3D scans reveal largest cave art in North America

The larger-than-life composition is mostly invisible to the naked eye. Advanced technology helped uncover the stunning composition.

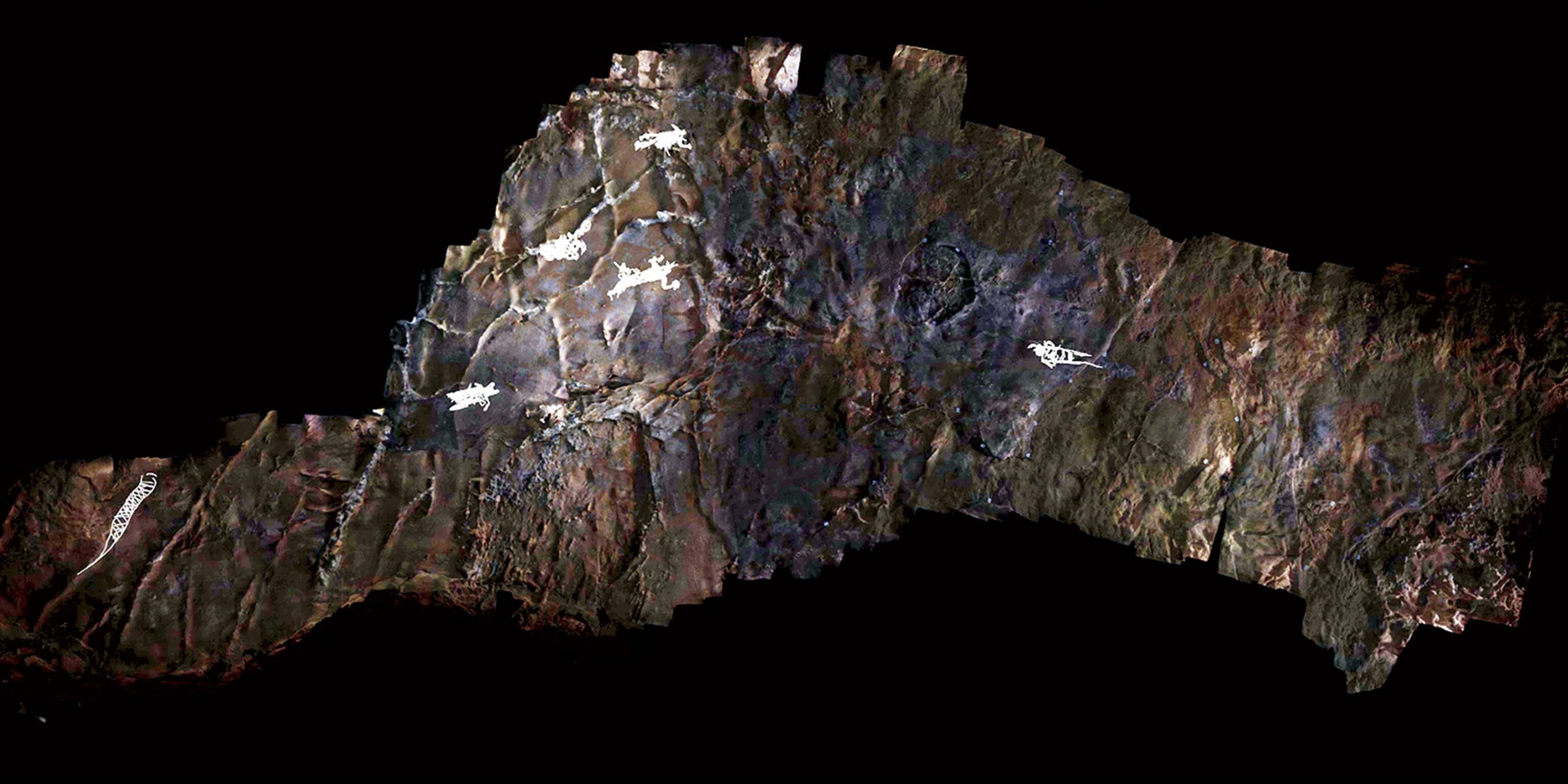

Deep in the dark recesses of a limestone cave in Alabama soar life-sized figures that span earthly and spiritual realms. Traced into the mud of the cave ceiling by torchlight more than a thousand years ago, the sprawling scene is so enormous and faint it cannot be discerned by the naked eye—yet the ancient etchings are being celebrated as one of the largest rock-art creations in all of North America, and the largest to ever be discovered in a cave.

In a study published today in the journal Antiquity, researchers describe how they used a process known as 3D photogrammetry, originally developed to capture vast expanses of Earth via aerial photos, to uncover the enigmatic images sheltered in an underground system in the Southeast United States known prosaically as “19th Unnamed Cave.” Its location is shielded to prevent looters and casual cavers who could damage or destroy the ancient artwork for profit or by mistake.

Jan Simek, an archaeologist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the paper’s first author, had been inside 19th Unnamed Cave before. In the first study of the karst cave in 1998, Simek and his co-author on the current paper, Alan Cressler, described its glyph-covered ceilings as “the southernmost manifestation of what we now recognize as a widespread prehistoric artistic tradition” across North America before the arrival of European colonizers.

Now, with the help of a 3D model, they’ve discovered even more art in 19th Unnamed Cave—this time, images that are all but invisible to the naked eye, in a place never thought to be home to life-sized rock art. Over 5,000 square feet in size, the cave chamber height is so low that modern cavers must squat—or lie down—to see it. Its ancient creators must have once done the same.

“There are thousands and thousands of engravings” on the cave ceiling, says photographer and co-author Stephen Alvarez.

And if that’s the case in one Alabama cave, the researchers say, it could be true in many more.

'Those who had been there before'

Traced in the mud ceiling of the cave by intrepid artists and preserved for a millennium before being discovered, the massive etchings were created—and discovered—in an unforgiving setting.

A foremost expert on Southeastern cave art, Simek is fully aware of the many inconveniences at 19th Unnamed Cave: three miles of damp, dark corridors, with much of the visible cave art concentrated on the ceilings of passages barely two feet high.

Cave environments “can be very unpleasant,” Simek admits. “You go to caves not because you like caves, but because that’s where the stuff is.”

Co-author Alvarez has also made caving his career. A frequent contributor to National Geographic, he’s the founder of the Ancient Art Archive, a non-profit devoted to using cutting-edge technology to preserve ancient art.

“I used to like exploring the biggest caves in the world because I wanted to be the first person to go there,” says Alvarez, who grew up exploring Tennessee’s many caverns. Once he encountered prehistoric cave art, though, “I became much more interested in who had been there before.”

The researchers discovered the ancient masterpieces thanks to 3D photogrammetry, an emerging technology that creates three-dimensional models based on overlapping photographs. Mapmakers have used the technology for years, taking advantage of overlapping aerial photography to infer physical features of the Earth below and create topographic maps.

But you don’t have to be in a plane to produce photogrammetry. With the right equipment, the right team, and a lot of patience, it can also be done deep underground.

With a digital camera, LED lights, and a photo rig alternatively set up on the dry cave floor or in patches of knee-deep water, the team spent two months underground capturing every inch of the ceiling of the main chamber in 19th Unnamed Cave—16,000 images in all.

Much of the real work, however, was yet to come, and required uploading and processing each 50-megapixel photo into a larger 3D model. (The sheer amount of data “melted our first computer,” Alvarez says.)

As the photos were layered together and the program extrapolated a digital model of the cave ceiling, the researchers would gather to take a look, eager to spot details that were too large or too faint for them to discern using either their own eyes or standard photographs of the space.

“I was trying to show Jan a new snake figure I had discovered, when he said, ‘What about the great big guy right there?’” Alvarez recalls.

“Big” was an understatement: The figures that began to emerge from the photographs, some etched so finely they were invisible to the naked eye, were life-sized. The largest, a snakelike figure bearing the distinctive marks of an eastern diamondback rattlesnake—a powerful symbol in Indigenous traditions of the Southeast—was more than 11 feet long. The team says it is the largest known piece of cave art in North America, and comparable in size to rock art never thought to exist beyond the American Southwest.

‘Spirit creatures with human characteristics’

Other glyphs—the paper describes the five largest— are shorter, but no less compelling, and portray human figures that appear to sport ceremonial regalia.

The glyphs are so different from other, more familiar figures that Simek has seen in nearby caves he’s careful about ascribing meaning or intention to the ancient art works. At the same time, the archaeologist says, the “spirit creatures with human characteristics” have parallels with other rock art in the Southeast and elsewhere across America.

“People ‘mapped’ their conceptual universe onto the natural world in which they lived,” Simek writes, turning physical caves into a powerful representation of the underworlds of their belief system.

With the help of torches and tools, the artists seem to have deliberately designed—and skillfully executed—the figures. Unlike cave art in places like Chauvet Cave in France, the artists didn’t rely on mineral pigments. They would likely have scratched them into the mud roof with either tools or their fingers while crouching or lying down in the low-ceilinged chamber.

“Think about doing that by torchlight,” says Alvarez. “You would only have one shot at it. Maybe the making of the art is as important as the art itself.”

Though the researchers can only speculate about the specifics of the cave artists’ techniques or beliefs, they know plenty about life in what is now Alabama during the Woodland period between about B.C. 1000 B.C.E. and 1000 A.D. An analysis of pottery sherds as well as radiocarbon dating of charcoal and a torch inside the cave—funded in part by the National Geographic Society—place the creation of the artwork to somewhere between the second and tenth centuries A.D.

At the time, the area’s Indigenous residents were engaged in a long-term process of domestication, taming and farming crops like sunflowers and maygrass. Those innovations ushered in a “period of significant economic and social change,” says Simek.

The presence of massive rock art in the Southeast “just emphasizes that ideas are flowing back and forth across this continent before European contact,” says Alvarez. The find challenges notions that large figures were only depicted further west in places like Utah, Texas, or Baja California.

The research also raises questions about when exactly an archaeologist’s work is done. In the world underground, the study suggests, there’s plenty left to find—and even sites that already have been considered may be candidates for photogrammetry studies that could reveal as-yet unseen artifacts.

Perhaps, says Simek, the art in 19th Unnamed Cave is more common than we realize, and we simply haven’t figured out the right way to look for it. But, he adds, researchers looking for other ancient artwork are racing both against the natural erosion of these delicate environments and the actions of other humans.

“All you have to do is touch the ceiling and it’s gone,” says Alvarez.

Even more complicated is the tangle of issues raised by the locations of the caves themselves. Many across the U.S. are situated on private property and owned by people who lack the financial resources and security necessary to properly preserve and maintain the cave art. And, Simek says, “We have one of the most ineffective heritage protection programs of any civilized country on the planet.”

Southeastern archaeologists have attempted to counter that, starting with the cave’s name—anonymized to keep would-be lookers (or looters) out of the cave.

“We never give cave locations,” Simek and Cressler wrote in a paper delivered at a cave management symposium in 1999. “And we never confirm or deny the guesses made by archaeologists and cavers.”

So what can the researchers confirm about the mysterious cave and the equally enigmatic figures etched within?

“It will take years for people to sort out what’s on those ceilings,” says Alvarez. “When I think of the totality of the engravings on that quarter-acre ceiling, it’s right up there with the most incredible things I’ve ever seen.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

Environment

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- When America's first ladies brought séances to the White HouseWhen America's first ladies brought séances to the White House

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

Travel

- This striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotelsThis striking city is home to some of Spain's most stylish hotels

- Photo story: a water-borne adventure into fragile AntarcticaPhoto story: a water-borne adventure into fragile Antarctica

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramid