The Mars rover Opportunity is dead. Here's what it gave humankind.

The spacecraft lasted more than 50 times longer than originally planned, delivering groundbreaking science and inspiring a generation.

After more than 14 years driving across the surface of Mars, the NASA rover Opportunity has fallen silent—marking the end of a defining mission to another world.

At a press conference at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, NASA bid farewell to the rover it placed on Mars on January 25, 2004: before Facebook, before the iPhone, and even before some of the scientists now in charge of it graduated high school. In its record-breaking time on Mars, the rover drove more than 28 miles, finding some of the first definitive signs of past liquid water on the red planet's surface.

“With this mission, more than other robotic missions, we have made that human bond, so saying goodbye is a lot harder. But at the same time, we have to remember this phenomenal accomplishment—this historic exploration we've done,” says John Callas, the project manager for the Mars Exploration Rovers mission. “I think it'll be a long time before any mission surpasses what we were able to do.”

NASA had not heard from the rover since June 2018, when one of the most severe dust storms ever observed on Mars blotted out much of the red planet's sky and overtook the solar-powered rover. Initially, the storm didn't give the team pause. From about November to January, the red planet saw seasonal winds strong enough to wipe accumulated dust from Opportunity's solar panels, which is one of the major reasons the rover lasted so long in the first place. But when “rover cleaning” season came and went without signals from Opportunity, hopes that it had survived began to dim.

On January 25, the team sent Opportunity a set of last-ditch commands, hoping that the rover had fallen silent because of malfunctioning antennae and an internal clock on the fritz. But the commands meant to fix this admittedly unlikely scenario didn't wake the rover.

Now, as Martian fall and winter overtake it, NASA says that the rover will remain forever paused halfway down a windswept gully, named Perseverance Valley for the rover's dogged effort.

The announcement marks the end of the record-smashing Mars Exploration Rovers mission, which built and operated Opportunity and its sibling rover, Spirit. The two rovers were each designed to go less than a mile and last 90 to a hundred Martian days, or sols. But the pair surpassed every conceivable expectation. After landing on January 4, 2004, Spirit drove hard through rugged terrain until it got stuck in 2009 and went silent in 2010. Meanwhile, Opportunity went farther for longer than any other vehicle on another world—and all other Mars rovers combined.

“It was one heck of a mission, wasn't it?” Mike Seibert, a former driver of Opportunity, says in an email. “I am looking forward to the future when Opportunity's records fall, because that will mean that we continue to explore our solar system. And I look forward to congratulating the team that puts Opportunity into second place.” (See amazing pictures from 20 years of nonstop rovers on Mars.)

“I always felt that were really two honorable ways for a mission like this to end,” adds Cornell planetary scientist Steve Squyres, the mission's longtime principal investigator. “One is simply that we wear the vehicles out. The other is Mars just finally reaches out and kills them. To have Opportunity go for 14-and-a-half years and then get taken out by one of the most ferocious Mars dust storms in decades—if that's the way it plays out, we can walk away with our heads held high.”

"Miracle" mission to Mars

Opportunity's path to Mars was as uneven as the red planet's rolling hills. The mission's core team spent more than a decade writing unsuccessful proposals to NASA, until the agency finally approved a two-rover mission by early 2000. But elation soon gave way to panic: The team had hoped for at least 48 months to build the two rovers, but they would get only 34.

And as the team raced against this deadline, engineers were also trying to reinvent how rovers are built in the first place. The rovers' most direct ancestor, the Pathfinder mission, consisted of a lander and separate rover. Here, JPL was trying to pack all the features of a lander into a rover, with far greater autonomy than Pathfinder ever had.

We worked hard, we designed it right, we did the due diligence and the engineering, and those things just lasted forever.Jennifer Trosper, NASA JPL

“People will say to me, It's a miracle it’s lasted so long, and I want to say, It’s a miracle we even got to Florida!” Squyres says, referencing the rover's launch site at Cape Canaveral. “The schedule that we faced to try to do something that had never been done before was just brutal.”

Teams led by project manager Peter Theisinger huddled to figure out how to pull off the build. JPL deputy project manager Jennifer Trosper, brought on to lead the systems engineering, recalls the effort as an all-hands-on-deck experience. Hardware and software were being tested in three eight-hour shifts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Even then, engineers were sending final software updates to the rovers while they were in space and en route to Mars.

“We had to bring it all together at once,” says Trosper.

The updates didn't stop once the rovers arrived on Mars. Eighteen sols after Spirit landed, Trosper's team suddenly lost contact with the rover. The days-long silence was made all the worse by the knowledge that whatever crippled Spirit may well claim Opportunity, which still was en route to Mars. But the team isolated the bug and fixed it, pushing an update to Opportunity on the fly. When Opportunity landed on January 25, 2004, it touched down without a hitch.

“We worked hard, we designed it right, we did the due diligence and the engineering, and those things just lasted forever,” Trosper says. “It's sad for me to see Opportunity go; it was always nice to have it there, still driving around as kind of a, Wow, that really worked well.”

Hitting the scientific jackpot

Originally, the team thought both rovers would last no more than 90 sols, based on expected dust accumulation on the rovers' solar panels. But the scientists hadn't accounted for winds on Mars to be strong enough to clean off the panels. Unexpectedly renewed with each changing season, the rovers did more work than anyone thought possible, and they now leave behind a towering scientific legacy.

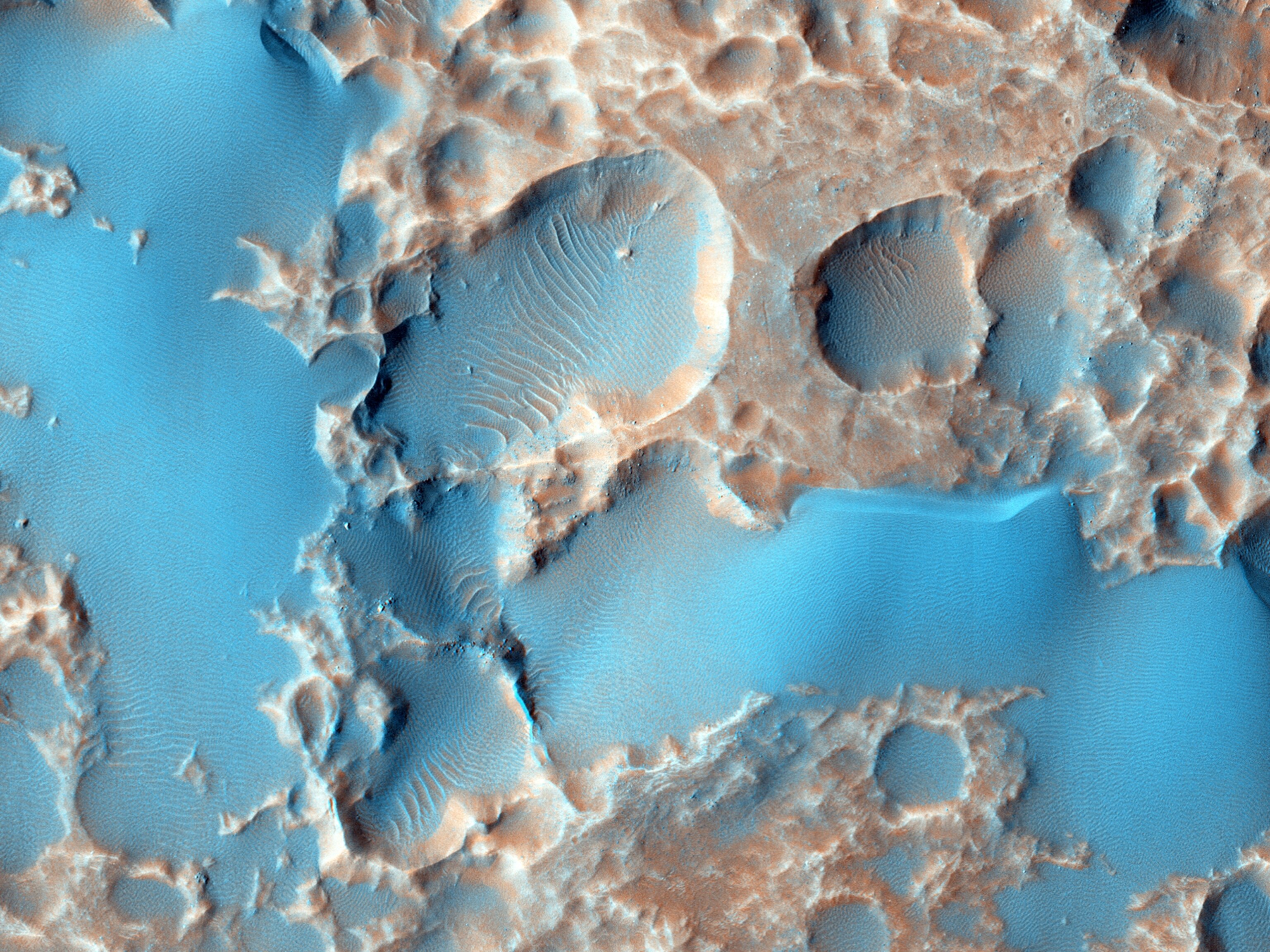

For decades, NASA's Mars mantra has been to “follow the water,” both with robots on the surface and satellites in orbit. But Spirit and Opportunity were the first to uncover definitive evidence that liquid water once existed on Mars for appreciable periods of time. Along the way, the rovers also revealed the red planet to be more complex and varied than scientists originally thought.

“When we first landed, I used to have this comforting notion that at some point, we would be able to sit back and cross our arms and say, Hey, we’ve done it, we’ve done our job,” Squyres says. “I underestimated Mars by a substantial margin.”

Opportunity hit the scientific jackpot from the very beginning. The rover's landing site provided scientists with compelling evidence that liquid water had been present beneath the surface and long ago flowed across the surface of Mars. That said, the water at Opportunity's first stop would have been more like a bottle of sulfuric acid than a placid lake or pond.

For the rover's first decade or so on Mars, studying the remains of this primordial acid bath was all in a day's work. Along the way, Opportunity ducked into craters, examined the impact site of its own heat shield, and discovered intact meteorites on the red planet's surface.

And when the rover arrived at the rim of Endeavor Crater in 2011, Opportunity was able to study rocks older than those at the first study site. These ancient formations—some of the oldest ever studied on Mars—held clay minerals and gypsum that showed that four billion years ago, neutral liquid water sloshed around on the surface of Mars.

“If you go back to our understanding of Mars 15 years ago, we didn't even know if there really had been liquid water on the surface in the past,” says Abigail Fraeman, the mission's deputy project scientist. “That's what Spirit and Opportunity showed us, that yes, there is incontrovertible evidence that Mars once had a very different climate. And answering that question has let us push beyond and ask even more complicated questions.”

Growing up Martian

Spirit and Opportunity's success not only paved the way for further robotic missions to Mars, but it also made the red planet more familiar to people back on Earth: a rich landscape of wind-carved hills and valleys that can be seen reflected in multiple landscapes around the world. (See how “astronauts” simulate a Mars mission in Oman.)

The twin rovers' anthropomorphic design also made it easy for people to place themselves alongside the spacecraft. And as the public got caught up in the journey—from beer commercials to LEGO sets—so too did future members of the rover's mission team. Fraeman was in high school when Opportunity landed and was able to be at the JPL that night as part of an outreach event.

“The fact that this has lasted from when I was in high school, deciding this is what I wanted to do for my career, all the way to where I got the training to do this as a career is pretty amazing,” she says.

Heather Justice, the rover's senior driver, also saw Opportunity as a touchstone. When she was in high school in Maryland, she saw a documentary about the rovers.

“For me, as a younger person, this was one of the really big NASA achievements: to be able to drive around the surface of someplace else,” she says. “I still can't believe how lucky I am.”

As Spirit stopped but the Opportunity mission went on, its human minders grew close. The children of mission scientists would hear of Opportunity almost as if the rover were a distant cousin. Pairs of rover drivers would spend so much time together, they'd practically read each other's minds.

“You start knowing everyone by first names,” Seibert says. “I’ve seen members of the team get their citizenship, people who gotten married, gone back to school, graduated. A lot of life happens.”

Now, the team has six months to wrap up and archive the mission's data and otherwise wind down what for some has been a fixture of their lives for decades.

“There's definitely some talk on the operations side of, wow, this might be the last time I get to work with some of these people,” says Tanya Harrison, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University and Opportunity science team member. “I think there'll be a lot of tears.”

Lasting legacy

While this may be the end for Opportunity, the study and exploration of Mars is far from over. The rover Curiosity is still chugging along, as are several Mars orbiters and the InSight lander. The European and Russian space agencies are readying their own Mars rover, recently named Rosalind Franklin after the pioneering x-ray crystallographer. And many alumni from Spirit and Opportunity are hard at work on the upcoming Mars 2020 rover, which will search for signs of past life and cache rock samples for future return to Earth.

In the meantime, Opportunity will stand as a monument to science for hundreds of thousands of years—and maybe even a site where future explorers pay tribute. Perhaps in coming decades, humans will touch down in Meridiani Planum, Opportunity's landing area. Some scientists and engineers, including Seibert, have formally suggested the region as a landing site for crewed Mars missions.

“That would be such a powerful moment,” Harrison says, “to have humans come face to face with the emissary that they sent there before them.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

- Why are these emperor penguin chicks jumping from a 50-foot cliff?Why are these emperor penguin chicks jumping from a 50-foot cliff?

Environment

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

- The U.S. just announced an asbestos ban. What took so long?The U.S. just announced an asbestos ban. What took so long?

History & Culture

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

- Why Passover is one of Judaism’s most important holidaysWhy Passover is one of Judaism’s most important holidays

- Is this mass grave a result of contagion—or cannibalism?Is this mass grave a result of contagion—or cannibalism?

- The surprising story of how chili crisp took over the worldThe surprising story of how chili crisp took over the world

- We swapped baths for showers—but which one is better for you?We swapped baths for showers—but which one is better for you?

Science

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

- 4 herbal traditions used every day, all over the world4 herbal traditions used every day, all over the world

- Ground-level ozone is getting worse - here's what that meansGround-level ozone is getting worse - here's what that means

- Would your dog eat you if you died? Get the facts.

- Science

- Gory Details

Would your dog eat you if you died? Get the facts.

Travel

- Why it's high time for slow travel in Gstaad

- Paid Content

Why it's high time for slow travel in Gstaad - The travel essentials we’re most excited for in 2024The travel essentials we’re most excited for in 2024

- How citizen science projects are safeguarding Costa Rican pumasHow citizen science projects are safeguarding Costa Rican pumas