How Madame Tussaud built her house of wax

After surviving the horrors of the French Revolution, Marie Tussaud went on to captivate Britain with her wax figures.

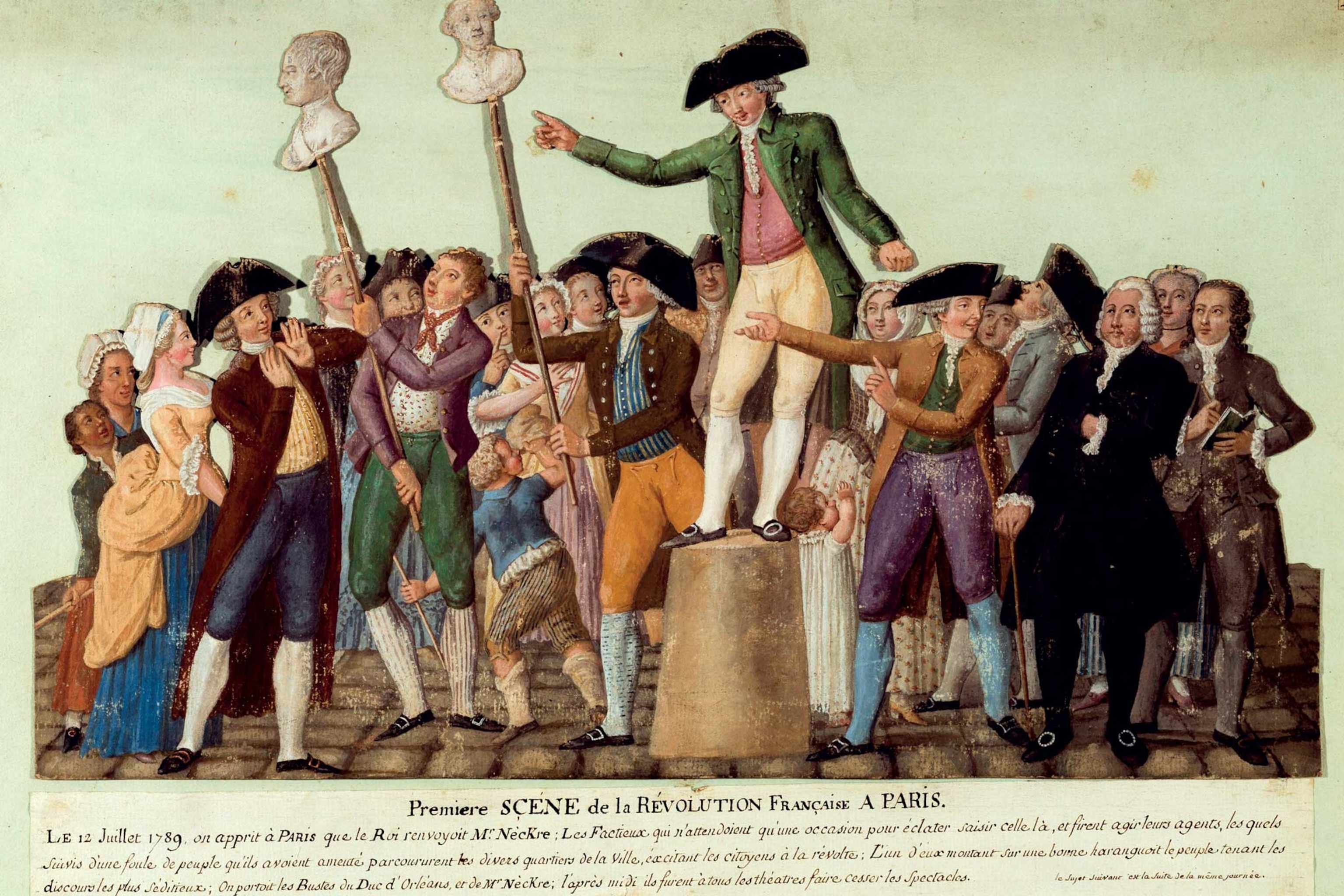

Paris seethed with tension in the summer of 1789 as crisis engulfed France. Gripped with revolutionary fervor, the people were clamoring for a greater say in their government. In July outrage grew after King Louis XVI fired his reform-minded finance minister, Jacques Necker. A huge crowd of revolutionaries took to the streets of the capital, waving black flags and mimicking a funeral cortège. They bore wax effigies of both Necker and the pro-democracy prince, the Duke of Orléans. Taken from the collection of a well-known waxwork artist, these likenesses may have been sculpted by his apprentice, Marie Grosholtz, who would become better known by her married name: Madame Tussaud.

Years later, Marie sculpted a new collection of waxworks inspired by the horrors of the French Revolution that she had witnessed. These figures captured the public imagination and became the foundation of an empire. Blending the famous with the grotesque, today Madame Tussauds wax museums can be found in cities all around the world, inspiring the same fascination of seeing celebrities rendered in wax as they did in England in the 19th century.

Molding of Madame

Much of what is known of Madame Tussaud’s early life comes from her memoirs, which she dictated to a friend, Francis Hervé, when she was in her late 70s. The work is full of colorful details and anecdotes, some of which were never verified. Tussaud was very conscious of her image, which she carefully cultivated over the years, and may have embellished. Hervé generously attributed this tendency to her advanced age which led to “recollections [that] must sometimes be in a degree confused and impaired.”

Madame Tussaud was born Marie Grosholtz in Strasbourg, eastern France, in 1761, months after her father was killed in the Seven Years’ War. Her early childhood was spent in the Swiss city of Bern, where her mother worked as housekeeper to the anatomist and wax modeler Dr. Philippe Curtius.

Having abandoned medicine to pursue his art full time, Curtius moved to Paris in 1765, and two years later, little Marie and her mother joined him. In the absence of a father, Curtius acted as guardian to the little girl, and she regarded him like an uncle. Curtius’s waxworks had built a considerable following, and his first exhibition in 1770 grew so successful that it was moved to the royal palace in 1776.

Curtius taught Marie how to make wax sculptures. She was 15 or 16 when she created her first figure, a likeness of the philosopher Voltaire. She followed it with waxworks of other famous figures, such as the Romantic philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who would inspire the leaders of the French Revolution, and the American patriot Benjamin Franklin. She later wrote in her memoirs how both were regular guests at Curtius’s Paris home.

In 1782 Curtius unveiled a second exhibition of celebrity busts on the Boulevard du Temple. It included a Caverne des Grands Voleurs (Cavern of the Great Thieves), featuring sculptures of criminals, some whose corpses were delivered to Curtius following execution so that he could capture their likenesses. An observant student, Marie would later use this idea for her own Chamber of Horrors.

Keeping Her Head

In her memoirs Madame Tussaud recounted how, around 1780, she became a favorite at the palace of Versailles and taught modeling to Madame Elizabeth, the king’s sister. When revolution broke out in 1789, Marie and her mentor, both accused of having monarchist sympathies, found themselves in danger. Curtius, as a good businessman, knew that the best way to survive was to adapt his waxwork collection to the quickly changing times. Revolutionary leaders and those sent to the guillotine became the new stars of his gallery.

Marie recalled how during the Reign of Terror that lasted from the fall of 1793 to the summer of 1794, she was arrested, together with Joséphine de Beauharnais, the future wife of Napoleon. She went as far as having her head shaved in preparation for execution. In return for clemency, both she and Curtius are said to have taken on a gruesome task—sculpting death masks of the executed.

There is, in fact, little evidence outside Tussaud’s own account that she directly sculpted masks of the freshly guillotined king or the assassinated revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, although models of these figures did find their way into Curtius’s collection. Despite the uncertainty, the notion of Tussaud undertaking such grisly work became one of the most famous aspects of her life story. As the English poet Hilaire Belloc wrote with wonder: “The hand that modeled Marat was a hand of Marat’s age. It touched the flesh of the dead man.”

Fame and Fortune

Philippe Curtius died in September 1794 and left Marie the sole heir of his waxwork museums. A year later Marie married François Tussaud, an engineer, and later had two sons, Joseph in 1798 and François in 1800.

The marriage grew strained, and times were hard, and Tussaud’s waxworks business was almost ruined by the ravages of revolution. The Madame Tussauds empire might well have never begun had she not met the German illusionist Paul Philidor. A pioneer in the use of the “magic lantern,” which projected colored slides of ghosts and ghouls, Philidor mounted elaborate spectacles known as phantasmagoria. The public was ripe for this kind of new sensory experience and clamored for more.

Philidor suggested to Tussaud that they combine his projections with her wax figures to create a joint show for the Lyceum Theater in London. She agreed, and in 1802 traveled to England, to try her luck in a land untouched by turmoil. She was, however, disappointed with the show, complaining that Philidor was failing to promote her startling, lifelike figures. Toughened by the years of danger and revolution in France, this slightly built woman, now in her 40s, decided to go into business for herself and strike out alone in a new country.

Loading her precious waxworks into rail carriages, Madame Tussaud set off on a touring exhibition around the British Isles that would last, on and off, for a period of nearly 30 years. Free of Philidor and relying on her own entrepreneurial instincts, Tussaud met with instant fame. The French Revolution and the Reign of Terror awoke fascination, repugnance, and pity in the British, and Tussaud’s creations—Marat stabbed in his bath, the doomed King Louis, and even a model of a guillotine—brought her public face-to-face with the 19th-century equivalent of virtual reality.

In every city Madame Tussaud found sumptuous salons where her waxworks were put on display. The exhibits attracted paying visitors at a time when public exhibitions of this kind were rarely found outside London. The tours were very popular and profitable. Although Tussaud was estranged from her husband, she still sent money to him and their younger son François in Paris.

She learned, however, that her husband was squandering all the money she sent, to the point that François was later forced to sell the part of the waxwork collection that remained in Paris. In 1822 young François came to London for good, joining his mother and brother Joseph. A trained carpenter, François was a good fit in the family business, carving wooden arms and legs for his mother’s wax figures. From this point, the exhibition was renamed and became known as Madame Tussaud and Sons.

A Legacy in Likenesses

In 1835 Marie and her sons gave the collection a home in London on Baker Street. By then, executions were no longer public and the so-called Separate Room—later dubbed the Chamber of Horrors by the satirical magazine Punch—offered a tantalizing, if simulated, alternative for ghoulish Londoners. The popularity of the museum was given an extra boost in 1837 when young Queen Victoria allowed her likeness to be fashioned. The resulting waxwork was dressed in an exact replica of her coronation attire and became the exhibition centerpiece.

The quiet Frenchwoman, who nevertheless is said to have made death masks from executed London criminals, died in her sleep in April 1850 at age 88. Her sons and grandsons carried on the business. In 1884 her grandson Joseph moved the exhibition to a larger space in Marylebone Road. Although a fire in 1925 and aerial bombing during World War II caused serious damage to the collection, some of the original figures were spared.

Madame Tussauds has become a global brand, one of the most visited attractions in London, with 24 branches across the world, including seven in the United States. In 2016, following complaints by visitors, the Chamber of Horrors in London was closed. Inspired by the crowds who came to see the model of Queen Victoria in the 1830s, Marie Tussaud’s successors have tirelessly produced figures to cater to the public demand for famous figures, recently modeling actor Eddie Redmayne and Prince Harry’s bride, Meghan, Duchess of Sussex. Even if the ghoulish side of her work is waning in popularity, Marie Tussaud’s instinct for celebrity is still proving a winning ticket.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital