Japan had little chance of victory—so why did it attack Pearl Harbor?

Long-simmering tensions with the U.S. over expansion in Asia came to a head on December 7, 1941.

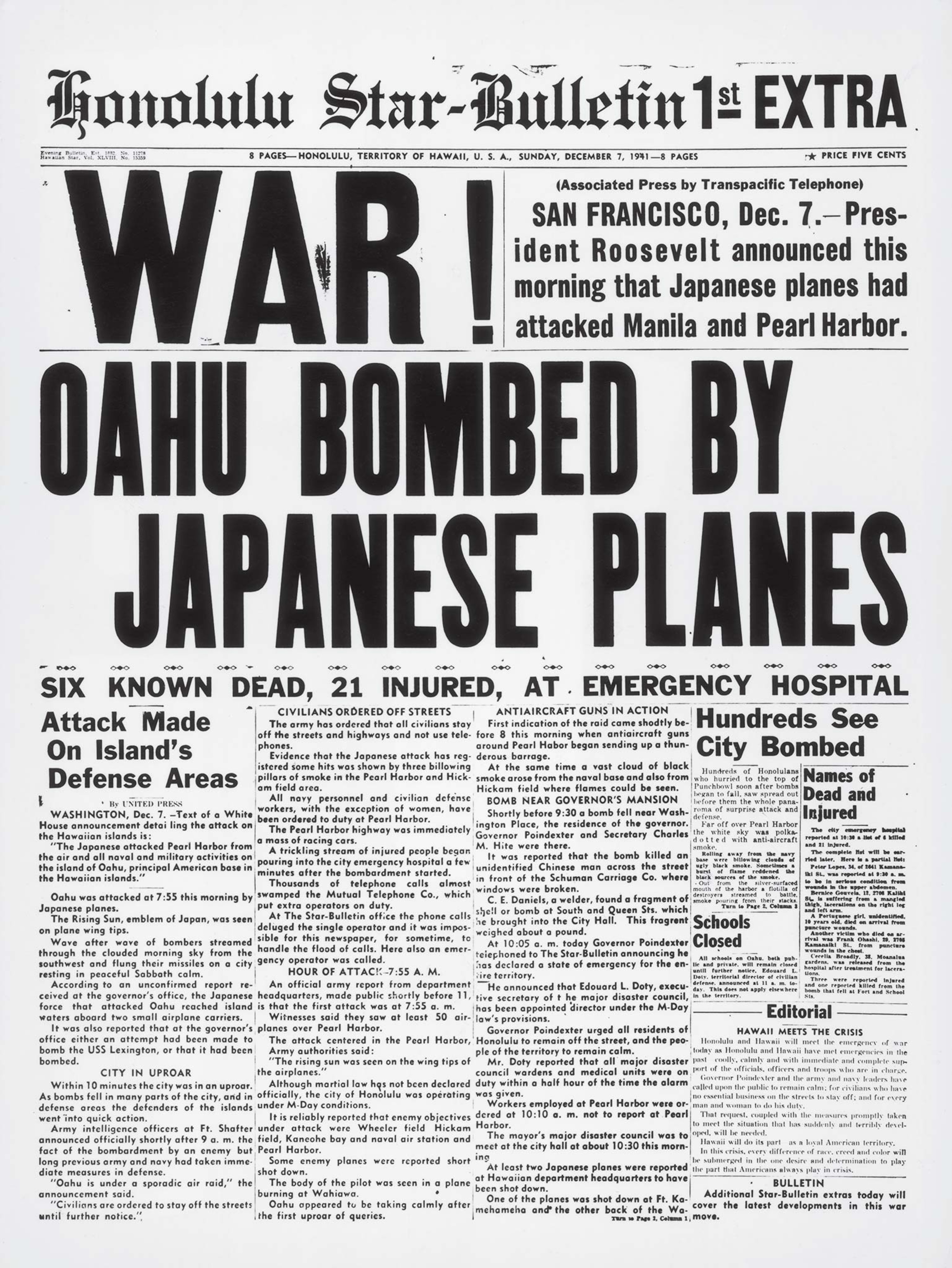

“Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is no drill.” When that urgent message from Honolulu reached Washington, D.C., on December 7, 1941, even those who anticipated conflict with Japan were stunned by the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, nearly 4,000 miles from Tokyo. “My God, this can’t be true!” said Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox.

Japan’s leaders had hatched a daring plan to let the United States know who was in control of the Pacific. The surprise attack had been in the works for months before the first bombs fell.

(80 years after Pearl Harbor, here's how the attack changed history.)

Simmering tensions

Japan had begun an imperial expansion in the late 19th century, seeking out natural resources for the island nation as well as buffer states to protect it. It defeated China in the 1890s to gain control of Korea and triumphed over Russia in the 1900s to seize the Liaodong Peninsula and parts of Manchuria for itself.

In the early 20th century, Japan’s imperial efforts continued unabated as it took more and more territory from China, but by the mid-1930s relations between Japan and the United States had become strained. Through diplomacy and sanctions, the U.S. was trying to prevent Japan from becoming a great imperial power—a stance that seemed somewhat hypocritical. Why, Japan’s leaders asked, should their nation abandon expansion at the insistence of Americans who had colonized Hawaii and occupied the Philippines? If the price for peace was to grovel and pull back, then they would fight.

(See maps of nine key moments that defined WWII.)

First strike

Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II, had lived in the United States when studying at Harvard University and during later tours of duty in the 1920s. Yamamoto understood that provoking the United States with a direct attack could have deadly consequences for he had seen the nation’s vast natural resources and industrial capacity. He warned that to “fight the United States is like fighting the whole world.”

The only hope, Yamamoto surmised, was to smash the Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor before the U.S. Navy had a chance to fully mobilize. If Japan did not rout the Pacific Fleet and prevent Americans from bringing their strength to bear, Japan would be in a world of trouble. Only a quick, powerful, pre-emptive strike could hobble the U.S. in the Pacific.

Japan authorized war preparations on July 2, 1941. Planning for the attack on Pearl Harbor began.

(The women codebreakers of World War II helped end the war.)

No turning back

On November 26, 1941, Yamamoto launched six big aircraft carriers with more than 400 warplanes of the First Air Fleet on their decks, escorted by battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines. To avoid detection, the force followed a little-traveled, northerly route to Hawaii. Before daybreak on December 7, the Japanese carriers reached the assigned position a few hundred miles north of Honolulu.

(The Nisei soldiers who fought WWII enemies abroad—and were seen as enemies back home.)

War rituals

Up before daybreak on December 7, Japanese naval aviators aboard the aircraft carriers commanded by Vice Adm. Nagumo sat down to a ceremonial breakfast of rice and red beans and took sips of sake before setting out to attack the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. They did not have to wait until they achieved victory to honor their mission. These men believed that one who entered battle for his country and its exalted emperor was blessed, whether he prevailed or perished. Cmdr. Mitsuo Fuchida, chosen to lead the attack, spoke for many when he recalled his feelings that morning. “Who could be luckier than I?” he asked. In risking his life for what he cherished, he wrote, “I fulfilled my duty as a warrior.”

The rising sun

As dawn glimmered around 6 a.m., the carriers turned into the wind to launch the first wave of 183 fighters, bombers, and torpedo planes, even as heavy seas made conditions hazardous. “The carriers were rolling considerably, pitching and yawing,” recalled a pilot who was waiting to take off with the second wave of attackers an hour later.

When planes left the flight deck, they sank out of sight before bobbing up above the clouds. Fuchida, who worried that cloud cover would obscure their target, was reassured when his radio picked up Honolulu’s weather forecast, promising clear skies. Residents there, waking to what looked like another placid Sunday in paradise, had less than two hours of peace left.

(How the advent of nuclear weapons changed the course of history.)

Missed warnings

At 6:45 a.m., Lt. William Outerbridge, captain of the destroyer U.S.S. Ward, dropped depth charges on a small submarine lurking near the narrow entrance to Pearl Harbor. Operated by a two-man crew and armed with a single torpedo, the midget Japanese sub was among five assigned to go where the larger submarines that hauled and released them could not safely enter, by slipping furtively into the shallow harbor and targeting American warships. Although Outerbridge reported the startling incident, communications were slow on Sunday morning. It took an hour for his report to work its way up the chain of command to Kimmel, by which time Fuchida and his men had Pearl Harbor in sight.

The second warning came around 7:15 a.m. when Pvt. Joseph Lockard, operating a mobile radar station near Kahuku Point at the northern end of Oahu, detected an “unusually large flight” of aircraft approaching at a distance of less than 100 miles. “Don’t worry about it,” replied the watch officer of the U.S. Army Air Force 78th Pursuit Squadron. He assumed the planes were friendly B-17 bombers, expected in from California for a stopover at Pearl Harbor before they continued on to the Philippines. No fighters were dispatched, and no word of Lockard’s report reached General Short before the attack began.

This is no drill!

At 8 a.m. sharp, as a band on the deck of the U.S.S. Nevada began playing the national anthem for the raising of their flag, a squadron of 40 Japanese torpedo planes bore down on the harbor. One hit the battleship U.S.S. Oklahoma, docked near the Nevada, whose band members scrambled for cover. Within moments, a torpedo struck the Nevada explosively.

The damage done by torpedoes was compounded by bombs dropped at high levels that crashed through the decks of warships before detonating. Around 8:20 a.m., a bomb penetrated the forward magazine of the battleship U.S.S. Arizona where gunpowder was stored, triggering a volcanic blast that killed hundreds of men instantaneously. Of the nearly 1,400 men aboard the Arizona that morning, fewer than 300 survived.

Bloody Sunday

Around 9 a.m., the second wave of warplanes swooped in and wreaked further havoc. By the time the last attackers departed around 9:45 a.m., all eight battleships and 11 other warships had gone down or been severely damaged. Most eventually would be repaired, but the Arizona and Oklahoma were ruined and those on board accounted for nearly three-fourths of the Navy’s casualties on this bloody Sunday.

Losses among members of other services and civilians brought the toll to more than 2,400 killed and nearly 1,200 wounded.

(Pearl Harbor survivors forgive—but can't forget.)

Waking the sleeping enemy

When Fuchida and his airmen returned to their carriers, the elation they felt at catching their foes off-guard drained away. For all the harm done at Pearl Harbor, the Pacific Fleet had not been incapacitated. The oil depots and repair yards on which it depended had suffered little damage.

Admiral Yamamoto, who later learned of the results, stated there was no glory in mauling a “sleeping enemy” who was now wide awake and capable of striking back. He knew the tide might turn against him if he did not complete the task his fleet left unfinished on December 7.

(The U.S. forced them into internment camps. Here’s how Japanese Americans started over.)

‘A date which will live in infamy’

Within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese forces struck several other targets up to 6,000 miles away to clear the way for invasions that would follow. It was the broadest offensive ever launched at one time by a single nation. Japanese troops advanced on the British stronghold of Singapore. Among the American targets bombed on that same day were bases on Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, where dozens of fighters and B-17 bombers were destroyed on runways at Clark Field. As President Roosevelt stated when asking Congress to declare war on Japan, this day would “live in infamy.”

The Japanese show of force hurt the United States, and it would be many desparate days before American and Allied forces could begin to reclaim lost ground in the Pacific theater.

(In WWII, the Japanese invaded Guam. Now they’re welcomed as tourists.)

To learn more, check out Pearl Harbor and the War in the Pacific. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.