The Wall of Frames

On Nat Geo’s wall of images, photographers ask: “So how do I get up here?”

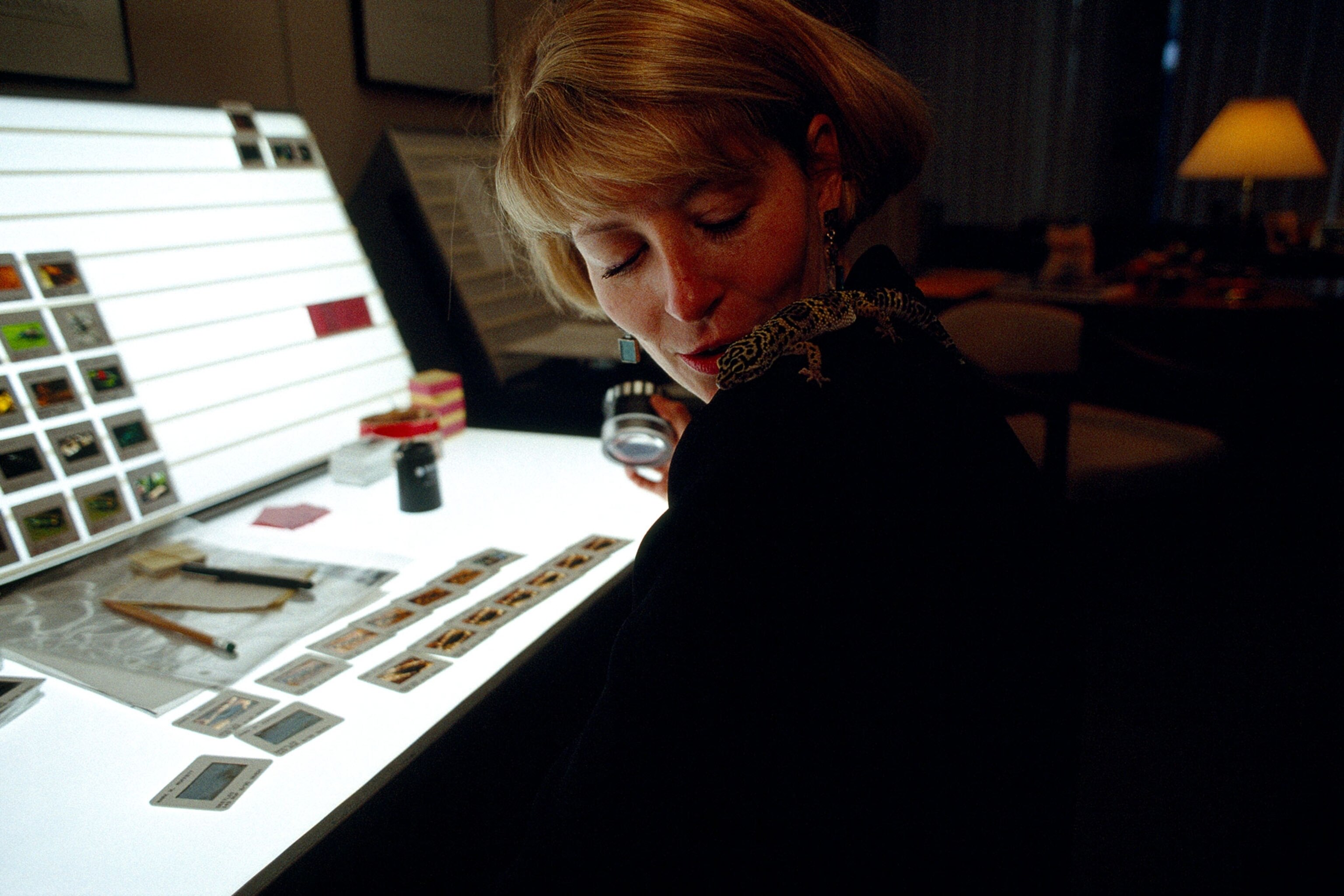

I find Kathy Moran at the unofficial entrance to National Geographic headquarters. Not the lobby on M Street, but an area next to the elevators on the fourth floor, which is home to Nat Geo's editorial staff. There’s a large wall there covered with a patchwork of oversized images taken by some of our most iconic photographers.

There are “frames,” to use the photographer’s parlance, by stalwarts such as Luis Marden, Thomas Abercrombie, Jodi Cobb, Nick Nichols, and Maggie Steber, as well as some by younger generations of photographers, including Lynsey Addario, David Guttenfelder, Erika Larsen, and Marcus Bleasdale, among many others.

It’s the closest thing we have to a “wall of fame” and is basically the first thing a new photographer sees when she or he arrives on the floor to meet the editors. And it’s the first thing veteran photographers look at when they come back to visit. I’ve had more than one photographer pull me aside and ask, “So how do I get up there?”

But I think of it as less of a wall of fame and more like the aleph in the short story by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. He imagined the aleph as a small sphere in which one could simultaneously see everything in the universe—past, present, and future.

This is trippy but stay with me.

The Nat Geo wall has 141 images that span more than a century, and each one represents weeks, months, sometimes years the photographer spent in the field to make it—not to mention the decades spent honing his or her craft. But each image on the wall is also a miniscule fraction of a second of recorded time. If you added them all up, the whole wall represents barely more than a second of elapsed time. Basically, the wall contains a century captured in the time it takes your to heart to beat once.

And yet the full spectrum of life is distilled there—plants, animals, and insects; oceans, deserts, and mountains; all in a riot of hues—ocher and aquamarine, violet and cinnabar. There are men, women, and children from a profusion of ethnicities, displaying joy, surprise, confusion, melancholy, suspicion, anger, despair. It’s all there on view, simultaneously.

There’s William Allards’ boy shepherd crying over his dead sheep in Peru. Paul Nicklen’s leopard seal bringing him a dead penguin in Antarctica. Amy Toensing’s Australian farmer and his children amid drought-stricken fields. David Alan Harvey’s Parisian women stealing a smoke. Randy Olsen’s African gold miner sweating under a load. And on and on, click, click, click.

Each image exerts its own gravitational pull like a planet. It’s common to see a staffer who, on the way to a meeting or the bathroom, has been unexpectedly pulled into the orbit of one of these worlds. What happened in the instant before the shutter snapped? What happened next? He or she stands there, silently staring, time traveling. (Here's what it takes to create enduring photographs.)

As National Geographic’s most senior photo editor with nearly 40 years on staff, Kathy knows this wall better than anyone. She points to an image that continues to transfix people all over the world—Steve McCurry’s image of Sharbat Ghula. With her piercing emerald eyes and enigmatic gaze, the world-famous Afghan girl sits at the very center of the wall. “I was the first person to see this one,” she says.

After McCurry made the picture in 1984, he shipped the rolls of film from Asia. Back then—long before digital photography—part of Kathy’s job was to inspect the freshly developed images. “I opened the envelope from Kodak, and there she was, something like 30 frames of her, with those unforgettable eyes.”

Kathy has stories about numerous photos on the wall. She’s edited most of the photographers up there and counts several as close friends. The wall has a gravitational pull on her, too, but it’s more personal, a chart of waypoints in her career, seasons in her life.

My plan for this essay was to get her to explain the process of finding these magical slivers of time. But that will have to wait. Kathy was recently promoted to oversee National Geographic’s still photography. And right now, she has to race to another meeting, and then there’s a call to a young photographer on the other side of the world, and then frames to edit, thousands and thousands of frames.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction