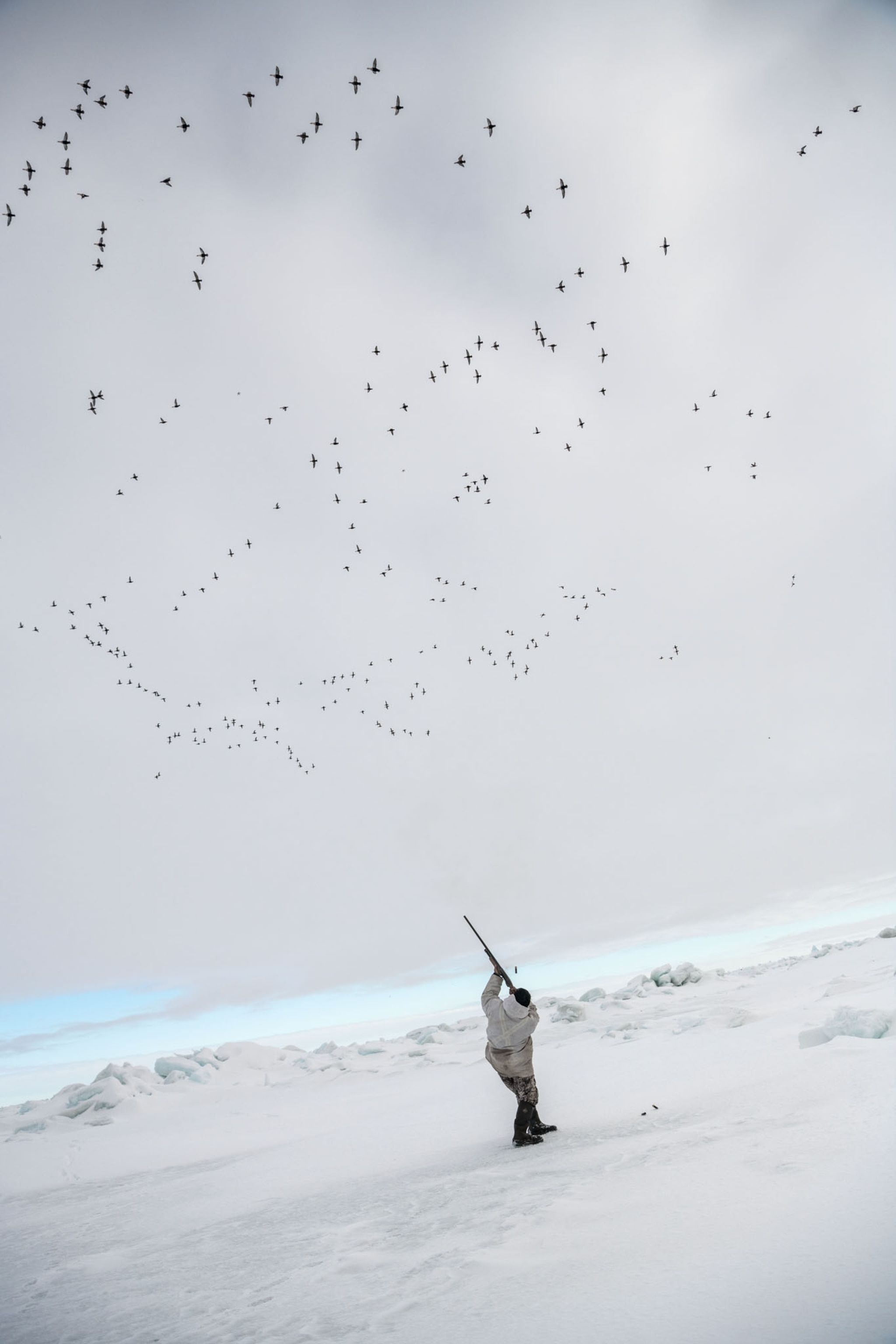

On the North Slope of Alaska, the culture of the Inupiat centers on whales. Each spring, men and women spend weeks on the tuvaq—the ice near the water—watching for bowhead whales migrating north from the Bering Sea to the Canadian Arctic. When one is spotted, a team pushes an umiak onto the water. There is typically one chance to harpoon the whale. If the hunt is successful, each person in the village can receive a share of the meat.

This story of cultural continuity enthralled photographer Kiliii Yüyan. Yüyan is indigenous himself, a descendant of the Hezhe (Nanai in Russian) hunters and fishermen of northern China and southeast Siberia. Stories portraying indigenous communities as degraded or destitute miss their complexity, says Yüyan. “You have to be with them to see their full hope and their joy.”

For 10 months in a span of five years, Yüyan lived among the Inupiat in Utqiaġvik (formerly known as Barrow). He camped with a crew on the sea ice to watch for whales, often volunteering for the night shift when the darkness and quiet set in. It’s a silence quickly broken, he learned: When a whale comes, a spotter calls out its position, urging the crew to launch. “When they’re close, [the noise] is not faint,” he says. “It’s notable. They sing songs. It’s like a musical.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital