COVID rebounds aren't definitively linked to Paxlovid—here's what we know

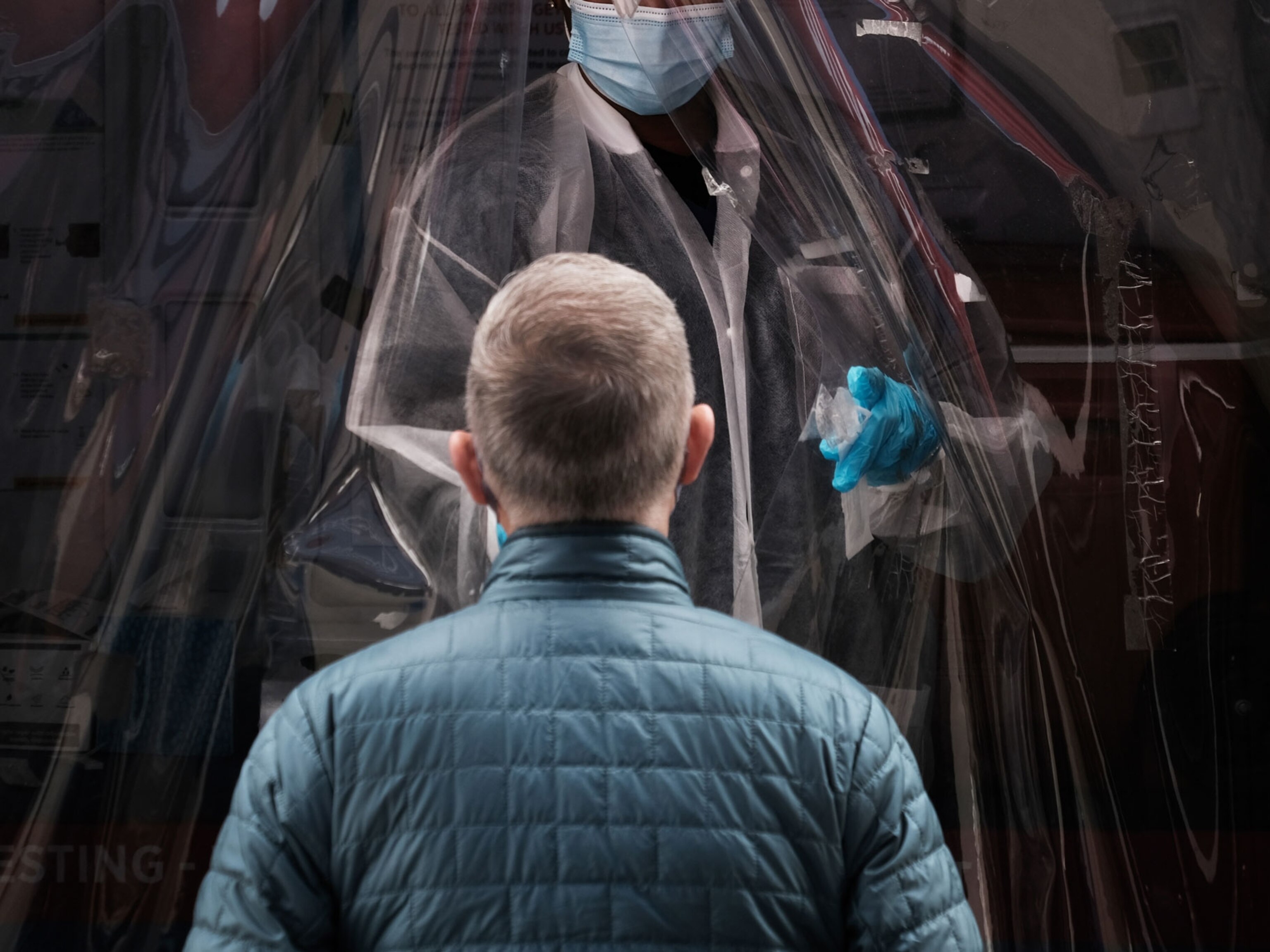

Rising numbers of people are getting sick again within days of testing negative. But the reasons why are murky, including unclear links to antiviral drugs.

When Anthony Fauci announced in June that he had experienced a “rebound” case of COVID-19—testing positive mere days after a negative test result—many Americans were shocked this could happen. But in the intervening weeks, a growing number of people have suffered a rebound themselves or encountered others in similar straights, including another high-profile case just last week of President Joe Biden.

“It’s hard to ignore the anecdotal evidence of rebounding peppered throughout social and mass media,” says Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health who writes the popular blog Your Local Epidemiologist.

A rebound occurs when a person tests positive for COVID-19 or suffers a recurrence of symptoms between two and eight days after recovering from the initial infection and testing negative, according to a health alert for physicians issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in May. In many cases, the rebound is happening in people taking an antiviral medication, which is recommended for individuals at high risk of progressing to a severe form of COVID-19, ending up in the hospital or dying from the infection.

Those are the known facts. Everything else about rebound is currently subject to speculation.

“There’s a lot we don’t know right now,” Jetelina says. “We don’t know how often this is happening, and we don’t know what’s causing it.” And while the phenomenon is often linked to antivirals, more than one factor may be involved.

How frequently are COVID-19 patients rebounding?

Pfizer’s official clinical trial for its antiviral Paxlovid took place when the Delta variant was predominant in the U.S. That trial reported that fewer than 2 percent of people taking the medication—which involves two pills taken twice daily for five days—experienced rebound.

But doctors who have prescribed Paxlovid in more recent months say that figure is likely now a woeful undercount.

Scott Roberts, an infectious diseases physician at Yale Medicine, says his experience puts the number closer to 5 percent. That tracks with a study posted online but not yet peer-reviewed in which researchers from Case Western Reserve University evaluated rebound cases following courses of Paxlovid and Lagevrio—the Merck antiviral generically known as molnupiravir—between January and June 2022.

Paxlovid is the more widely prescribed antiviral, with three million courses given since its emergency authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last December. By contrast fewer than half a million courses have been administered for Lagevrio.

In the Case Western Reserve research, some 3.5 percent of Paxlovid takers rebounded after seven days; for those taking Lagevrio, the number was close to 6 percent.

With the latest Omicron variant, BA.5, dominant in the U.S. since early July, some doctors think today’s rebound numbers are not only higher but will continue to rise. Aftab Khan, an internal medicine physician in Davenport, Florida, says that about a quarter of his elderly Paxlovid patients have rebounded, and he expects a further increase because this wily subvariant is likely even better at evading antibodies.

Is rebound linked to antiviral treatment?

Though the rate of rebounds seems to be higher in those taking antiviral medicine, there isn’t enough data to definitively say that there is a link between the two.

In the Pfizer Paxlovid trial, patients taking placebos rebounded at rates similar to those getting the drug. The CDC states that a brief return of symptoms “may be part of the natural history” of COVID-19 in some people, whether or not they’ve received an antiviral. For this reason, the CDC calls the phenomenon COVID-19 rebound rather than the more widely used term Paxlovid rebound.

But Yale’s Roberts says that while symptoms did reappear in some cases before the antivirals were authorized, this was very rare.

What causes COVID-19 to rebound is another issue that’s currently unclear. According to Jetelina, it’s possible the drug doesn’t sufficiently clear the virus in some people, so once the patient stops taking it after the fifth day, the microbe can start multiplying again.

It may also be that rebound happens when treatment is started too early; current recommendations call for initiation as soon as possible, ideally within the first five days, but that may not give the immune system time to mount a full response. It’s also possible that some people had been reinfected after their illness ended, although this wouldn’t explain rebound cases in people who hadn’t had any additional exposure after recovering.

According to Pfizer spokesperson Kit Longley, rebound is not caused by the virus becoming resistant to Paxlovid, although he notes that the company continues to monitor the data. In a report posted online in June but not yet published in a medical journal, Pfizer researchers describe details from their original study, in which rebound was not linked to any mutations occurring in the virus in people taking the drug.

This is consistent with research published in June by a team at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. That team performed detailed antiviral sensitivity and neutralizing antibody testing on a single rebounding patient. They concluded the relapse was not caused by drug resistance or by impaired immunity, but instead likely resulted from the virus having insufficient exposure to the drug.

Who is at greatest risk of rebounding and what should you do?

Who might rebound—and what they should do about it—are also open questions.

In the Case Western Reserve research, people with the most serious medical conditions, such as organ transplant recipients, those on immunosuppressant medicines, those with comorbidities like heart disease or diabetes, and tobacco users were most prone to COVID-19 rebound.

Of course, this is also the group most likely to reap the benefits from taking an antiviral.

Taking an antiviral also seems to be especially important for high-risk individuals over age 65, according to an Israeli study of more than 2,000 people that has not yet been reviewed by other scientists. People in that age group treated with antiviral therapy were 67 percent less likely to be hospitalized and 81 percent less likely to die than those not taking the drug, a finding not found for the younger study subjects.

If someone does experience rebound, the CDC says they should assume they’re infectious and begin another round of five-day isolation, followed by five days of masking. However, the agency admits that no one knows yet whether a person’s infectiousness during rebound differs from that during their initial bout.

Some doctors say rebound patients can leave their homes as soon as an antigen test again comes back negative. But Yale’s Roberts thinks it’s imprudent to end isolation early no matter the test results. “Testing errors are frequent, and the lower sensitivity of rapid antigen tests would make me nervous if someone leaves isolation before the allotted time,” he says.

Fortunately, most cases of rebound have been mild. Rebound led to hospitalization in fewer than one percent of cases, according to a CDC study published in June. This makes sense, Roberts says, “since the virus is starting at a lower amount, and the initial drug course allowed time for immunity to build.”

Some doctors are prescribing a second round of Paxlovid—something Fauci says was given to him—but there is no evidence yet to support this expanded regimen. Pfizer’s Longley says the company is currently working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to finalize a study protocol evaluating whether this is beneficial.

It’s also possible that a longer course of the initial antiviral medication, such as seven or 10 days instead of five, might be more effective at blocking replication of the BA.5 Omicron subvariant, which generates higher viral loads than its predecessors, says Jill Weatherhead, an infectious diseases expert at Baylor College of Medicine. She notes, though, that such a protocol would need to be studied before physicians might start prescribing it.

Uncertainties surrounding rebound should not prevent people who could benefit from antivirals from taking them, Roberts insists, even though some patients have told him they want to avoid the drug for this reason.

“This is a dangerous and misguided strategy,” he says. The purpose of an antiviral is to prevent hospitalization and death, not to keep someone from needing to isolate longer.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursDina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?