The roller-skating revolution swept the world in the 1800s

Invented in the 1700s, roller skates became a huge fad after an 1863 innovation made them easier to control. It sparked the first (of many) skating crazes.

During the 2020 pandemic, roller-skating made a big comeback, as people looked for safe ways to have fun during quarantine. This pastime may seem like a quintessentially 20th-century phenomenon, but wheeled shoes first rolled out as early as the 1700s. As models changed and improved over the years, skating fads bloomed in Europe and the United States throughout the 19th century.

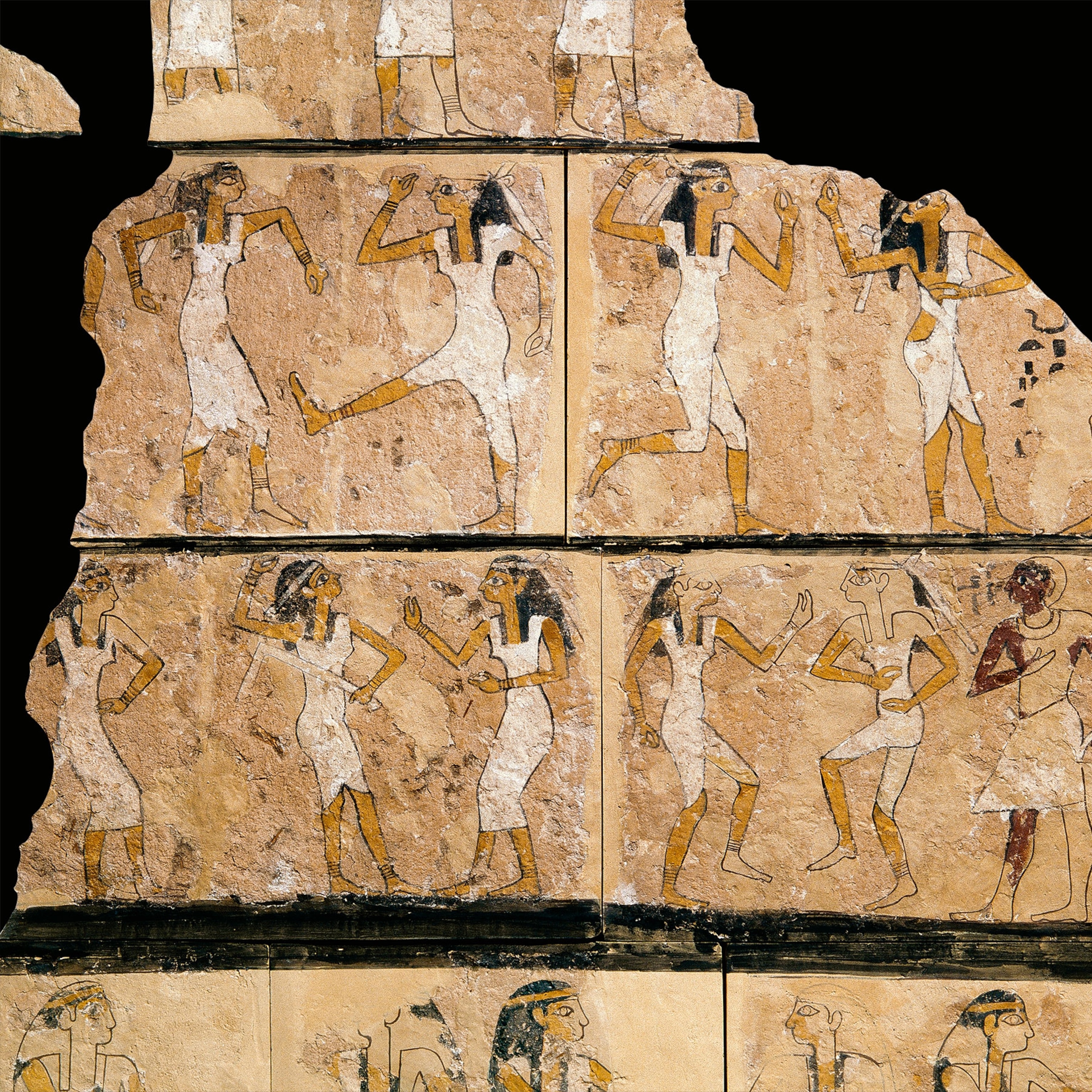

The precursor to roller-skating— ice-skating—is vastly older and can be dated as far back as 1800 B.C. Archaeologists found evidence that people in Scandinavia fashioned ice skates from animal bones, pioneering the oldest human powered means of transport. (What does 'skating on thin ice' sound like?)

In-line adventures

One of the first recorded attempts to put wheels on shoes took place in the 1700s. An unnamed Dutchman strapped to his shoes strips of wood with wooden spools on the bottom, known as “skeelers.” They quickly broke.

Another famous early attempt to skate on wheels was made by an eccentric Belgian inventor, John Joseph Merlin. Merlin’s invention featured metal wheels arranged in a line, like the blade of an ice skate, on the bottom of a wooden sole. (Here's the science behind ice-skating.)

Renowned for his museum of clocks, musical instruments, and automatons, Merlin lived in London where he was a favorite at high society parties. At a masquerade ball in 1760, he reportedly played a violin as he attempted to glide around on roller skates. Unable to control his speed or direction, he crashed into a large mirror and shattered it. The violin was destroyed, and Merlin was injured.

Another Belgian inventor took a crack at roller skates around 1790. While living in Paris, Maximiliaan Lodewijk van Lede attached wooden wheels to an iron sole plate and dubbed it the patin à terre, or land skate. Van Lede’s work did not get much attention, perhaps because he had to flee Paris during the French Revolution and leave behind his invention.

The first patented roller skate was designed by French inventor C.L. Petibled. His skate was a wooden sole with three wheels attached in a line. Straps held the skates to people’s feet. Four years later, Robert John Tyers received the first English roller skate patent. His “Volito” sported a row of five wheels, with slightly larger center wheels to enable maneuvering by shifting weight to the front or rear. The Frenchman Jean Garcin used the same idea with his three-wheeled skate in 1828. These early skates were not very maneuverable. Despite improvements made to the design, it was difficult to do anything other than travel in straight lines or turn in wide circles.

Parisian inventor Louis Legrand was the first to rethink the in-line approach, designing the so-called quad skates which had four wheels attached in two rows at the heel and the ball of the foot. Legrand skates were used in the 1849 production of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Le Prophète at the Paris Opera, creating a major sensation. A later performance at London’s Covent Garden boosted their popularity even further.

Legrand’s skate was the precursor to what became the standard design for roller skates for decades. Developed by an American inventor, James Leonard Plimpton, this four-wheeled design made roller-skating easier and more fun. The owner of a machinery factory in New York, Plimpton was advised by his doctor to take up ice-skating to improve his health. To skate in warmer weather, he invented a roller skate that could be used in all seasons. (Chocolate sparked a sweet craze in Europe.)

Patented in 1863, his two-by-two “rocker skate” allowed the wheels to move independently of the sole, which made for easier navigation and turning. Each pair of wheels was attached to a pivot with a rubber cushion, which allowed the skate to rock and required that skaters only shift their weight to turn.

Writing more than a decade after the invention of the Plimpton skate, the British literary weekly All the Year Round said, “[T]he immense superiority of those skates over everything invented up to the present time has induced wholesale piracy.” With various improvements, this basic model would stay the most popular roller skate for more than a century.

Skating crazes

Plimpton’s skates made skating so easy that they sparked the first roller-skating craze among young people. Starting in the 1860s, roller rinks began to pop up in large towns and cities across western Europe and the United States, where the first public roller rink opened in 1866 in the Atlantic House, a seaside resort in Newport, Rhode Island.

To encourage the perception of roller-skating as a refined pastime, Plimpton promoted the sport as a “proper” activity for ladies and young gentlemen, rather than for the masses. With a live orchestra and then-uncommon electric lights, skating rinks became the perfect place to see and be seen in the latest fin de siècle fashions. The rinks became so popular that they competed with ballrooms. In 1876 Le Monde Illustré spoke of the “delirium on wheels” that gripped Paris, while the London press dubbed the new devotees of roller-skating “rinkomaniacs” and “rinkualists.”

The medical profession felt compelled to evaluate the effects of roller-skating. In 1885 Scientific American concluded that “the pathological outcome” was small in proportion to the number of people who had “engaged in propulsive divagations upon polished floors.” (Here's how California skateboarding revolutionized global culture.)

Hell on wheels?

In the United States the roller-skating craze of the 1880s was both embraced and feared. Public rinks had begun appearing in cities like New York since the 1860s. By the 1880s the craze had even spread to the West. In 1885 McCarty’s Rink opened in Dodge City, Kansas (it also doubled as an opera house). Older generations grew concerned about roller-skating’s effects on young people’s morality. In an 1885 article in the Carlisle Weekly Heraldin Pennsylvania, some preachers called skating rinks “pits of perdition.” A satirical cartoon even suggested that pastors incorporate skating into their sermons to attract more congregants.

During this period, roller-skating began to be recommended as an alternative form of urban transportation in Britain, where London businessmen and even ladies could be seen roller-skating to work. The sport of roller polo, an early version of roller hockey, emerged in both the United States and England, and other organized events such as dance skating competitions and speed contests developed around the same time.

By 1880 London was said to have had 70 roller rinks; Paris had 40; New York City at least 20. No major town was without one. At the turn of the 20th century, huge rinks were built in the Chicago Coliseum and New York City’s Madison Square Garden, signaling the pinnacle of the first roller-skating craze. Roller-skating’s popularity waxed and waned in the coming decades, going through numerous up-and-down cycles. During the Edwardian era and the Roaring Twenties, young people flocked to roller rinks to skate and flirt. Skating even began showing up on silent movie screens, including Charlie Chaplin’s 1916 film The Rink.

Families were also catching on to the roller-skating phenomenon for outdoor recreation. As many dirt roads were paved, skating’s popularity could spread beyond cities. Children skating into town became commonplace, along with complaints from older generations about disregard of street laws and dangerous maneuvers. Unsurprisingly, skating injuries shot up.

After the Great Depression and World War II, roller-skating entered a “golden age” in the United States, where it became the biggest participation sport. At its peak, there were some 5,000 rinks and 18 million skaters. Fans flocked to watch Roller Derby: In the late 1940s full-contact matches began to be televised every week. (Watch: This roller derby girl squad is the first of its kind.)

Improving designs

Over the years, innovators sought to improve the quad skate, adding ball bearings to wheel construction in the 1880s, which made for a smoother ride. Attempts at competing with the basic quad design, however, failed to catch on. Englishman J. F. Walters’ 1882 three-wheeled skate, inspired by the tricycle, or the Parisian Charles Choubersky’s 1896 bicycle skate, featuring two small bicycle wheels, proved unsuccessful.

Other roller skate innovations did catch on by improving skaters’ ability to turn and control their speed. The standardization of toe stops in the mid-20th century, made slowing down and stopping much easier. Wooden wheels eventually gave way to metal and rubber. When polyurethane wheels became the standard, traction improved, and the roller-disco craze exploded in the 1970s. (See how bicycles also tranformed our world.)

In the 1980s a return to the in-line skating model sparked another craze. Two ice hockey–playing brothers designed an in-line skate to mimic the action of their ice hockey skates. Their invention, which they dubbed the Rollerblade, drove a skating resurgence centered on athletics. In-line skating competitions and roller hockey surged in popularity.

Throughout its nearly three centuries of history, skating has remained a source of exercise and entertainment. While the design and materials are sure to evolve, its appeal will remain much as it did 150 years ago.