Ball python exports raise concerns as demand for the popular pet grows

Though widely bred in captivity in the U.S. and Europe, tens of thousands are exported from West Africa each year, with little understanding of what that means for their conservation or well-being.

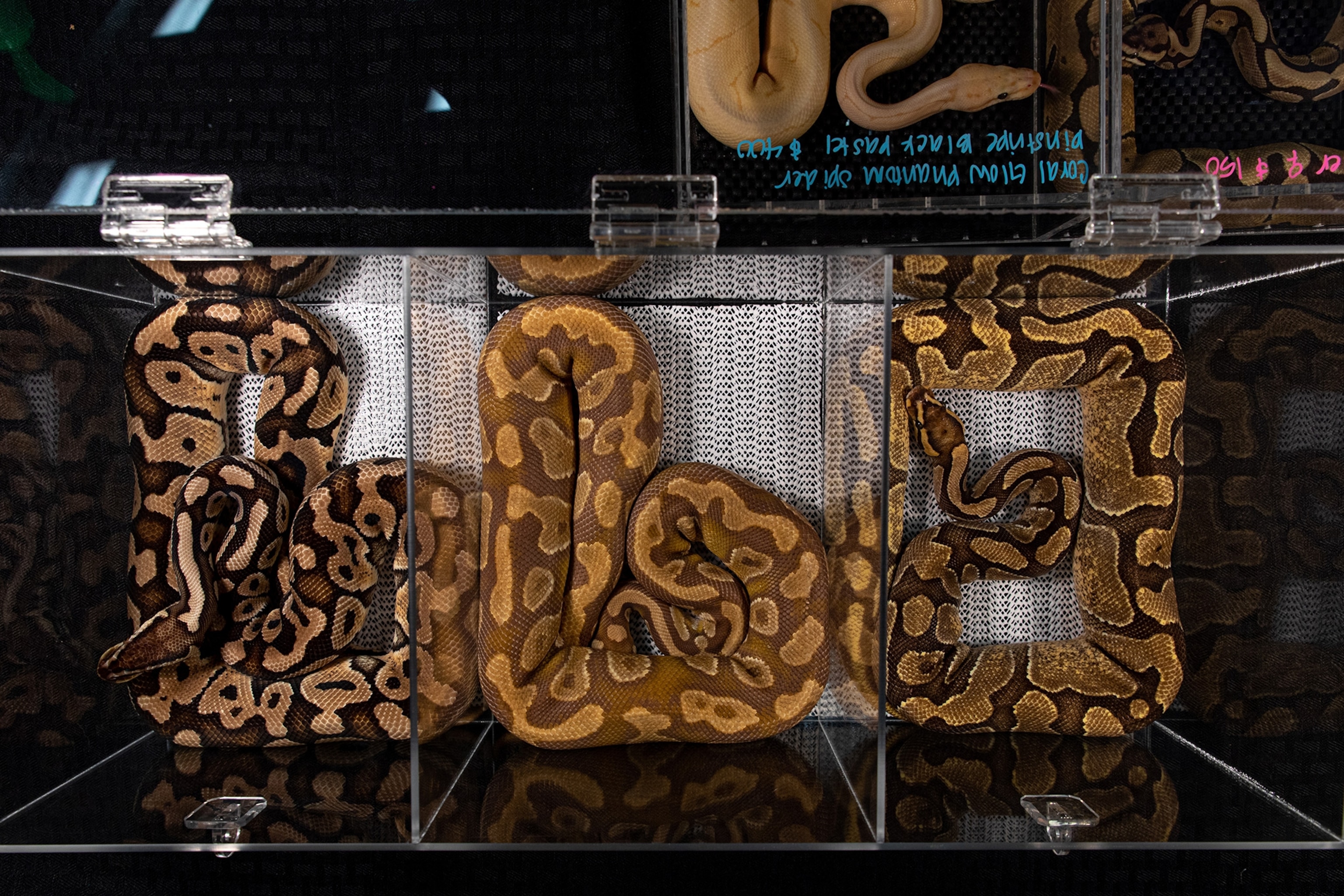

Even if you’re not a snake person, once you meet a ball python, there’s a good chance it’ll grow on you. They’re smooth and sleek. They’re a deep ebony or chocolate color with golden-brown markings. They’re gentle and meek, and when they’re afraid, they curl into a ball, tucking their head in the middle.

Ball pythons, which live primarily in West and central Africa, have grown on a lot of people—they’re believed to be the most popular pet snake in North America and Europe. About 800,000 U.S. households are estimated to keep snakes, based on the National Pet Owners Survey, though it’s not known how many of those are ball pythons.

From 1997 to 2018, more than 3.6 million ball pythons were exported legally from West Africa. Togo—the leading supplier—along with Benin and Ghana account for more than 98 percent of exports, according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the treaty that regulates cross-border trade in wildlife.

Despite the magnitude of the international trade, scant information exists on how many ball pythons are in the wild or how trade is affecting wild populations, which also face significant pressure from hunting for bushmeat, as well as from use in traditional medicines and other threats. Ball pythons aren’t classified as threatened with extinction, but a collection of new research suggests that perhaps they should be: It points to gaps in oversight of the supply chain in West Africa and raises questions about whether ball pythons should have more protections than they do now.

During the 1980s and early ’90s, ball pythons were seen as cheap and commonplace pet snakes, says Dave Barker, a trained biologist who with his wife, Stacy, started one of the first major captive-breeding ball python businesses. Then in 1992, the first “designer” ball pythons—albinos bred in captivity—went on sale. Suddenly the species “came from the back seat of the car to the driver’s seat,” Barker says. Demand exploded for ball pythons, which are now bred in dazzling colors and patterns.

Although commercial-scale captive breeding of these snakes has been established for several decades, ball pythons are also still the most common CITES-protected species exported live from Africa because they’re cheaper than their captive-bred counterparts. Under CITES rules, countries set annual caps, or quotas, for the number they can export legally, and trade should be allowed only if there’s scientific evidence showing that it won’t undermine wild populations. Togo, for example, has an annual export quota of 1,500 wild ball pythons and 62,500 “ranched” ones, raised from an egg or an egg-carrying female taken from the wild.

Neil D’Cruze, who has a Ph.D. in herpetology, is the global head of wildlife research for the advocacy group World Animal Protection, as well as a visiting researcher with Oxford WildCRU, a conservation research project at the University of Oxford, in England. Two years ago, he got curious about the trade in ball pythons.

“As somebody who loves reptiles and has spent many [thousands of] hours studying them, I get why you’d want to own one,” he says. But when he examined the trade data, he says the export numbers jumped off the page, leading him to wonder what’s being done to ensure that the trade isn’t a risk in terms of animal welfare, human health, and conservation.

D’Cruze and an international, interdisciplinary team of scientists with expertise ranging from the socioeconomics of wildlife trade to python husbandry, genetics, welfare, pathology, and more studied the ball python trade, supported with grants from World Animal Protection. Now, in a series of five recently published scientific articles and three more to be published soon, the findings are being made public.

Together, the research suggests that after several decades of high exports and weak oversight, a lack of reliable data means it’s nearly impossible to make educated, science-based decisions about how to manage and protect wild populations of ball pythons. In particular, the researchers call into the question the suitability of Togo’s export quota.

A report published March 23 by World Animal Protection calls for drastic change: suspending the global trade in ball pythons. The research papers, however, which are published in open-source, peer-reviewed journals, make more moderate recommendations, particularly for Togo. Among them is a call to reduce the number of ball pythons that can be exported from there and to strengthen oversight of collection in the wild, ranching, and welfare standards.

Importers in the U.S. say trade in ball pythons from West Africa is good for conservation—that by placing a value on the snakes, those who live alongside them in Africa have an incentive to make sure they don’t disappear. “It’s sustainability through commercialization,” says Michael Van Nostrand, the owner of the Florida-based reptile business Strictly Reptiles. His company imports more than 10,000 ball pythons a year from Togo, according to import records from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service obtained by World Animal Protection. “Of course the pet trade is taking some,” he says, “but that’s what the quota system is for.”

‘Warning flag’

To glean more information about the sustainability of the ball python trade from Togo, the researchers interviewed 57 Togolese snake hunters who supply export facilities. Three-quarters of them said they see fewer ball pythons today than five years ago.

“That’s a warning flag,” D’Cruze says.

It will take more research to determine how much of the decline the Togolese hunters perceived is a result of collection for the pet trade rather than other pressures, according to the scientific paper analyzing the hunter interviews. But these interviews—combined with other findings from the project’s research—raise questions about whether Togo’s export quotas are based on strong ecological science and regulatory oversight, as CITES requires.

“There are enough red flags at the moment to severely reduce the activity,” D’Cruze says of the trade.

Zoologist Gabriel Segniagbeto, of the University of Lomé, is Togo’s scientific authority for CITES. His job is to advise the government on how trade will affect species in the wild and provide the rationale to help set export quotas. He’s also a co-author of several of the ball python project’s published papers. He admits that the hunters’ information is concerning, but he doesn’t think it’s necessary to reduce Togo’s export quota yet. Instead, he supports a monitoring program for hunting and ranching practices. “The python trade has economic value for the hunters,” he says, so their livelihoods must be protected.

Mike Layman, whose Florida-based reptile breeding and importing company, Gourmet Rodents, imports several thousand ball pythons a year, says focusing on the responsible trade of any species is key. “Whatever the responsible use of that resource is might not be the same today as it is tomorrow—it’s something that continues to need review," he says. In addition to feeling a sense of responsibility to the animals, he says, sustainable trade is important for importers’ companies: If a population crashes, their businesses suffer.

The trade in West African ball pythons is important, according to Eric Fouchard—who says his facility in Lomé, Toganim, produces about 45 percent of Togo’s ranched ball python exports—because it prevents people from collecting them for bushmeat markets instead. The pet trade is “teaching our people that a live animal is more profitable than a dead one,” he said in an email. (None of Togo's other ranching facilities contacted by National Geographic responded to requests for comment.)

This argument, presented by several people involved in the pet trade interviewed for this story, is based on an untested assumption, D’Cruze counters. “Until we have the evidence that the pet trade is a vital tool for [ball python] survival,” he says, “I’d prefer us to err on the side of caution” by reducing or stopping the trade.

A long journey

Ball python ranching begins with rural hunters who bring wild-collected eggs and egg-carrying females to ranching facilities. The facilities hatch the eggs and raise the young ball pythons until they’re old enough to be exported—anywhere from a few days to several weeks. To offset the impact of taking eggs from the wild, the practice in Togo has been to return previously pregnant females and a proportion of the young snakes to the wild.

When the exported ball pythons arrive in the U.S., they may be inspected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to make sure that the contents in the shipment match the paperwork. The goal is to ensure that there’s no smuggling of undeclared species, says Eva Lara, a regional supervising inspector with the service, and that shipping guidelines for animal welfare set by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) are met. (The Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t have the resources to inspect every wildlife import, but live, CITES-listed shipments are a priority, Lara says.) Then the snakes are claimed by the importers. They may be sold to a wholesaler, reptile seller, pet store, or directly to a buyer.

How many ball pythons die in intercontinental transit has not been studied, but estimates for reptiles in the international trade suggest up to about 5 percent—possibly equating to thousands of ball pythons a year. Gourmet Rodents’ Layman puts the mortality rate of his ball python imports in 2019 at just over one percent.

The shipping process can be stressful for the pythons, says Mike Corcoran, a practicing veterinarian and president of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians. They’re adapted to live in hot, humid environments, which may be difficult to maintain during a long transport, he says.

Most snakes do survive international shipping, but D’Cruze says mere survival isn’t good enough. “An animal’s ability to tolerate and survive is independent of its ability to suffer,” he says.

Stressed animals are also more likely to get sick. “Once they enter the trade, you should consider them immunosuppressed at least for a certain period, and they are prone to any disease that ball pythons can get,” says Tom Hellebuyck, a veterinarian and wildlife pathology researcher at the University of Ghent, in Belgium.

Preventing disease

Diseases aren’t only a possible problem for ball pythons but also potentially for humans. Wild animals of all types can be hosts for a number of pathogens, as has become clear with the COVID-19 pandemic, a zoonotic disease believed to have originated in bats. Snakes and other reptiles, for example, are known to carry strains of salmonella, West Nile virus, and tick-borne diseases, Hellebuyck says.

A 2017 outbreak of salmonella in the U.S. was traced to ball pythons, sickening several children. Many healthy reptiles carry salmonella, which is why the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children less than five years old and immunosuppressed individuals not have contact with them.

D’Cruze and his colleagues combed existing scientific research to identify more than 150 different pathogens that could be carried by ball pythons. They then took swabs at reptile farms in Togo and tested them for pathogenic bacteria. The paper detailing the results has been accepted by a journal, has completed peer-review, and is expected to be published soon. D’Cruze says none of the animals were “in hygienic and safe conditions….There is definitely evidence of pathogenic bacteria that is cause for concern.” Fouchard, who has not seen paper, says the samples taken at Toganim were from a small number of animals and are not representative of his facility.

There’s also the possibility of novel pathogens. “Any animal coming from its native habitat could be coming with an entire suite of potential pathogens that we have no idea about,” says Brian Bird, a virologist at the University of California, Davis, who’s part of the PREDICT Project, which monitors for viruses with the potential to jump from animals to humans. For any trade in wild animals, he says, there’s the risk of introducing the next SARS- or COVID-19-causing virus to humans or of introducing the next chytrid fungus (a problem now ravaging amphibians around the world) to snakes in other regions.

Wildlife inspectors will interdict a shipment with a sick or injured snake only if the problem seems to have resulted from a violation of IATA welfare standards, Lara says. If a snake appears visibly sick—unresponsive, limp, or showing mucous, for example—and no IATA violations were found, the shipment would be sent to the CDC if there’s a risk to human health. It would go to the U.S. Department of Agriculture if there’s a risk to livestock, such as heartwater disease, carried by African ticks and devastating to livestock. It’s also possible for an animal to carry a disease without showing symptoms.

To minimize the risk of spreading any disease to other snakes, some reptile importers quarantine their newly imported snakes. At Gourmet Rodents, Layman says, newly arrived ball pythons are immediately treated with an antibiotic and then get weekly veterinary check-ups until they’re sold, so that if they do show signs of an illness, they can get treatment immediately.

Lax oversight, lack of data

Another new paper that’s part of the ball python project, on ball python genetics in Togo, suggests that an important part of what’s supposed to make ranching sustainable—the return to the wild of previously pregnant females and a proportion of juveniles—isn’t being done properly.

It points to the possibility that the animals aren’t being returned to where they were collected, according lead author Mark Auliya, a reptile expert with the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, in Germany. Ball pythons are highly adaptable and can survive in a number of different habitats, but if they’re not released in their native neighborhood, there’s a risk of spreading disease or genetic defects, he says.

Moreover, there are no data on what percentage of released ball pythons survive, which also makes it hard to know whether releases offset collecting. What is known is that some collectors are releasing fewer snakes than they take, according to what they told researchers. Furthermore, half of the those interviewed said they don’t just collect eggs and pregnant females for ranching, but they also look for males, non-pregnant females, and juveniles.

“That is a problem because…previous studies have shown that females are most important in reproduction” for maintaining stable populations, says Christian Toudonou, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Abomey-Calavi, in Benin, where he is studying ball python exploitation and conservation. He says he too has seen indiscriminate collection of males and females, adult and juvenile, in Benin, which, to protect the species, cut its export quota in half in 2017 and has maintained that lower quota in the years since.

It also became clear to researchers that no system is in place to ensure that the ball pythons Togo exports originate from there. Some Togolese hunters told researchers that they often collect ball pythons from across the border in Ghana or Benin, where the species is under “severe threat,” according to a 2015 report by Toudonou. But because those snakes are taken to facilities in Lomé, they get labeled on trade permits as being from Togo. Toudonou and others have documented this practice as well. That undermines the scientific reasoning behind each country’s export quota, D’Cruze says.

He says coordinated export quotas across Togo, Benin, and Ghana would help minimize the impacts of cross-border collecting. Segniagbeto, Togo’s CITES scientific authority who has proposed increased monitoring, also supports a range-wide strategy.

‘An unnecessarily risky business’

The ball python trade “is an unnecessarily risky business from a human health and conservation perspective, and from an animal welfare perspective,” D’Cruze says. “I’m struggling to see how it’s justified.” This collection of ball python studies, he says, is just the start of what we need to understand to make the trade more sustainable, transparent, safe, and humane.

For D’Cruze, the welfare of individual snakes is especially important. He notes that it’s well established in academic studies that reptiles are capable of feeling pain, stress, fear, and anxiety. When it comes to their well-being, we should think of them as we think of dogs and cats, he says. Importers and breeders agree on this point as well, though they often differ on what counts as acceptable conditions.

Much more work must be done to understand the distribution of ball pythons and the status of their populations, Auliya says. When he joined the project, he was shocked at how little ecological information was available. “It’s the most traded live snake species in the world,” he says. “Why did no one ever work on these questions?”

As coordinator for the IUCN’s Red List, an inventory of the global conservation status of species, Auliya says it’s time to consider changing the species’ designation from least concern to near threatened or even vulnerable. “In light of our research and new findings, which point to the issues of improper trade management and regional declines, the Red List status should now be reconsidered also as a precautionary measure,” he says.

Hellebuyck calls ball pythons “a black-and-white situation.” There’s “absolutely no need to import” them, he says, as they’re readily available through captive breeding.

But snake and egg collecting is an important source of income for hunters, Segniagbeto says, so he supports continuation of the trade—with more oversight. Layman, of Gourmet Rodent, says that’s what importers want too. “Our industry is not out there trying to decimate wild populations,” he says. “That doesn’t benefit us. We want to do the right thing and the responsible thing” by supporting sustainable exports.

In the end, it comes down to the buyers, Auliya says. The market for wild ball pythons in North America and Europe exists because people buy them as pets. Buyers need to show responsibility for wildlife, he says. “We as the [customers] are making the most mess. We’re not caring how they harvest them, how they manage them,” he says. “We just want to have them as our pets. We’re exploiting their nature for our purposes.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park