A mecca for rap has emerged in the birthplace of jazz and blues

The edgy rhymes emanating from cities like Baton Rouge spill from a crucible of economic struggle and disenfranchisement.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana — There’s a soundtrack of sorts that can emanate from just about any speaker in a Scotlandville apartment complex. As people move from building to building, while children play on stoops, or as men peer under the car hoods, the bouncing bass flows freely.

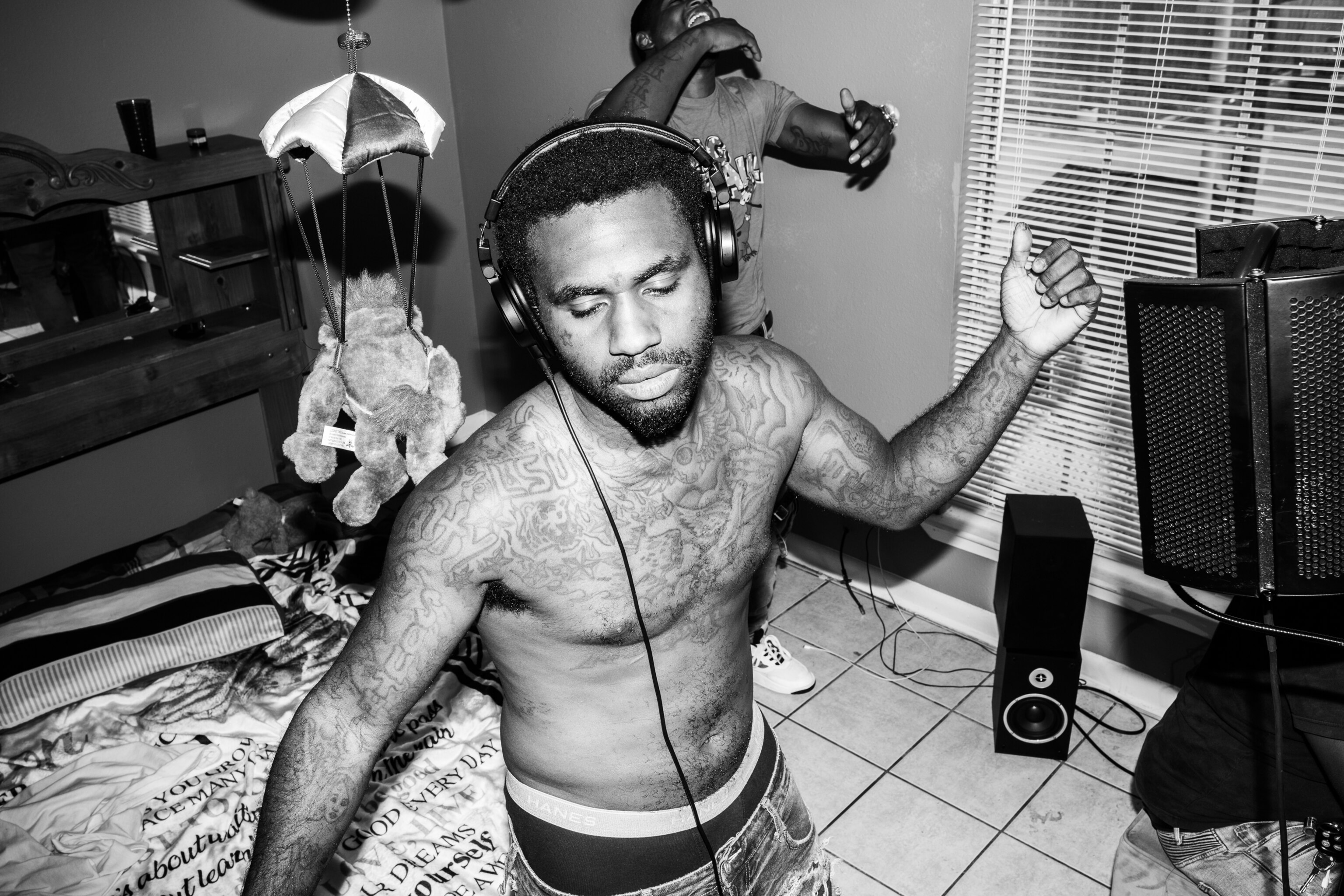

In this Baton Rouge, Louisiana neighborhood—not far from where the state’s first land grant college for African Americans was established—that flow makes heads nod, and teases spontaneous vocals from aspiring rapper La'Jerrian Triplett, aka “Nook Dinero.”

As neighborhood buddies cheer, Nook’s freestyling amps him up. The 21-year-old morphs into a headliner emcee, his arms flailing as he stabs the air with a forefinger. Even a verbal stumble or two in his NSFW (Not Suitable For Work) lyricism didn’t stop him from filling every note as his friends clapped him on.

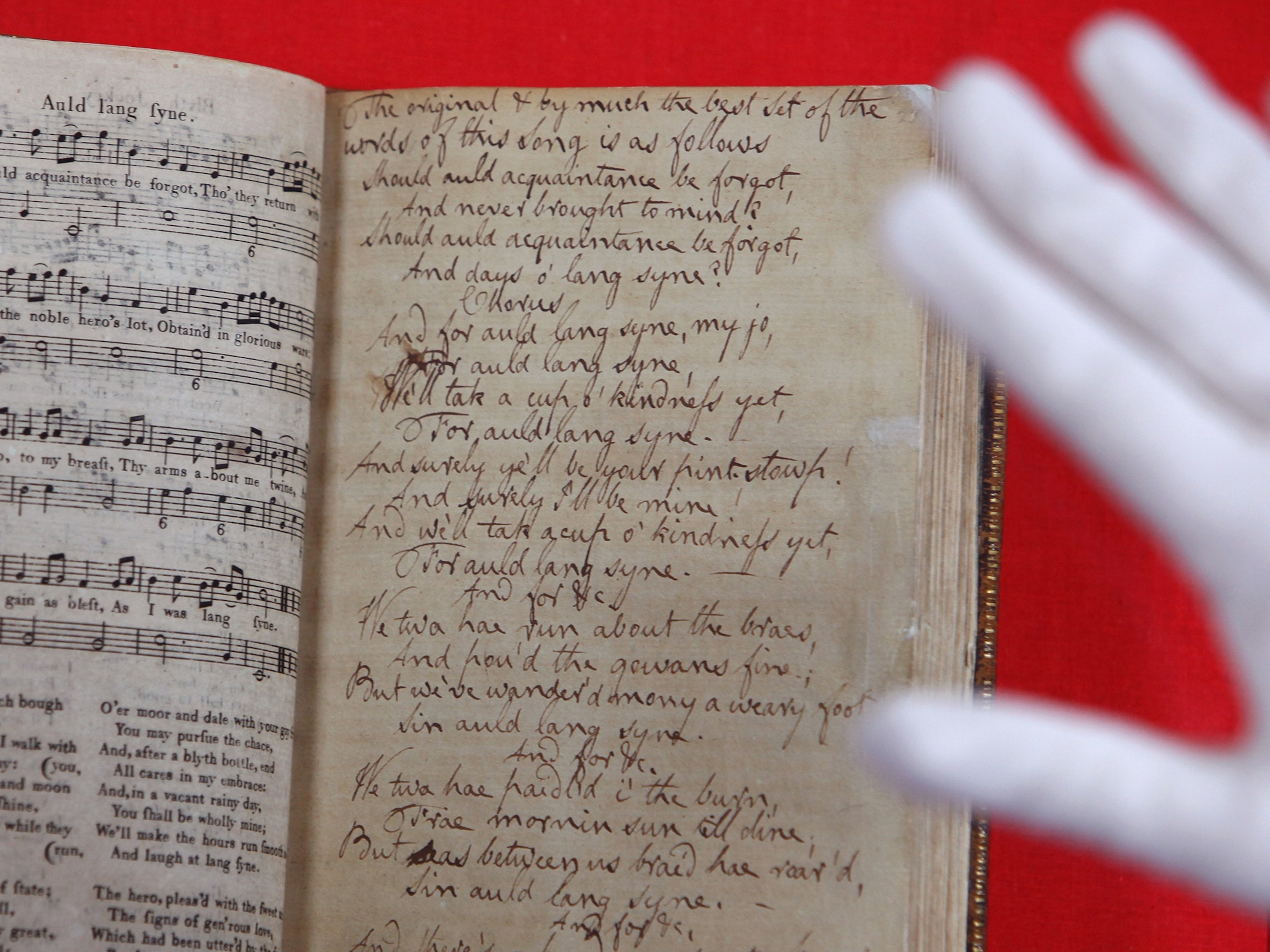

For young Black men like Triplett, the camaraderie and recognition that come from creating rap music gives it a status equal to Louisiana’s other signature musical legacies. For decades, the state’s proud claim to the kinetic riffs of jazz, the swirling rhythm of zydeco, or the frenetic melodies of Mardi Gras Krewes, sealed its reputation as an American musical mecca. But as the influences of rap and hip hop spilled outside their 1970’s New York City birthplace, the versions that emerged from cities like Atlanta, Chicago, New Orleans and Los Angeles forged their own distinctive personas.

Rap is a prominent staple in many Black neighborhoods in Louisiana, as integral as Cajun/Creole cuisine and football dynasties. Possibly the most famous rapper to emerge from the state, New Orleans native Percy Robert Miller Sr., aka “Master P,” conferred the legacy to his son whose first stage name was “Lil’ Romeo.” The family empire has expanded far beyond rapping to include acting, music management and entrepreneurship. Following closely behind Miller is Dwayne Michael Carter, Jr. known worldwide as “Lil Wayne.” The New Orleans native has sold more than 120 million records worldwide and achieved a legendary status of sorts in rap circles.

But like in other regions of the country, the rhymes emanating from cities like New Orleans and Baton Rouge spill from a crucible of economic struggle, incarceration, and disenfranchisement. For example, Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate in the nation, and two thirds of inmates in the state are Black. Many aspiring rappers have been first-hand witnesses to the violence, drugs and criminal activity that result in jail time.

For many youth, rap is a beacon of sorts, wielding the promise for a better life to those whose rhymes are straight fire. For some, it is the only way of life. And you don’t need to play an instrument or take voice lessons to enter the rap game.

“I've been in the trenches too long,” Triplett says. “I ain't going to lie. Like a real-life trench baby. I ain't really never had nothing.”

He’s counting on rap for his come up.

“See, somebody gotta make it and I gotta get it,” he says.

From ‘The Bottom’ to the top in rap

In Baton Rouge, it’s not completely delusional to visualize rap stardom.

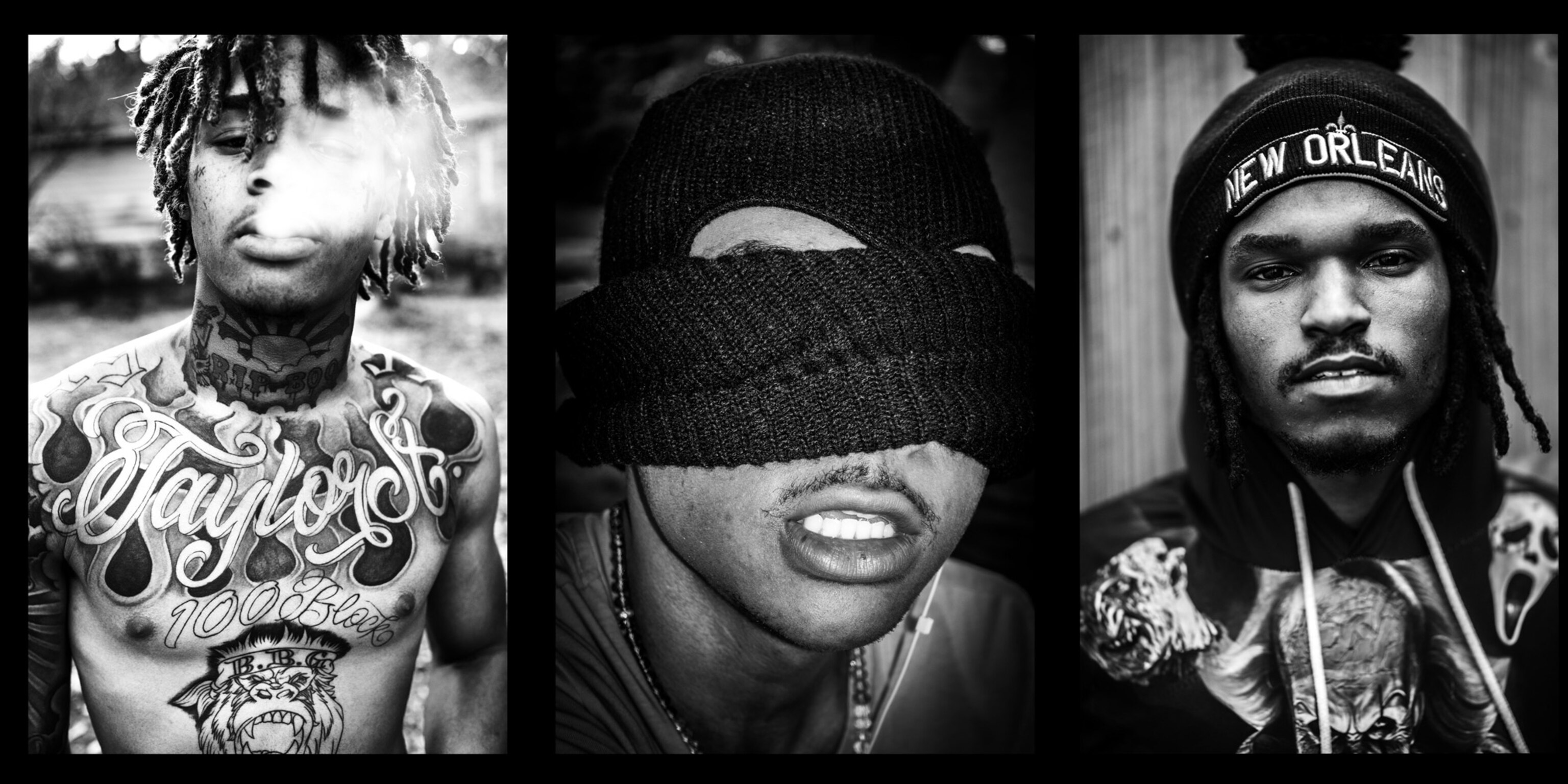

Across the train tracks from Louisiana State University, the largest in the state, is a neighborhood called “The Bottom.” While not the safest area in town, it has produced some of Louisiana’s most successful rap artists, like Torrance Ivy Hatch, better known as “Boosie” or “Boosie BadAzz.” Along with performers like Webster Gradney, Jr, or “Webbie,” rappers with a Baton Rouge imprint have inspired young men and women across the state for the past few decades.

The sound that aspiring artists from Baton Rouge claim as their own is known as “bounce” or “dirty south flow.” There’s a distinctive vibe to each rapper's voice, which they believe gives them authenticity. Though bounce music is mostly upbeat and aimed at getting people on the dance floor, other forms are more mellow and tell more intimate stories through the music.

“Young Boy Never Broke Again” (aka “NBA Youngboy”), or Kentrell Gaulden is also from Baton Rouge. He’s one of the most popular rappers in the nation at the moment, having charted 20 albums on the Billboard 200 since 2017. Though Gaulden’s career is interspersed with numerous criminal charges, his fan base in Baton Rouge continues to support him.

But the aura of possibility around rap music isn’t just for Generation Z.

Wildside Yella is 49 years old and once was an aspiring rapper himself. He was born and raised in “The Bottom” and used to work with the older generation of Baton Rouge rappers like Glenn Clifton, Jr. aka “Young Bleed” and Boosie. Now he manages an emerging crew, which is part of his Wildside Entertainment label. His main act is called BBG, aka Bottom Boy Gorillas, some of whom have collaborated with NBA Youngboy and other popular artists.

Though his own shot at superstardom has passed, Yella believes using his experience to nurture rap skill is his way of keeping youth off the streets and out of prison.

“In every ghetto, everybody got a story to tell. Down here, we’re just telling our side of the story and that's where the passion comes from.” Yella says. “Cause that's what I was trying to do. If I can help one of them out and put a mic in their hand and take the guns off, I’ll do that.”

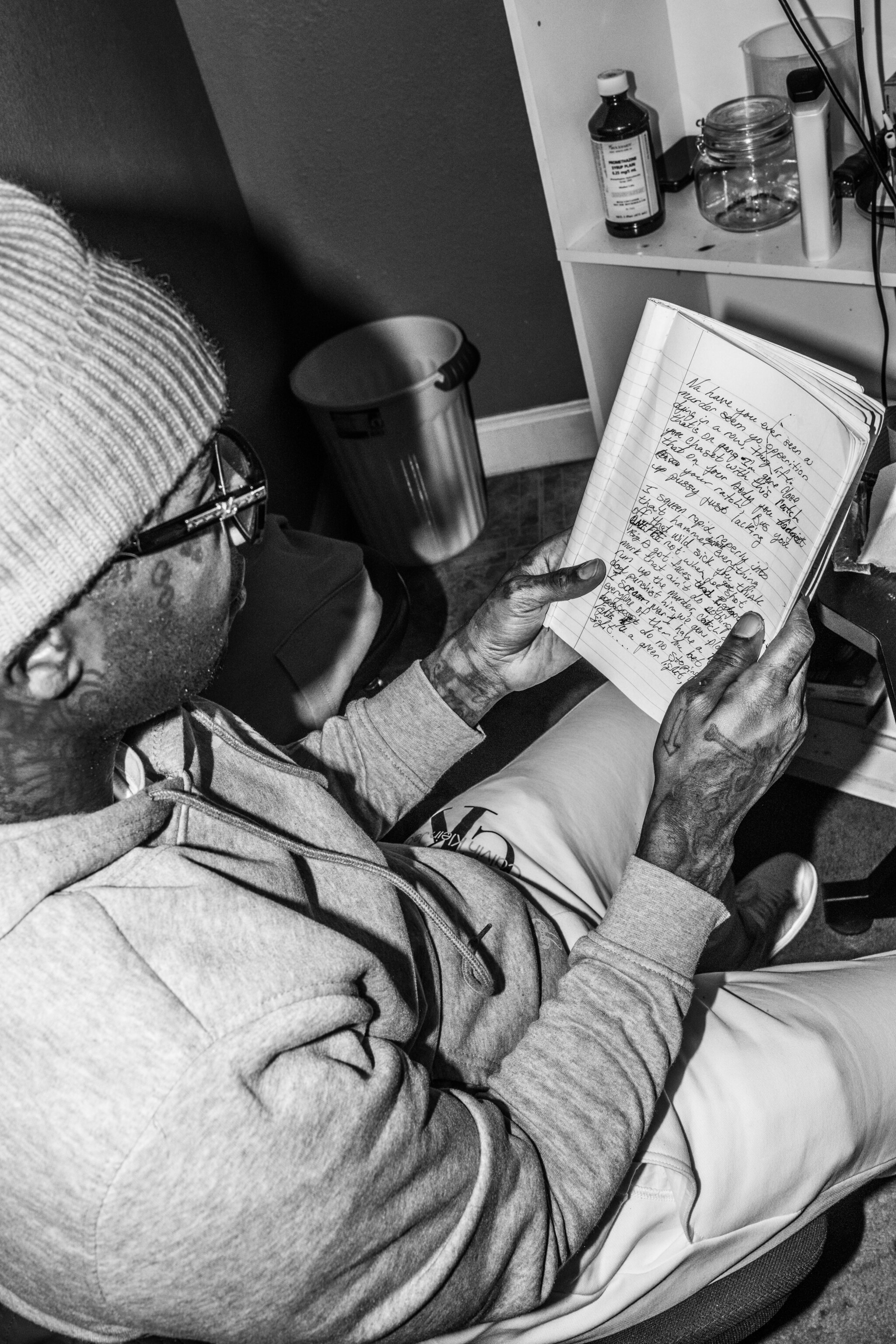

One person who understands the consequences of incarceration is 42-year-old Keon Wilson, aka “One Feezy.” He was released from prison in July of 2020 and has already begun to work on some new musical projects. Before his 2008 arrest on charges he preferred not to discuss, Wilson was a rapper, engineer, and producer. His love for music has spanned his whole life, including a stint in his high school band. He believes that too often, the musical passion artists like him feel is discounted and dismissed.

“I'm not gonna rap for you to bob your head to my music for you just to feel my melody. Yeah, I ain't finna rap like that.” Wilson says. “I’m going to rap where your soul is going to be bobbing its head. Your soul bobbing it from the inside and before you know it you’ll say, ‘Hold on, play that back man.’ ”

Wilson has passed down that same love for music to his son who is also a member of Bottom Boy Gorillas. But Wilson knows he can’t push him to stardom.

Emerging Women Rap Artists

The lavish lifestyle of bling and fancy cars that many artists boast about in their music is far from the norm in Louisiana. But even the outrageous odds against success don’t dampen the appeal for many young artists. And though rap music can’t shake complaints that its violence and misogyny have degraded the Black community, it’s equally popular with women and girls.

While the majority of aspiring Louisiana rappers are male, women like 25-year-old Deshay Carter, aka “Female Rapper” are emerging on the scene. She has gained a substantial social media following and recognition for her music, with nearly 20,000 followers on Instagram. Carter wants to be the first woman rap superstar from Baton Rouge, and she’s already on track to do so. But she’s determined to be authentic, unlike some of her peers whom she says are merely copy-catting others.

“They are trying to be like Miami and Atlanta, and they are trying to be like other females and don't want to rap about what we go through down here,” Carter says. “Like they're ashamed of this life, coming up like this, I guess. And they want to rap about Popping P and getting people out of money and stuff like that.”

Carter had her first child at 13 and now has two daughters, age 12 and 11. She’s counting on her rap skills to create a secure future, which means controlling the rights to her work. And like every other rapper just about everywhere else in the world, Carter uses the creative process as fuel.

“The motivation to keep going with it is my kids and my mom, and I know where I'm trying to get us,” Carter says. “And not only that, it's just the motivation, just to know somebody out there looking up to you rapping your music."

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

Travel

- A guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadowA guide to Philadelphia, the US city stepping out of NYC's shadow

- How to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplingsHow to make perfect pierogi, Poland's famous dumplings

- The best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard ofThe best long-distance Alpine hike you've never heard of

- Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard