How U.S. vice presidents went from irrelevant to influential

Despite being a heartbeat from the presidency, this role was surprisingly ill-defined throughout much of the country’s history.

Former vice president and presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joseph Biden has announced U.S. Senator Kamala Harris as his running mate in the 2020 presidential election. Though women have been nominated for the vice presidency, Harris is the first Black woman and first person of Indian descent to be nominated by a major political party. No woman has ever been elected vice president.

At any moment, the vice president of the United States could become the world’s most influential leader. But the role of vice presidents has evolved dramatically through the years, from irrelevant throughout much of history to a potential instrument of power today. Here’s what you need to know about the position.

From opponent to running mate

The role of vice president was a governmental afterthought—it was created only at the very end of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, which relegated it to a committee that handled unfinished business. The founders had planned to let the Senate leader—elected by the body itself—assume the presidency if the president were incapacitated.

But then the convention devised the Electoral College, composed of representatives from each state who would convene every four years to elect a president. The founders feared that state loyalties would never produce a frontrunning candidate under this system. In order to reduce the danger of deadlock, they required each elector to select a presidential candidate from a different state. The candidate with the most votes would become president; the runner-up would become vice president. (Here's the difference between a caucus and a primary election.)

The Constitution conferred few powers on the vice president. They would preside over the United States Senate, serve as a tie-breaking vote, oversee impeachment trials, and supervise the counting of the Electoral College’s vote.

But the system swiftly broke down. As political parties emerged, presidents were paired with vice presidents who were diametrically opposed to their politics and who actively worked against them. The parties tried to rectify that by establishing a system of running mates. That backfired too when running mates Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes for president in 1801. The fiercely partisan House of Representatives deadlocked 35 times before breaking the tie, giving the presidency to Jefferson.

Shaken by the constitutional weakness the election exposed, in 1804 Congress passed the 12th Amendment, which gave the Electoral College separate votes for presidents and their running mates. But electing a vice president remained a challenge. In 1837, some electors refused to vote for presidential hopeful Martin Van Buren’s running mate Richard Mentor Johnson, who became the only VP in history to be elected through a 12th Amendment provision that requires the Senate to pick a vice president between two contenders if neither receives a majority of electoral votes.

A vaguely defined role

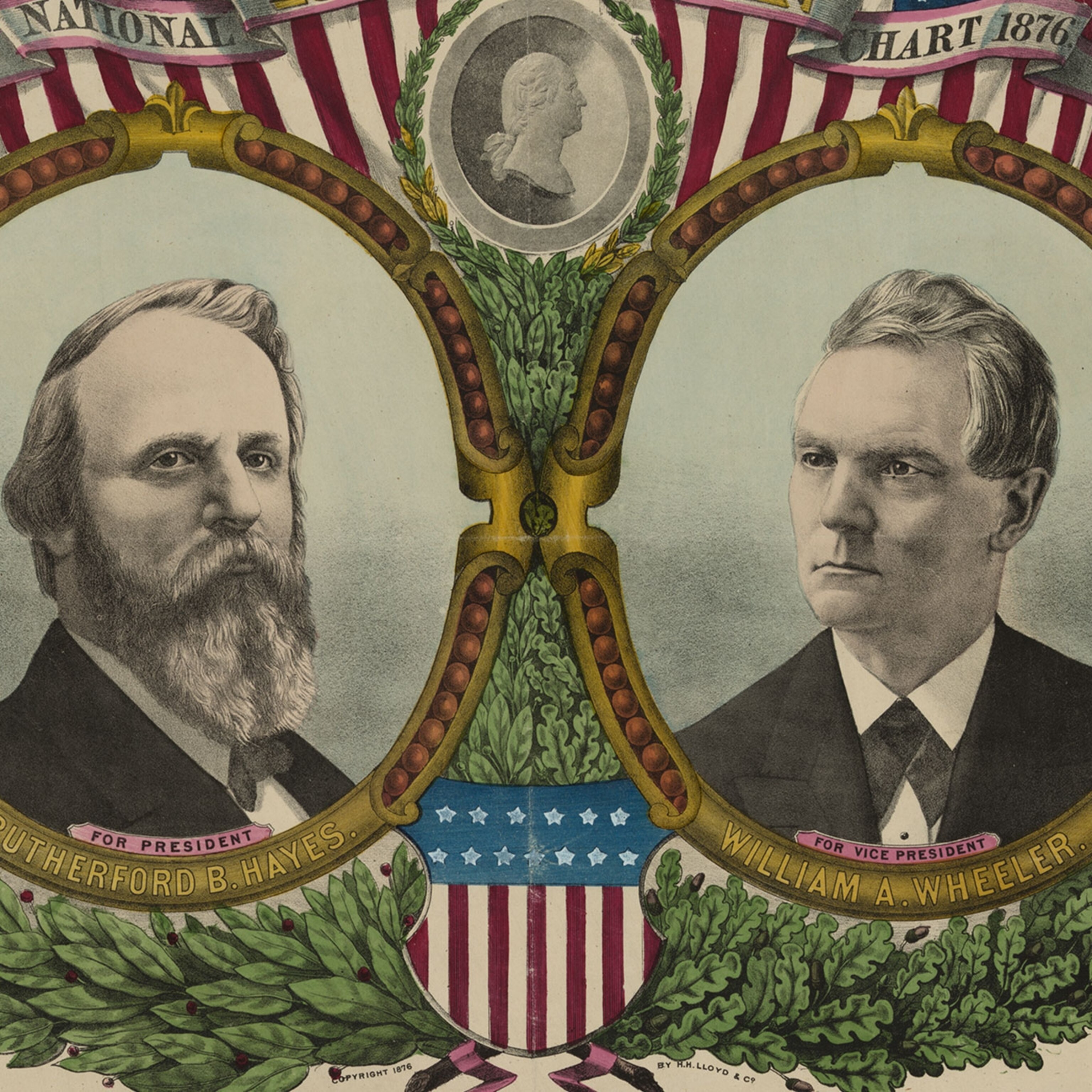

Throughout the 19th century, vice presidents were seen as politically expedient during an election, when they could be used to gain critical electoral votes and balance out the geographic appeal of a presidential candidate. But after the election, most were ignored by the presidents they served—and their duties and role of successor to the president were left unclear.

Part of the problem was the Constitution itself, which vaguely provided that the duties of the president would “devolve” on the vice president if a president became incapacitated or died—but didn’t technically say that the vice president would take over the office. Nor was there a plan for replacing a vice president unable to finish a term.

This was put to the test when President William Henry Harrison died while in office in 1841. While political adversaries argued Vice President John Tyler should only become an “acting” president, Tyler construed the Constitution as giving him not a set of duties but the presidential office itself. He moved into the White House, took a presidential oath, and delivered a brief inaugural address. It would take until 1967 for the precedent he set to be enshrined in the Constitution with the 25th Amendment.

Three other vice presidents assumed the presidency after the untimely death of their predecessors in the 19th century. A few ran unsuccessfully for president. But in the hundred years since Thomas Jefferson’s election in 1801, only one, Martin Van Buren in 1836, made it to the office through an election.

Then came Theodore Roosevelt, who served under William McKinley in 1901. Put on the ticket by New York political rivals who were desperate to unseat him as governor of the state, Roosevelt saw the role as uninspiring but ran because he knew it might give him a shot at the White House. Once installed, he spent his time in office trying to line up an eventual presidential victory. When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt succeeded to the presidency; in 1904, he was elected in his own right. (Inside the 18th-century contest to build the White House.)

Vice presidential power grows

In the 20th century, presidents became more involved in the selection of their vice presidents and gave them more power. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected to his first of four terms in 1932, invited all three of his vice presidents to cabinet-level meetings, a then unprecedented move. Still, Harry Truman, who had become vice president in January 1945, felt almost entirely unprepared to assume the presidency after FDR’s death a few months later.

“I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me,” Truman later said of Roosevelt’s death, which left him to deal with issues like the nuclear bomb, the potential of a Cold War, and the end of the war in the Pacific—issues on which he’d never been briefed.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who succeeded Truman in 1953, was horrified by his predecessor’s unpreparedness. So he made sure his vice president, Richard Nixon, was intimately involved in executive life. Eisenhower included Nixon in meetings and gave him important assignments, like a lengthy trip to Asia and critical civil rights legislation. In part because of his ill health, Eisenhower made arrangements for Nixon to be fully responsible for the presidential role should he become incapacitated.

By the 1960s, it was clear Congress would need to clear up the vague role of vice president. In 1963, Eisenhower’s successor, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated, which left the role of vice president vacant for months after Lyndon B. Johnson assumed the presidency. In response, Congress passed the 25th Amendment, which lays out a procedure for procuring a replacement vice president and resolved, once and for all, that if a president dies or becomes incapacitated the vice president becomes president instead of simply taking over the duties. (Do you know all of these presidential fast facts?)

Modern media frenzies and higher-profile candidates

Recent history has turned the selection of a potential vice president into a predictably press-friendly event. As campaigns have become more media savvy, the selection of vice president has become part of campaigns’ media strategies.

In 1972, Democratic nominee George McGovern had been turned down by multiple would-be vice presidentVPs, and his eventual pick, Thomas Eagleton, quit the race after news reports revealed he had received electroshock therapy during a psychiatric hospitalization.

McGovern’s failure to vet Eagleton was derided by Republicans, and, four years later, Carter’s campaign took it as a lesson. In 1976, it mounted the first public vice presidential vetting process and didn’t reveal his pick until the nominating convention—setting off speculation in the media. These theatrics were a PR coup that has been repeated by other campaigns since.

As a result, modern vice presidents have gained higher profiles and are often selected to widen a presidential candidate’s appeal or to balance out perceived political or policy deficiencies. In the 1980s George H.W. Bush was tasked with forming vital relationships with heads of state and international dignitaries. His vice president, Dan Quayle—a former representative and senator who was chosen to balance Bush’s appeal to older voters—served as the president’s go-between with Republican legislators.

Other vice presidents focused on creating policy. Under President Bill Clinton, Al Gore was a powerful advocate for the environment and brokered a last-minute agreement in Kyoto, pledging reduced emissions on the part of the United States. (Legislators never ratified the treaty in the U.S.) Richard Cheney was seen as reinventing the vice presidency by taking on a greater role in President George W. Bush’s policy development.

While much has changed about about the vice president’s role through the years, some things have remained the same: Only white men have ever served as vice president—and only two women, Democrat Geraldine Ferraro in 1984 and Republican Sarah Palin in 2008, have ever been nominated to the office by a major political party.

Vice presidents also still attempt to use the role as a springboard to the presidency—though the last to succeed was George H.W. Bush in 1989. In the nearly 250 years since the country’s founding, only 14 vice presidents have gone on to become president, either through their predecessor’s death or resignation or by election.

The vice presidency has long been what the officeholder is willing to make of it. And though little is certain in politics, the office is sure to continue to evolve alongside the republic the vice president serves.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital

- Want to travel like a local? Sleep in a Mongolian yurt or an Amish farmhouseWant to travel like a local? Sleep in a Mongolian yurt or an Amish farmhouse

- Sharing culinary traditions in the orchard-filled highlands of JordanSharing culinary traditions in the orchard-filled highlands of Jordan