Why are we afraid of sharks? There's a scientific explanation.

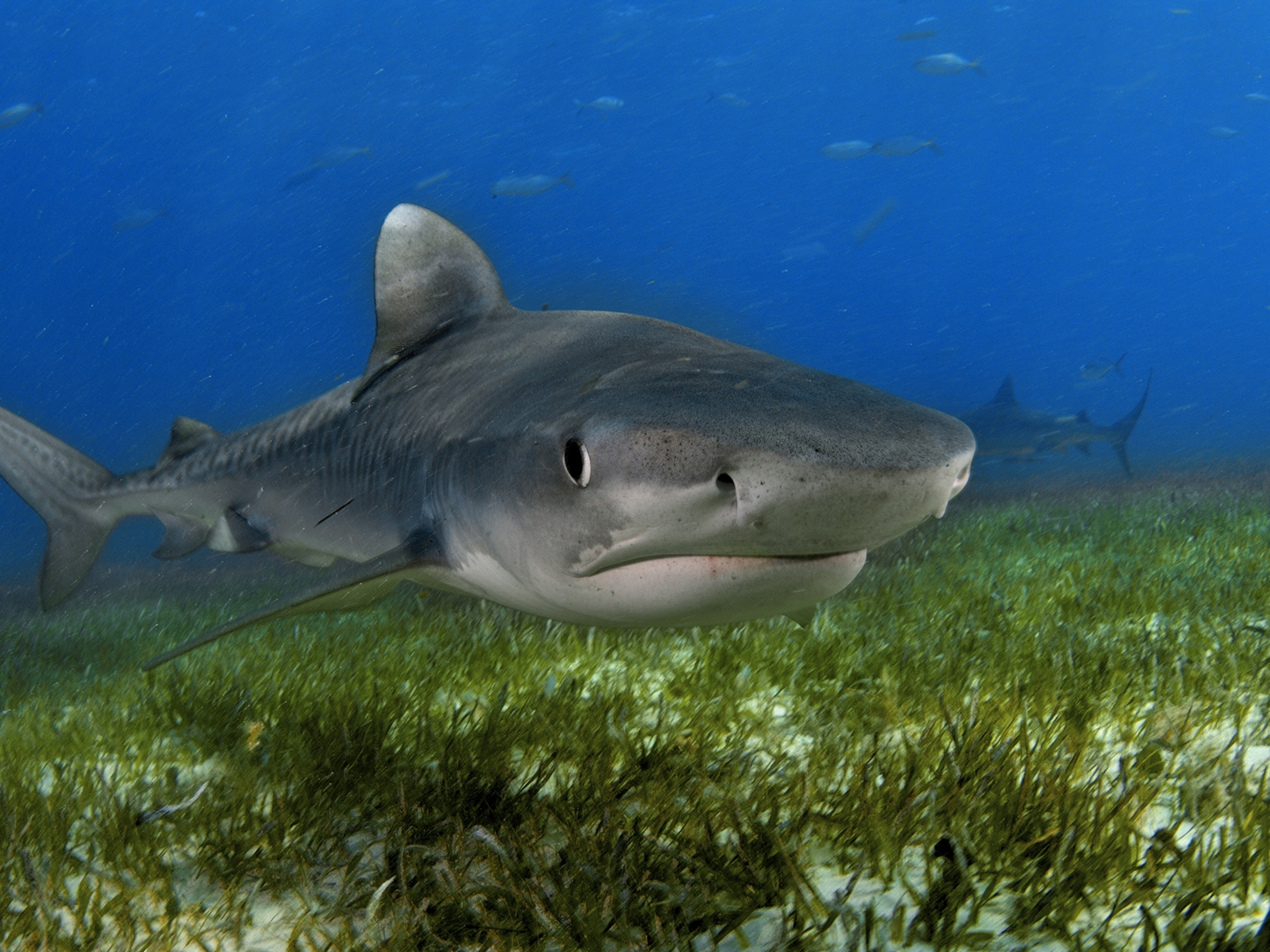

Sharks aren't the mindless killers that we've made them out to be.

Sharks, especially great whites, were catapulted into the public eye with the release of the film Jaws in the summer of 1975. The film is the story of a massive great white that terrorizes a seaside community, and the image of the cover alone—the exposed jaws of a massive shark rising upward in murky water—is enough to inject fear into the hearts of would-be swimmers. Other thrillers have perpetuated the theme of sharks as villans.

But where did our fear of sharks come from, and how far back does it go? That and other shark-related inquiries below.

Why are people afraid of sharks?

"The question implies they shouldn't be," says David Ropeik, a consultant on risk perception and author of the book How Risky Is It, Really? Why Our Fears Don't Always Match the Facts.

A fear of sharks, or galeophobia, is not irrational, says marine biologist Blake Chapman, a shark expert at the University of Queensland in Australia. Simply put, the predatory fish are scary. Great whites, for example—the species Hollywood immortalized as mindless killers—have mouths lined with several rows of up to 300 dagger-like teeth that can easily shred through prey. They can also sense tiny electromagnetic fields put out into water by other animals, which helps them scope out their next meal. (Watch: "World's Deadliest: Shark Superpowers")

But we're not necessarily afraid of sharks upfront, and the animals are diverse. There are more than 465 known species of sharks, and they can range in size from the 7-inch spined pygmy shark to the 50-foot-long whale shark. Many of these cartilaginous swimmers eat fish, crustaceans, mollusks, plankton, krill, marine mammals, and other sharks—in short, humans are not on the menu.

Rather, Ropeik says, we're terrified of how sharks could kill us. Being eaten alive by a 15-foot-long tiger shark seems like a painful way to suffer through death, and we dread the possibility that a shark attack could be the thing that kills us. (Read: "How Tales of Shark Attacks Shaped a U.S. Warship's Legacy")

You're more likely to be crushed to death under a falling vending machine in your office, or a cow that collapses on you in a field than you are to die in the jaws of a shark. But fears don't necessarily match facts, and the fear of being attacked by a shark is more about our emotional response than the reality.

Most of all, we're afraid of losing control. If you're swimming in shark-inhabited water, you don't want the jaws of a mysterious predator to clamp down on you and determine your fate. (Read: "Why Great White Sharks Are Still a Mystery to Us")

"The idea of being munched on by an animal that is in control is another factor," Ropeik says. "It's the nature of the experience, and not the agent, per say."

Where did this fear come from?

Fear is not necessarily something we're born with, but it's something we have developed over time. Infants aren't afraid of snakes and heights, but as adults, our brains become more sensitive to fearful stimuli.

But, oh boy, did our ancestors have a lot to be afraid of! Think back to how ancient people would have survived in their primitive habitats. They would have avoided tall cliffs and wild animals because they knew those threats could potentially kill them, and that's what kept them alive. They learned fear as an adaptation to protect themselves.

"Fear is something that we've inherited from our early ancestors," Chapman says. "[Sharks] are an animal. Biological things like animals are something that we're very prone to fear."

Sharks still seem pretty scary. What are the chances they could kill me?

In writing her book, Shark Attacks: Myths, Misunderstandings and Human Fear, Chapman found that the human brain tends to oversimplify numbers. If I tell you there's a one in 3,748,067 chance you could be attacked and killed by a shark, that number is too abstract for your brain to be sensitive to it. (If I tell you humans kill about 100 million sharks each year, it could be difficult to process that, as well.)

The chances of you being eaten alive by a shark are highly unlikely. You're more likely to die by a dog attack, lightning strike, or car crash. Cancer and heart disease are also way more likely to kill you.

The slim chances that a shark attack could happen to us are irrelevant. We hear of the word "shark" and we can't help but immediately fill in the blank after it with "attack."

"While we can sense fear and we can interpret fear, the actual feeling of fear is completely outside of our control," Chapman says.

OK, but what can I do to fight my fear of sharks?

There are a few ways you can make yourself less afraid of sharks. You can give yourself the illusion of control, because when you don't feel in control, things seem scarier.

To do this, you can read up on what kinds of sharks live in the water you're about to swim in, or learn about which species of shark have been known to go after humans. (Pro tip: blacktip and spinner sharks sometimes mistake humans for prey.)

If you swim in clear water, you can give yourself the illusion of being in control if you did spot a shark. (Great whites can reach speeds 10 times faster than typical humans, so logically, if one of these sharks were to come toward you, you wouldn't have time to escape it. But it's more than likely they would spit you back out.)

To avoid a shark attack, you can also learn how to not be shark bait by avoiding swimming if you're bleeding or lying on a surfboard. (Sharks commonly go after seals, and from below, a surfboard can look like a seal.) You can also avoid spear fishing, because skewering fish sends out electric signals that can attract sharks. (Read: "10 Tips for Sharing the Beach With Sharks")

In the unlikely event that you are attacked by a shark, experts say it's best to fight back. Chapman recommends going for its eyes or gills if possible. If you can give yourself a sense of control, you feel like you're in less danger.

Why is it important we still care about sharks?

Chapman says that yes, the number of shark attacks per year is increasing, but this isn't in line with the skyrocketing human population. Of the 80-odd shark attacks that happen each year, fatality rates are decreasing thanks to improving medicine and medical response time.

It's difficult to count sharks, Chapman says, but it appears their numbers are decreasing. To meet the demand for shark fin soup, some fishermen in Asia will catch sharks, chop off their fins, and then release them back into the water to die. Sharks are also unintentionally caught as bycatch.

The animals are important to oceanic food chains, and sharks keep ecosystems in line. Studies have shown that shark populations can have an effect on sea grass composition and the presence of other animals in a habitat. Sharks are also being studied for cancer treatments and limb regeneration. (Read: "These Sharks Once Ruled the Seas. Now They're Nearly Gone.")

The benefits of having sharks around far outweigh the negatives.

"They are such survivors, they've evolved to basically survive under any stress," Chapman says.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- Spend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the worldSpend a night at the museum at these 7 spots around the world

- How nanobreweries are shaking up Portland's beer sceneHow nanobreweries are shaking up Portland's beer scene

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture