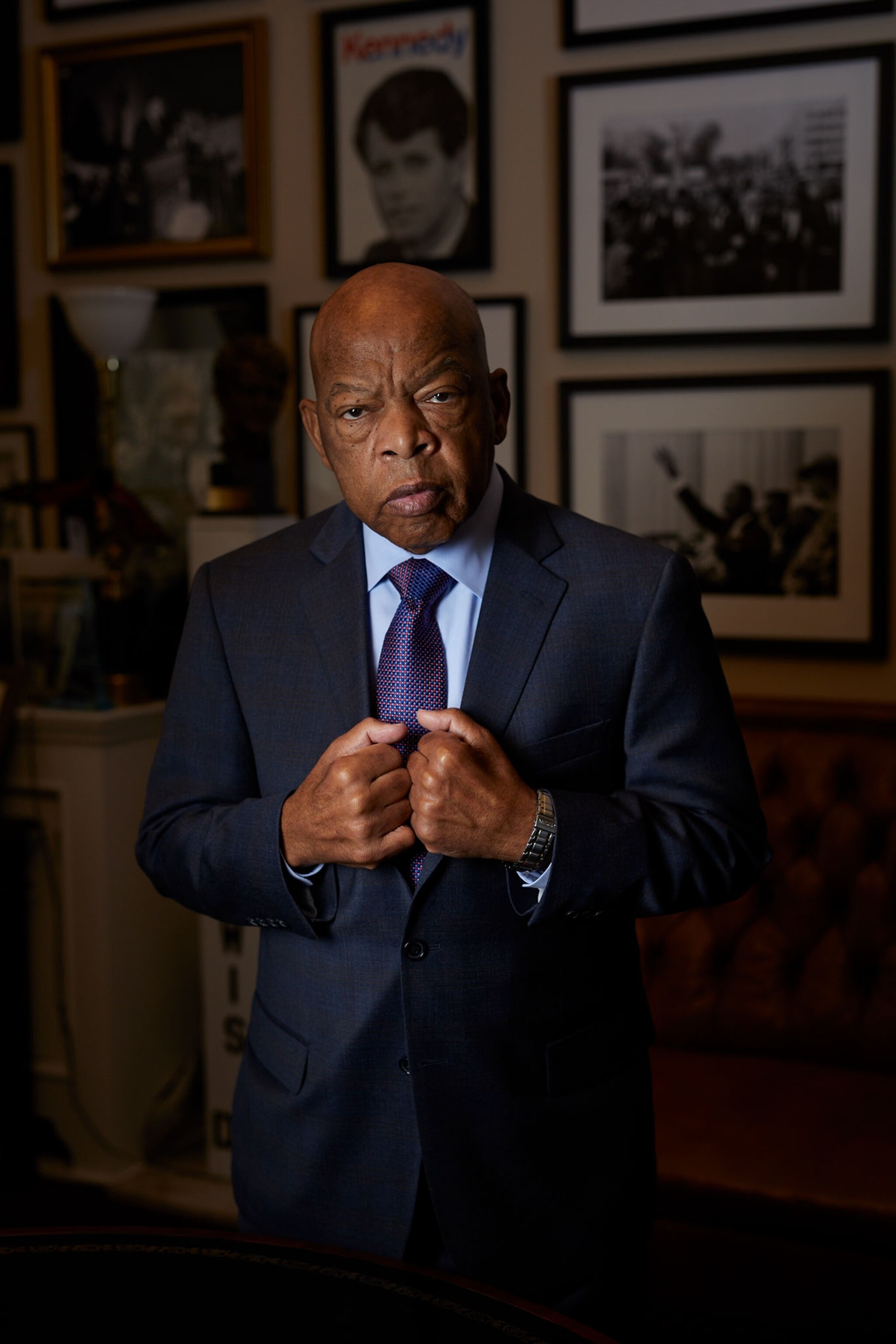

How John Lewis spent his life bridging America’s racial and political divides

The pioneering civil rights leader was a champion of non-violent protest and change, despite the violence he himself suffered.

Upon learning of the death of Nelson Mandela in 2013, John Lewis offered a moving tribute to South Africa’s first Black president. His written homage offered compelling insight into the minds of both of the storied civil rights leaders.

“The first time I had a chance to meet him was in South Africa after his release from prison. He gave me this unbelievable hug. I will never forget it,” Lewis recalled in a statement released by his congressional office. “He said, ‘John Lewis, I know all about you. You inspired us.’ I said, ‘No, Mr. Mandela, you inspired us.’ I felt unworthy really to be standing at his side. I knew I was in the presence of greatness.”

Few contemporary Americans were better qualified than John Lewis to speak on greatness or reflect on the virtues of leadership and bravery. Before pancreatic cancer claimed him last week at the age of 80, Lewis was the living embodiment of those qualities. Tributes in his honor now abound, while flags fly at half-staff. Lewis is being widely remembered as a towering figure in America’s civil rights movement and the conscience of the United States Congress. However, there’s more to his considerable legacy. Lewis was also a bridge—a human bridge—that history will judge reverently.

The life of Lewis spans America’s violently segregated past, as well as the racially combustible moment we currently occupy. Born the son of Alabama sharecroppers, he was hand-selected by the Congress of Racial Equality to become one of the original 13 Freedom Riders. The riders were an integrated group of young people who rode interstate buses with the intention of directly confronting segregation in public transportation. The practice of segregated seating on buses had been outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1956, but the ban was rarely enforced in the South.

As a result of his activism on bus lines and through his work with the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Lewis became the target of frequent physical attacks. He paid a horrendous price in blood and numerous incarcerations for his non-violent advocacy seeking the integration of water fountains, diners, and other staples of daily living. Some of his committed colleagues paid with their lives. Somehow, Lewis survived. He eventually became a justice sentinel recognized by many, including the likes of Mandela.

As his life’s end approached, Lewis remained active and vocal in the pursuit of racial justice. Although his body weakened, he continued to closely examine the nation’s landscape and forcefully speak out against injustice. He recognized that his life’s work must continue, and he seemed to take comfort in the growing coalitions of young Americans committed to challenging systemic racial unfairness. He could clearly see that the bridge his life represented was being navigated by the next generation.

The horror of watching the death of George Floyd on a Minneapolis street this past May transported Lewis back to childhood and the adolescent years before his life became synonymous with a dogged pursuit of social justice. The 1955 lynching of Emmett Till in the Mississippi Delta was also on Lewis’s mind.

“I was 15 years old—just a year older than him. Despite real progress, I can’t help but think of young Emmett today as I watch video after video after video of unarmed Black Americans being killed and falsely accused. My heart breaks,” said Lewis days after Floyd’s death.

But then—just as he had done all of his life—John Lewis provided leadership. Speaking to those actively engaged in the continuing quest for justice, as well as to future leaders in formation, Lewis said:

“My fellow Americans, this is a special moment in our history. Just as people of all faiths and no faiths, and all backgrounds, creeds, and colors banded together decades ago to fight for equality and justice in a peaceful, orderly, non-violent fashion, we must do so again. Rioting, looting, and burning is not the way. Organize. Demonstrate. Sit-in. Stand-up. Vote. Be constructive, not destructive. History has proved time and again that non-violent, peaceful protest is the way to achieve the justice and equality that we all deserve.”

Given the social and racial unrest currently roiling America, the wisdom and patriotism of Lewis has never rung truer. It’s easy or convenient to forget that Lewis—trained in the ways of non-violent confrontation so effectively used by Mahatma Gandhi and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.—wasn’t always a disciple of carefully nuanced language. However, he always understood the importance of youth—even intemperate youthful energy—in the civil rights arena. Perhaps that’s why he championed the activism of Black Lives Matter, and appeared to view the group as a viable successor to the justice movement.

In early June, well into the final stage of his battle with cancer, Lewis donned a mask and paid a visit to the newly named Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C., near the White House. He toured the plaza with D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and praised the mayor’s embrace of BLM’s call for sustained protest. As he viewed the words Black Lives Matter emblazoned on the street in large yellow letters, he was moved. He described the insignia as a “powerful work of art.” He was confirming yet again his long-held convictions of the power of the young to foment change. (Hear from those calling for racial justice in Washington.)

When he spoke at the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963—where King delivered his famous “I Have A Dream Speech”—Lewis, then only 23, had initially planned to address the crowd using language that the march organizers considered inflammatory.

The original ending of Lewis’s speech read: “The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently.” (Here's how Jim Crow laws created "slavery by another name.")

Lewis’s elders in the movement, and the key organizers of the march—including A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and King—insisted that the SNCC leader temper his rhetoric a bit. There were bridges to be built and fragile cross-racial alliances to strengthen in America, where legalized racism remained entrenched. Lewis resisted mightily at first, but he ultimately relented. The crowd of 250,000 people heard the young activist end his speech with these words: “But we will march with the spirit of love and with the spirit of dignity that we have shown here today.”

A major turning point in the civil rights movement involving Lewis occurred on March 7, 1965. The day is commonly referred to as Bloody Sunday. Lewis and nearly 600 people gathered at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, and attempted to march across the bridge, named for a Confederate general and reputed grand dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. The protestors were demanding the elimination of literacy tests and other practices used to deny Blacks the right to vote.

The peaceful demonstration descended into bloody chaos when troopers on horseback wielding bullwhips, rubber tubing wrapped in barbed wire, and deploying tear gas charged at the marchers. No deaths resulted that day, but numerous marchers suffered broken bones. Footage televised on national news showed Lewis being cracked in the skull and knocked to the ground by an Alabama state trooper, who struck him a second time as he attempted to rise.

The national outrage was instant and galvanized political support. Less than ten days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law, a measure that banned the use of literacy tests and poll taxes that were widely used to prevent blacks from voting in many state and local elections in the South.

Weeks before Lewis died, an online petition was created to rename the Alabama bridge where Bloody Sunday occurred. The renaming effort has drawn considerable social media support, along with the strong endorsement of Lewis’s longtime friend and House of Representative colleague James Clyburn of South Carolina.

However, Lewis may have taken issue with the bridge being offered as a tribute to his legacy. In an AL.com newspaper commentary he co-authored with U.S. Representative Terri Sewell in 2015, Lewis spoke against the possible renaming of the Edmund Pettus bridge:

“Renaming the bridge will never erase its history. Instead of hiding our history behind a new name we must embrace it—the good and the bad. The historical context of the Edmund Pettus Bridge makes the events of 1965 even more profound. The irony is that a bridge named after a man who inflamed racial hatred is now known worldwide as a symbol of equality and justice. It is biblical—what was meant for evil, God used for good.”

Now, in the wake of Lewis’s death, many Democratic legislators have renewed their effort to gain passage of the Voting Rights Advancement Act, passed by the House in 2019. The legislation, which stalled in the Senate, would restore key protections of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that the Supreme Court struck down in 2013. Among other things, the legislation seeks to eliminate partisan systems of gerrymandering, limit efforts to purge voting rolls, and ensure the voting rights of felons no longer incarcerated.

A growing chorus of people now suggest renaming the 2019 voting rights bill after Lewis, who voted for and strongly endorsed the legislation. It would be a fitting tribute. Lewis understood the sanctity of the ballot and spent his life in pursuit of justice and a more perfect union.

“The vote is precious,” Lewis said in June as the U.S. House considered the voting rights legislation, which eventually passed the chamber along strict partisan lines. “It is almost sacred. It is the most powerful non-violent tool we have in a democracy.”

One day soon, John Lewis may have a bridge posthumously named in his honor. It would be well deserved. In the meantime, we benefit by continuing to learn from the life’s work of a civil right giant who himself became a bridge connecting the past to the future. Lewis not only inspired Mandela. He inspired generations of leaders, and undoubtedly will inspire more still to come.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

- Why young scientists want you to care about 'scary' speciesWhy young scientists want you to care about 'scary' species

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- Behind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festivalBehind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festival

Environment

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

History & Culture

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

Science

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

- Why dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a rewardWhy dopamine drives you to do hard things—even without a reward

- What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?What will astronauts use to drive across the Moon?

- Oral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuriesOral contraceptives may help lower the risk of sports injuries

- How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out.

- Science

How stressed are you? Answer these 10 questions to find out. - Does meditation actually work? Here’s what the science says.Does meditation actually work? Here’s what the science says.

Travel

- How to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake ComoHow to explore the highlights of Italy's dazzling Lake Como

- Going on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboardGoing on a cruise? Here’s how to stay healthy onboard

- What to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destinationWhat to see and do in Werfen, Austria's iconic destination

- How to get front-row seats to an active volcano in GuatemalaHow to get front-row seats to an active volcano in Guatemala