A brief history of matzoh: 'It's not supposed to taste good'

Restrictions around matzoh are meaningful and refreshing to many: here’s why.

Matzoh, known by Jews worldwide as “the bread of affliction,” is a cracker-like food made of flour and water eaten to commemorate the Hebrew slaves’ exodus from Egypt. The bland crisp takes the place of bread for the eight days of Passover.

While the aforementioned affliction may have changed over the years from one of desert-trekking deprivation to palatal hardship, most Hebrew scholars agree on one thing: It is not supposed to taste good.

Yet, for at least the first day of the holiday, many people actually crave it. Why?

For answers to this burning question about the nature of matzoh, we turn to Michael Wex, the author of Rhapsody in Schmaltz: Yiddish Food and Why We Can’t Stop Eating It.

“Now we eat it because we don’t have to eat it,” he says. In other words, because God’s chosen people have other choices the rest of the year, they look forward to eating matzoh to commemorate when Jews had no other choice but matzoh. And when it pops up in the grocery stores, many non-Jews pick up a few boxes, too.

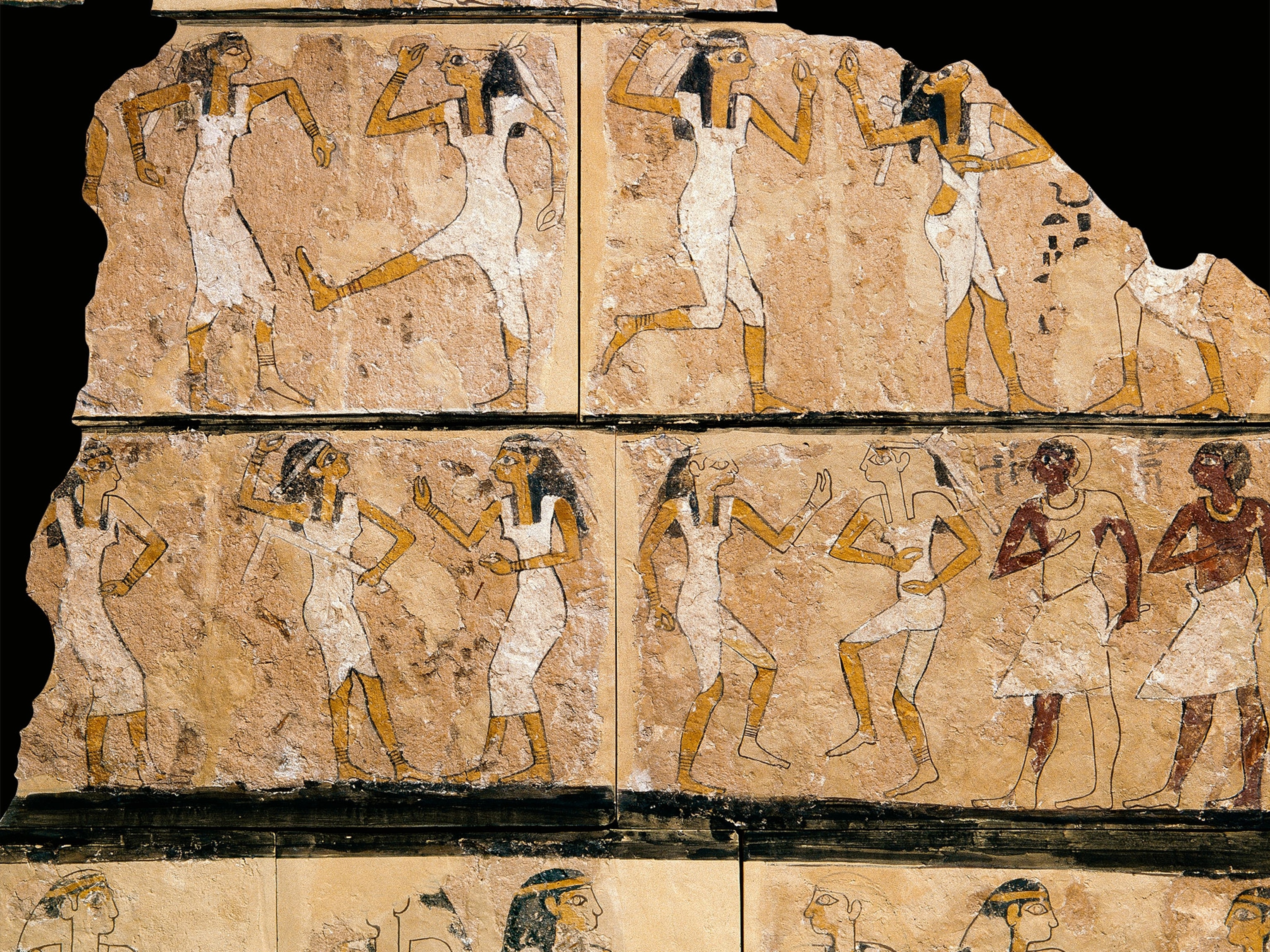

According to the Hebrew bible, after a long protracted battle that featured God-directed plagues like frogs, boils, locusts, and the slaughter of first-born sons, the Egyptians freed the Hebrew slaves. The Jews left hastily, without time to let their bread rise. God basically tells them to take their dough and go, and that they’ll be cut off from Him if they eat anything leavened, i.e. yeasted or risen, for seven days. Hence—the first matzoh—the “roadside fast food from the ancient near East,” as Wex calls it.

The Passover seder dinner is centered around the matzoh, and is a virtual reenactment of the story of Exodus. In our family, the long, ritualistic dinner is frequently summed up for uninitiated guests in this way: “They tried to kill us, we’re still here, let’s eat.”

And so we eat matzoh, both plain and in forms that attempt to make it more palatable by adding salt and egg to create dumpling-like matzoh balls for chicken soup; or by topping it with sugary jam. Kids particularly love chocolate-covered matzoh for dessert.

Yes, there are other foods served at Passover, much of which varies according to where you’re from or what your grandma always made. Ours almost always includes brisket, kugel (a kind of casserole), and some kind of token vegetable. But matzoh is front and center.

There are strict specifications for making matzoh, of course. (Judaism is all about rules.) First of all, you only have 18 minutes from adding water to the flour to bake it. That’s the amount of time scholars say you have before the dough starts to rise, which would make the whole business un-kosher for Passover.

The result is a thin, flat plate-sized wafer “without even a kiss of salt,” Wex says. The first matzoh were probably round. The advent of machine-made matzoh led to the rise of the easier to pack and stack square marvel many of us know today. But the flavor? Pretty much the same, to my taste.

There are also prescriptions for the matzoh to be harvested at a certain time of day and when it is dry enough, as prescribed by a rabbi, to prevent fermentation (i.e. leavening.) Dan Barber, back-to-the-land advocate and chef, made the case that the result of this close supervision may mean the wheat harvested is of higher quality, and therefore Jewish law may actually make food taste better.

But Wex and other scholars say this is beside the point. From Rhapsody in Schmaltz:

“There are those who say that God gave us cardboard so that we could describe the taste of matzoh, but taste is what matzoh is not about...Matzoh doesn’t need to be good, it only needs to be there—inside of 18 minutes. Or 22, according to some authorities; however long it took to walk to Tiberias from Migdal Nunia, the probable home of Mary Magdalene—a single Roman mile.”

Wex argues that the creation of Jewish dietary laws, particularly as they relate to matzoh, create for Jews a sense of otherness. While rules like no pork and no cheeseburgers may seem oppressive these days, in ancient times, it gave the Jewish people a new way of thinking. Once they were no longer slaves, they were “free to act in ways that have nothing to do with Egypt,” including, throwing out all their learned notions of what to eat.

There are entire Jewish communities, of course, who follow the ancient prescriptions to the letter for Passover and beyond. But do modern Jews still need to follow these ancient laws? Wex says you can have a strong Jewish conscience and not follow the dietary laws, but you should understand them “if you want your religion to stick around.”