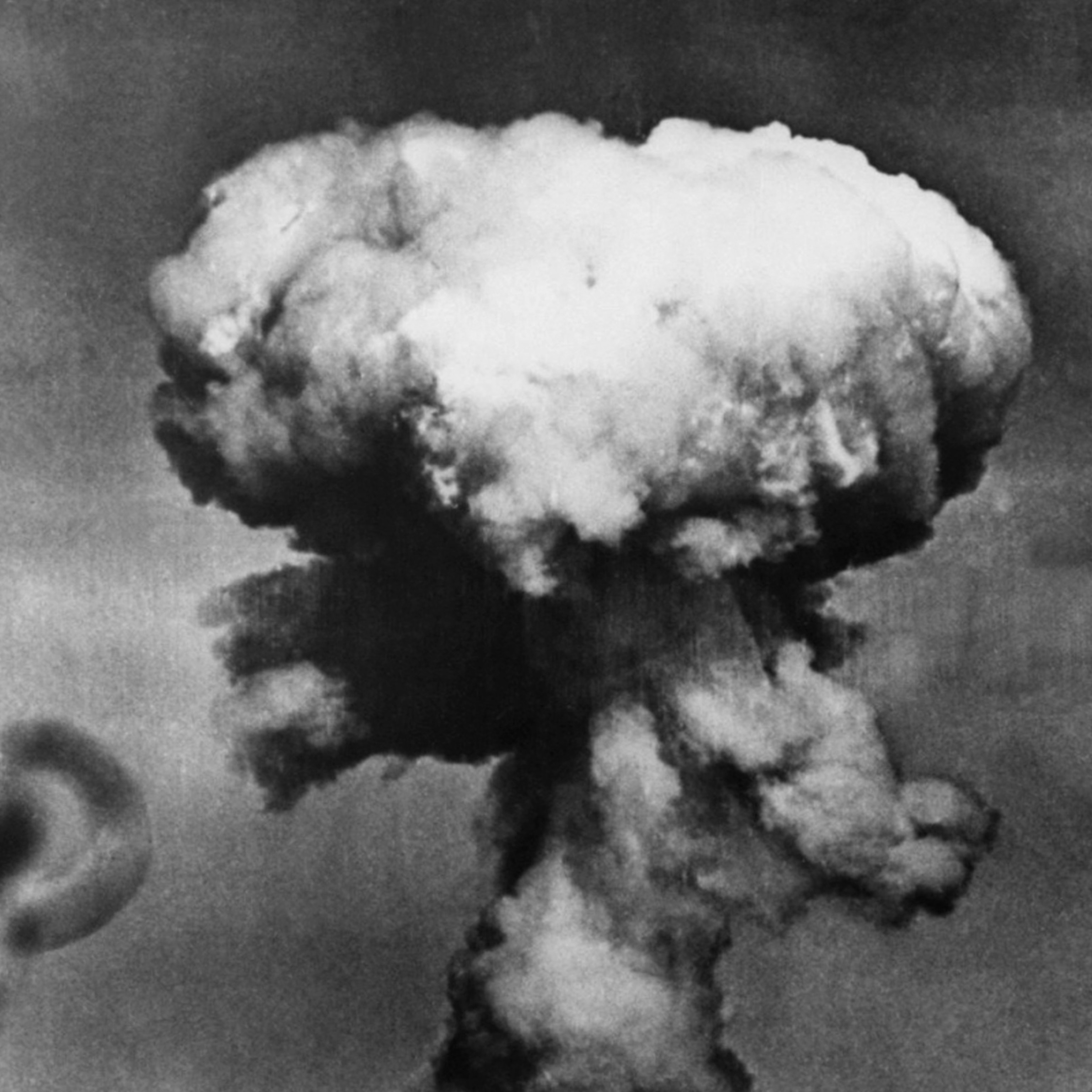

The bombing of Hamburg foreshadowed the horrors of Hiroshima

Operation Gomorrah was the first time Allied forces targeted civilians—using an innovative technology that rendered German radar all but useless.

Paul Peters staggered out of the bunker, driven into the Hamburg street by the increasing heat bomb after bomb had inflicted on his apartment building. As people rushed outside, they were hit with hurricane-force winds, flying sparks, and burning debris.

It was 1943, and the attack the Allies codenamed Operation Gomorrah had transformed an orderly harbor city at the heart of the German war machine into a living hell.

“The firestorm was so strong that hats were torn off heads and whirled through the air like burning fireballs,” he later wrote in an eyewitness report. “Even little children, running around alone, were bodily picked up from the ground and thrown through the air.” Though Peters survived the night’s air raid, his wife did not. (75 years after the Nazis surrendered, all sides agree: War is hell.)

Named after the Biblical city God was said to have destroyed with fire and brimstone, Operation Gomorrah was an eight-day, seven-night bombing campaign designed to level Germany’s second-largest city. It marked the beginning of a new phase of World War II, one in which the Allies would begin targeting civilians in a concerted effort to crush German morale and put an end to the war. It was also the first use of an innovative new technology that rendered radar all but useless.

Why “precision bombing” was anything but

Targeting civilians was an idea that Allied leaders found distasteful at the beginning of the war. Despite initial losses and Nazi Germany’s demoralizing Blitz bombing campaign against London in 1940 and 1941, they at first resisted calls to give the Germans a taste of their own medicine. “My dear sir, this is a military and not a civilian war,” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously told an MP who had called for swift retribution for the Blitz.

But by 1943, that take was becoming less popular. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had adopted a “precision bombing” strategy involving daytime raids on military and industrial targets and nighttime leaflet drops over German cities. But the strategy was thwarted by the imprecision of British pilots’ equipment and the dangers of raids in broad daylight. Heavy casualties ensued.

The RAF then turned to nighttime bombing. But British bombers weren’t made for night flights, and blackouts and German antiaircraft weapons made precision bombing all but impossible. One internal report found that only one in five bombers dropped its payload within five miles of its target.

The rise of “area bombing”

It was time for a change in tactics—and a controversial strategy known as “area bombing.” The concept was simple: Instead of bombing specific targets, Allied bombers would focus on targets and surrounding civilian areas. With this new strategy, the Allies had decided that their enemy was not just Adolf Hitler or the German military, but German morale.

Despite their initial hesitance, Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed on to a new plan to target and destroy German cities. Their reasoning? Perhaps one or two unprecedented attacks would be enough to end the war. There were two other upsides for the Allies: A big area bombing victory would both eliminate criticisms of the Allies’ imprecise bombing capabilities and help the U.S.S.R., which had been attacked by Nazi Germany in the east.

As the Allies began shoring up their ability to bomb a German city, they took lessons from the Blitz that had so shaken Londoners. After noticing that Brits whose homes were struck by bombs were less likely to show up to work, analysts determined that destroying Germany’s largest cities and towns would likely cripple Germany’s war efforts. And they decided to drop incendiary bombs designed to start fires alongside traditional explosives after seeing how much damage German incendiaries had done in London.

They conducted extensive tests to determine how to take advantage of the fires started by those bombs. The goal was to harness fire’s tendency to perpetuate itself, building on dry weather conditions and other factors in the hopes of overwhelming emergency responders and burning as much territory as possible.

Now all the Allies needed was a place to stage the tactic’s big debut. They found it in Hamburg. A major center of both inter-European and international trade, Hamburg was a mainstay of German military might. The U-boats and other ships that made Germany such a dangerous foe at sea were produced there, and its 1.5 million inhabitants made critical contributions to the war effort.

Foiling German radar

The very factors that made the harbor city a prime target made it a treacherous one. Hamburg had been on high alert throughout the war, equipped with massive flak towers packed with antiaircraft guns, and guarded by the most modern radar technology.

But Allied strategists had a secret weapon up their sleeve: a new technology code-named “Window.”

Invented by British scientist Joan Curran, Window was a tactic now known as radar chaff. The idea was to create false signals on German radar screens by throwing down paper strips coated in aluminum alongside the bombs. When a radar-generated radio wave hit those hundreds of shiny strips, it reflected their energy back to the radar screen. That reflected energy would seem to radar operators like a large object, fooling them into targeting what was actually dead air. Window created a virtual smokescreen that rendered German radar all but useless.

Operation Gomorrah begins

At approximately 1 a.m. on July 24, 1943, the first bombs of “Operation Gomorrah” fell. In the days that followed, hundreds of British and American planes flew over Hamburg. British planes focused on night raids while Americans flew by day.

As British bombs fell into the city, sheer chaos erupted on the ground. Confused by the chaff, the German air force sent pilots on pointless missions while searchlights scanned the sky aimlessly and on-the-ground gunners fired seemingly at random. And that was just the first night.

Over the days and nights that followed, the raids came again and again. Citizens tried their best to extinguish the flames that were destroying entire city blocks, but their efforts were mostly in vain. Contemporary reports include descriptions of blinding flames, panicked civilians, and collapsing buildings.

Just as the Allies had planned, a combination of weather and explosives created the perfect fire conditions. Hamburg was in the throes of an unusually dry summer, which turned its wood structures into tinder.

The firestorm

The worst night was July 27, when an unprecedented firestorm overtook the city. Winds reached speeds of 170 miles per hour and street temperatures rose to at least 1,400 degrees, enough to melt glass and asphalt. The rapidly rising air fueled an inrush of new oxygen, further fueling the fire. The oxygen was literally sucked out of basements and air raid shelters and replaced with carbon monoxide and smoke, suffocating inhabitants.

Civilians scattered, disoriented and terrified, dodging falling buildings and dead bodies as their own clothing burned into their skin. As Hamburg resident Heinrich Johannsen huddled under a wet blanket with his son in a pile of gravel at a construction site, he “saw many people turn into living torches.” In basements and air raid shelters, bodies simply disintegrated into ash. The shrieking storm sent billows of smoke 20,000 feet high; from above, British pilots reported the smell of burning flesh. (WWII’s brutality still haunts the children who survived it.)

When the flames finally died down a week after the first bombs fell over Hamburg, the magnitude of destruction was like nothing the world had ever seen. A total of 9,000 tons of bombs had been dropped, and at least 37,000 people were dead. More than 60 percent of the city’s housing was gone. It had been the most destructive battle of the war thus far. In the days that followed, nearly a million people fled Hamburg; meanwhile, concentration camp prisoners were brought to the city to dig graves and clean up.

Germany was stunned. Although Nazi officials publicly accused the Allies of war crimes and milked the bombing for propaganda value, they were privately shaken. Meanwhile, the campaign was praised by the Allies as a much-needed success.

Was Operation Gomorrah justified?

The Allies’ willingness to decimate an entire city—and tens of thousands of its civilians—presaged not just their eventual victory but also the firebombing of Dresden and the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Nor did the Allies stop targeting Hamburg, whose war industry largely recovered within months. (For Hiroshima’s survivors, memories of the bomb are impossible to forget.)

But area bombing’s fiery debut still generates debate among historians, who wonder whether the tactic was justified by Germany’s commitment to total war—and whether it truly achieved its objectives. The hoped-for destruction of German morale never materialized. Instead, the bombings revealed the resiliency of the German people and the Nazi state’s determination to fight to the bitter end.

After the war, Nazi minister for armaments and war production Albert Speer told interrogators that the firebombing of Hamburg “made an extraordinary impression” on Hitler’s closest advisors and that he’d advised Hitler similar Allied attacks “might bring about a rapid end to the war.” They didn’t: After Operation Gomorrah, the Nazis doubled down on their military objectives even as civilians suffered.

Historians also question the Allies’ decision to continue targeting civilians for the remaining two years of World War II—even when it was clear Germany was on the verge of defeat. The Allies had bombed Hamburg in the belief they could stop the bloodshed. But the firestorm they created couldn’t burn out the will for war.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads