Who was Anne Frank? Why her legacy is still fought over today

Her famous diary offered a glimpse into life in hiding from Nazi persecution. Today, historians continue to investigate who betrayed her—and debate how to protect the Jewish teen's memory.

She described herself as a “little bundle of contradictions,” a willful, lively teenager who clashed with her mother, worried about her changing body, and dreamed of a better future. And in the decades after she died in a Nazi concentration camp, Anne Frank would also become one of the world’s most famous writers—known for the diary she kept for two years in hiding during World War II.

Anne was just one of six million Jews murdered by the Nazis between 1939 and 1945; just one of the estimated three-quarters of Dutch Jews who perished in concentration and death camps; and just one of the up to 1.5 million Jewish children who died in the Holocaust. But her words, and her life, have become potent symbols of the Shoah, of which she is arguably the most well-known victim.

Published in 1952, an estimated 30 million copies of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl have been sold to date. But who was Anne Frank, and why is her diary still discussed—and argued over—today?

Becoming Anne Frank

Born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, in 1929, Anneliese Marie Frank moved to the Netherlands with her family in 1934 in the aftermath of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. The Frank family was among the 25,000 Jews who had fled Germany for the Netherlands due to the Nazis’ growing persecution.

(Learn about Anne Frank's life with your kids.)

But the Franks—and all Jews—weren’t safe in the Netherlands, either. In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. Five days later, the Dutch government fled, and the country surrendered to the Nazis, who swiftly took over the nation’s civil institutions and began to impose the same restrictions on Jews that they had instituted in Germany. Among other laws, Jews were not allowed to use public transportation, practice various professions, or attend the same schools as non-Jews. Their bicycles, radios, and other items were confiscated and given to gentiles.

After the invasion, Anne’s father, Otto Frank, became increasingly concerned for his family. He managed to evade a law banning Jews from owning businesses by putting his company, Opekta, which sold pectin for home cooks, in the hands of sympathetic colleagues. But when an attempt to gain a visa to the United States failed, and Nazis began to arrest his Jewish friends and take them to concentration camps, he decided his family should go into hiding.

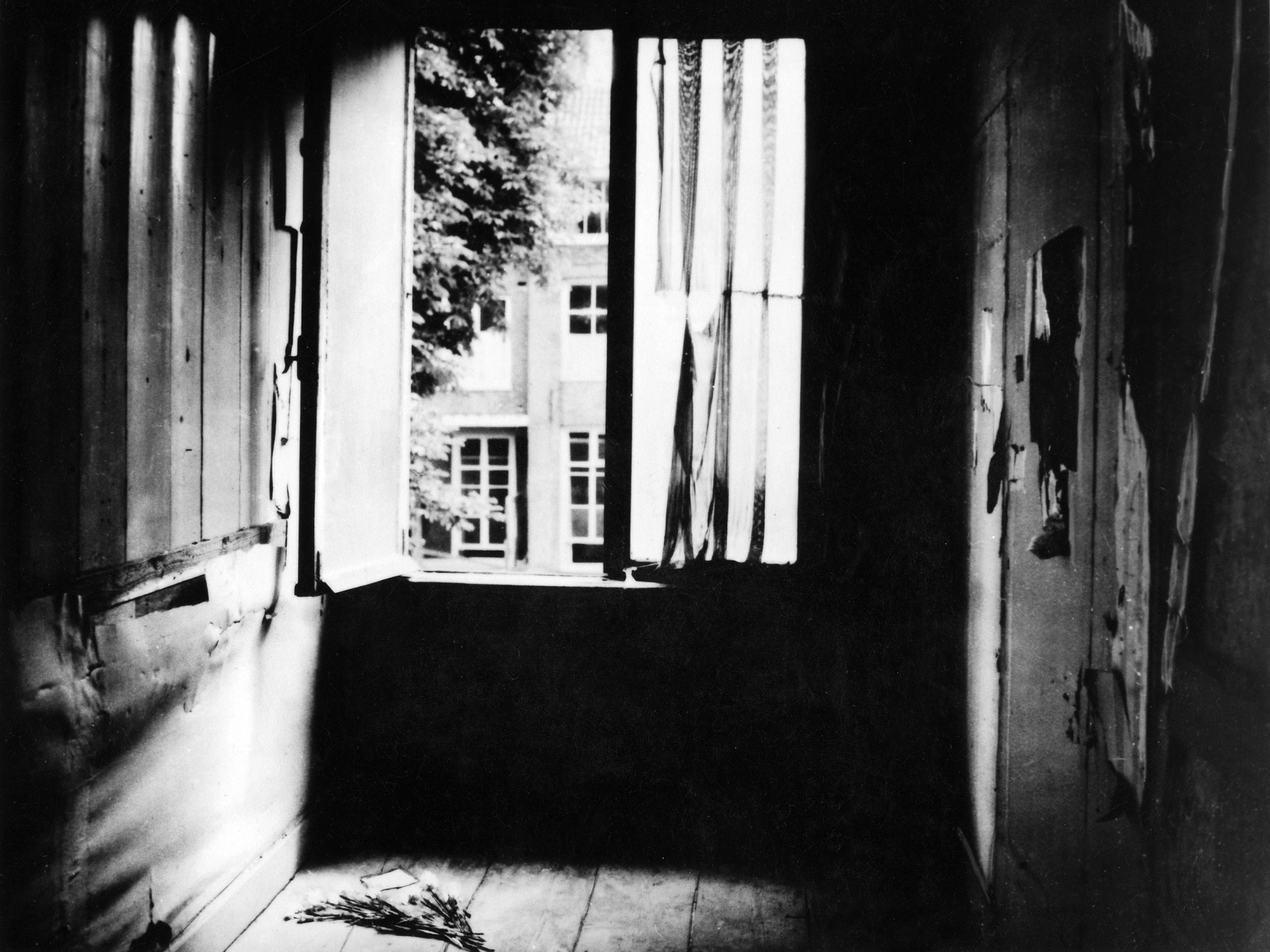

With the help of his gentile friends and colleagues, Otto arranged for his family to hide in living quarters behind Opekta’s offices. In July 1942, Anne, her parents, and her sister, Margot, moved into the cramped two-story apartment Anne would call “the secret annex.” They were joined by family friends Auguste and Hermann van Pels; their son, Peter; and Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist. The secret annex’s seven residents would not go outside for more than two years.

Hiding in the center of a bustling metropolis, the annex’s residents had to remain nearly noiseless during the day and withstand air raids at night. After dark, they huddled around a contraband radio and listened to news of the war. They were completely dependent on a small group of helpers, who bought them food on the black market and provided them with supplies and support at great personal risk.

Documenting life in the secret annex

Many of the details of life in the secret annex are only known due to Anne’s faithful documentation in her diary, which she received for her 12th birthday a month before going into hiding. Addressed to a fictional friend, Kitty, and written in Dutch, the diary was an outlet for everything from her complaints about her mother to her feelings about sexuality, human nature, and politics.

As the days dragged on and the pressure of war and life in hiding became nearly unbearable, the diary became Anne’s mainstay. She felt like “a songbird who has had his wings clipped and who is hurling himself in utter darkness against the bars of his cage,” she wrote in October 1943.

Anne had big aspirations for her account of daily life in World War II. In March 1944, she heard a radio broadcast in which a Dutch official in exile urged people to save historical materials related to the occupation and war. In response, she began editing her diary for publication.

“Ten years after the war, people would find it very amusing to read how we lived, what we ate and what we talked about as Jews in hiding,” she wrote. She called it Het Achterhuis, “the house behind,” and assigned the annex’s residents and helpers pseudonyms.

A life cut short

But her work was cut short on the morning of August 4, 1944, when Dutch police and German officers raided the secret annex and arrested Anne and the rest of the hiding Jews. In the aftermath of the raid, Miep Gies, who had been the Frank family’s main link to the outside world, gathered papers left strewn on the floor of the annex. Among them were Anne’s diary, which she put into safekeeping.

But Anne never came back. She was imprisoned first in Westerbork transit camp, then in Auschwitz, and finally in Bergen-Belsen, where she died of typhus in February or March 1945. Only one of the seven residents of the secret annex survived: Otto Frank, Anne’s father, who returned to Amsterdam in June 1945. When she learned that Anne was dead, Gies unlocked her desk drawer and gave Otto his daughter’s diary.

(The first official Jewish transport to Auschwitz brought 999 young women. This is their story.)

Anne’s father was fascinated and shocked by what he found there: evidence of a complex, deeply emotional young woman whom he had underestimated. He began to share portions of the diary with family and friends, then sold a heavily sanitized version to a Dutch publisher. In 1952, Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl was published in English.

It became a cultural phenomenon. After the success of a 1955 stage adaption by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich that won the Pulitzer Prize, the book landed on bestseller lists throughout the world.

Anne’s complex legacy

The book gave a child’s face to the incomprehensible truths of the Holocaust. In part because it became required reading at many schools, it often constituted what the U.S. Holocaust Museum and Memorial calls “the first, and sometimes only, exposure many people have to the history of the Holocaust.”

But its popularity, and durability, masked many of the Holocaust’s harsh realities. The diary ends before the family’s arrest, sparing readers most of the details of what happened to Anne after her capture. The Franks also had more space, stability, and support than most of the 28,000 Dutch Jews who went into hiding during the war. And her words are often misquoted or taken out of context.

In the diary’s most famous and most quoted passage, Anne wrote about her belief that “people are really good at heart.” But in much of her diary, she documented a grim view on humanity and gave voice to the harrowing anxiety of war and persecution.

“I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death,” she wrote immediately after her most famous line. “I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us, too.”

Protecting Anne’s legacy

Anne’s diary helped the world learn about the horrors of the Nazi genocide of European Jews. But it also put heavy symbolic weight on the shoulders of a murdered 15-year-old who could no longer speak for herself.

“Few other writers have given rise to such intense emotion, such fierce possessiveness, so many arguments about who is entitled to speak in her name, and about what her book does, and doesn’t represent,” writes author Francine Prose.

Those battles have played out in controversies over the authenticity and legitimacy of the work itself. Despite multiple comprehensive forensic investigations that have proven Anne Frank wrote the diary, false claims that it is a forgery continue to fuel Holocaust denial. There have also been tussles over who owns Anne’s legacy—including legal battles between the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, which preserves the secret annex site as a museum, and the Anne Frank Fonds, a foundation set up by Otto Frank that owns the rights to the text.

Who betrayed Anne Frank?

The fate of the Franks and their compatriots has also fueled an ongoing interest in who betrayed them to Dutch officials in 1945. Over the years, several potential culprits have been named. In 2022, one analysis pointed the finger at Jewish notary Arnold van der Bergh, whom an anonymous tipster accused of reporting the hiding place to the authorities. Others, including the director of the Anne Frank House, are unconvinced van der Bergh was the betrayer.

(How a cold case team searched for Anne Frank's betrayer.)

Ultimately, though, the power of Anne Frank’s story lies in its most frustrating quality: that it is unfinished. Anne’s abbreviated diary, her tragically short life, and the lack of consensus on her betrayal after more than 80 years all speak to the magnitude and the cruelty of the genocide she has come to represent.

And yet her words, penned in secret in the face of grave danger, persist. “No one knows Anne’s better side,” she wrote in her diary’s final entry. Decades after her death, we do.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital