On a warm summer evening several years ago, congregants jammed the front of the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tennessee. It was homecoming time, and scores of Pentecostals, hailing from throughout Appalachia, had gathered to worship God in a ritual that risked bodily harm.

Dancing around the pulpit, Tyler Evans, whose family has handled serpents for five generations, held a Coke bottle with a flaming wick to his skin, a practice called “handling fire.” The teenager suffered no burns. Next, he took a swallow from a Mason jar containing a mixture of water and strychnine—a bitter poison made famous in Agatha Christie novels. He let out nary a cough. From a few feet away, Pastor Andrew Hamblin nodded in approval. On his arms dangled two venomous copperhead snakes, mottled in brown and tan.

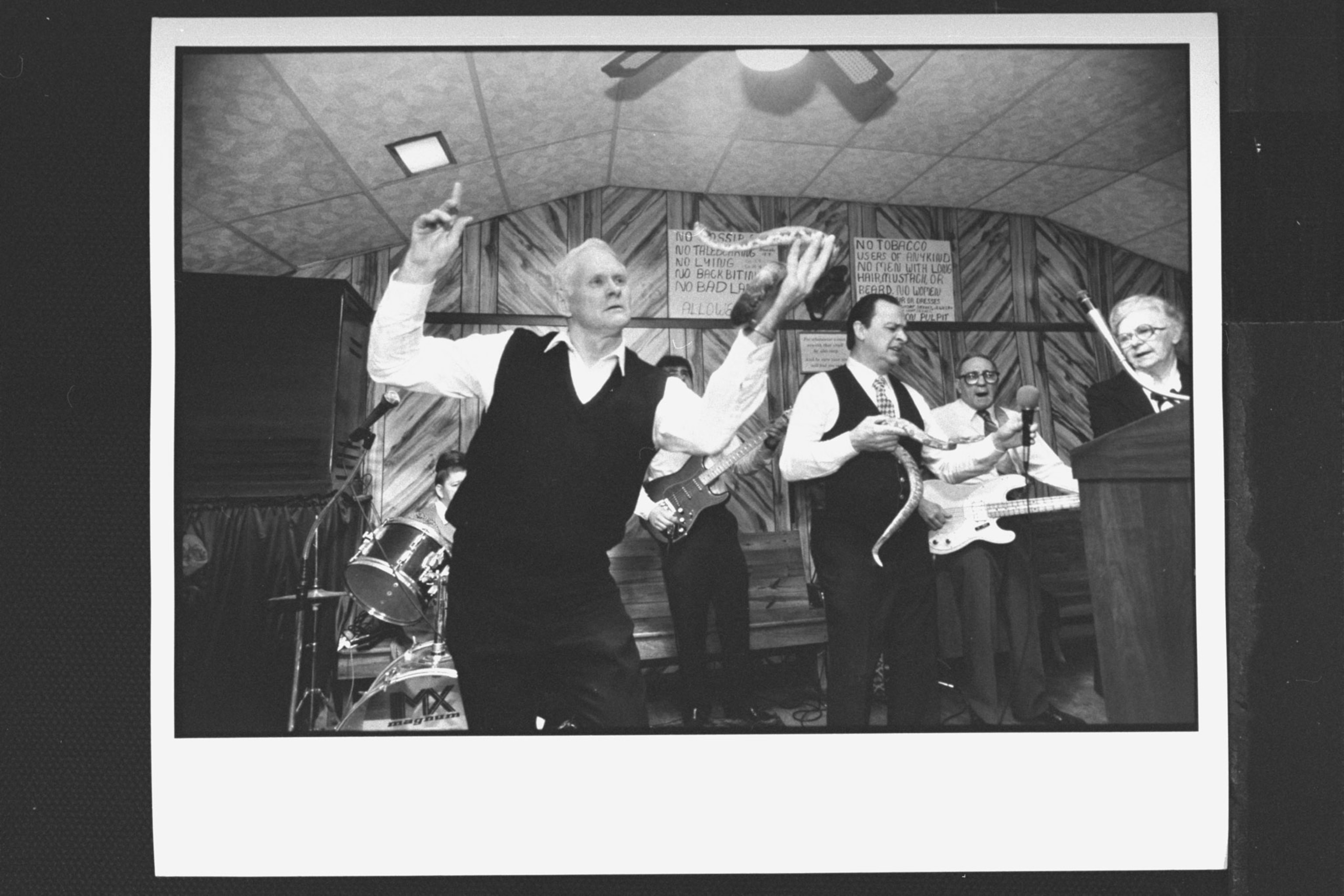

Six Appalachian states, including Tennessee, outlaw religious snake handling on a variety of grounds, but Hamblin’s enthusiastic congregation paid no mind to such strictures. Men in dress shirts and black pants linked arms around each other’s shoulders and shuffle danced, forming and reforming circles as they wove across the pulpit’s small platform. Praying and singing, they passed sharp-fanged serpents from hand to hand or waved them slowly in the air.

For Andrew Abrams, 18, the evening was an initiation. He’d been praying for a sign from God when his father approached him with two copperheads. “Lord, I can’t do this,” Abrams said he immediately thought. But he accepted the sinuous creatures. “There’s no feeling like that on Earth,” he said with a grin afterward, “knowing you’re holding death in your hands and it won’t do anything to you.”

“They shall take up serpents”

The Tabernacle Church of God has since closed, but at the time it was one of roughly 125 churches in the United States that follow the “signs” described in chapter 16 of the Gospel of Mark:

And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues;

They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

In other words, those who believe the word of God and preach the Gospel will be empowered to send demons packing, speak in unknown languages, heal by laying on hands, and—like the young men in Hamblin’s congregation—safely drink poison and handle venomous snakes.

The roots of modern-day Pentecostalism lie in the “Holiness” revival of the late 19th century, when Methodists, with sprinklings of Anabaptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, demonstrated their devotion to God by avoiding worldly pursuits like dancing, drinking, gambling, and attending the theater. Many scholars trace the birth of the modern Pentecostal movement to a prayer meeting held in Topeka, Kansas, on the first day of 1901, where congregants resurrected one sign—speaking in tongues—after nearly 2,000 years of disuse. Laying hands on the sick and casting out demons soon followed. Adherents would not drink poison or take up snakes, however, until several years later, when George Hensley, a Tennessee revivalist, popularized bringing reptiles into his church, convinced that the Bible mandated following all five signs.

Most Pentecostals denounced this interpretation, which is why the practice is confined mostly to remote Appalachian chapels in backwoods hollows, far from the gaze of other Christians and law enforcement. Hamblin preached, however, just six miles from Interstate 75.

He was different in other ways, too. While old-timers in this movement avoided such vices as smoking and swearing, dressed modestly, eschewed divorce, and never spoke to reporters, Hamblin openly enjoyed cigarettes, never insisted on a dress code, and welcomed media. His congregation was just as likely to include grandmothers in floor-length skirts and chignons as recovered drug addicts and women in denim, rhinestones, and white leather boots. Ironically, it is this latter group—younger and far more worldly—that now breathes new life into this controversial practice.

“They call this the Land of Misfits Church,” Michelle Gray, who’d driven 90 miles to attend the homecoming, told me. “People with a past come to Andrew’s.” Gray introduced her teenage daughter, Madison, who’d just started handling snakes, an experience she described as “overwhelming and exciting.”

For sure, she’d be coming back.

Shifting interpretations

I first met Hamblin at the close of 2011, at a New Year’s Eve service where, almost at the stroke of midnight, a timber rattler sunk its fangs into the pastor’s index finger. Fortunately the bite was dry, meaning little or no venom was injected. Meeting with Hamblin the next day, I was impressed enough with the then-20-year-old to profile him for the Wall Street Journal. That story was followed by a contract for a reality show on the National Geographic Channel, in which he would star alongside Jamie Coots, the Kentucky pastor of the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus’ Name, not far from LaFollette.

By mid-February 2014, Coots, who had been a mentor to Hamblin, had fallen victim to a timber rattler’s bite. Hamblin helped officiate at his funeral, an emotional affair that attracted national media attention and serpent handlers from several states. They wanted to pay their respects to someone who had rejected medical intervention and died while practicing the signs—the ultimate form of faithfulness to the Gospel of Mark.

But while Coots’ death valorized a tradition for many observers, it represented a sea change for Andrew Hamblin. “Since Jamie died,” he told me, “I’ve offered a rattler to no one. I am the shepherd, and I am responsible for what happens in this building.”

But that’s not the only way in which his views and practices have evolved.

For generations, serpent-handling Pentecostals have captured their own snakes—mostly timber and canebrake rattlesnakes, plus the occasional diamondback rattlesnake, cottonmouth, or copperhead that inhabit the Southeast. More recently, handlers have been known to buy exotics, including cobras and Asian vipers, at reptile shows in South Carolina, which doesn’t restrict sales of venomous snakes.

Handlers usually keep their animals in terrariums or cages in sheds, feeding them live mice about once a week. But the animals are often treated poorly, according to Kristen Wiley of the Kentucky Reptile Zoo, which sometimes ends up caring for—or euthanizing—weak and dehydrated snakes confiscated from Pentecostal handlers.

Handled gently, reptiles are unlikely to bite, and weak snakes can’t inject a lethal dose of poison. But the more one handles, the greater the likelihood of bites. Rattlesnake venom, which contains hemo- and neurotoxins, induces numbness and swelling, blurred vision, paralysis, and respiratory failure. It destroys skin tissue and blood cells, leading to internal hemorrhage. Victims can survive if they receive antivenom within two hours, but without medicine, death can occur within six to 48 hours. (Related: Africa’s antivenom shortage contributes to tens of thousands of deaths each year.)

Until quite recently, signs-following snake handlers rejected medical care because it demonstrated a lack of trust in God’s healing powers. But in the years that have passed since Coots’ death, many younger serpent-handling preachers, Hamblin among them, have changed their minds on this defining theological point.

Now, says Ralph Hood, a University of Tennessee professor who specializes in the psychology of religion and has long studied serpent handlers, refusing to call 911 is considered by some to be old school, and pragmatism rules. Yes, the Gospel of Mark encourages serpent handling, say younger pastors, but no verse forbids seeking help for serious bites.

“Little Cody” Coots, the 28-year-old son of the late Jamie Coots, typifies this newer way of thinking. During a June 2015 church service, Coots had draped a timber rattlesnake, as thick as a soda can, halfway down his back as congregants shouted and a piano tinkled. “I believe in the Lord God Almighty, and if he says I can hear him, I can!” Coots bellowed into the microphone. But after he shifted the snake toward his chest, the reptile lunged at his head, striking the artery near his right temple.

With blood spurting over his pale blue shirt, Coots wilted into the arms of his friends, one of whom, according to Hood, asked Coots if he was ready to die. No, Coots said. Helicoptered to a hospital in Knoxville, he was put on life support and eventually recovered.

Then, on Memorial Day weekend of 2019, at the House of the Lord Jesus Church in Squire, West Virginia, an eastern diamondback arched into the air and sunk its fangs into the right forearm of Pastor Chris Wolford. Everything came to a halt as the 46-year-old collapsed, his lips and tongue swelling until he could barely breathe.

It had been seven years—almost to the day—since his older brother, Randy, had been bitten by a yellow timber rattlesnake while conducting a revival at a state park in West Virginia. Refusing to call for an ambulance, he took about 10 hours to die.

Perhaps with that history in mind, worshippers dialed 911.

At the regional hospital, the younger Wolford’s kidneys failed, and doctors sliced open his arm to relieve swelling that constricted his muscles and nerves. After 13 days and multiple surgeries on his arm, Wolford was released. He’s now back in the pulpit and handling snakes, but he won’t comment on his decision to seek medical help.

“I’ve been bit twice by a copperhead, and I didn’t go [to a doctor],” said Jimmy Morrow, 65, the serpent-handling pastor of the Edwina Church of God in Jesus Christ’s Name, in Newport, Tennessee. “I just stayed home, and the Lord healed me. I know a lot of good brothers and sisters who say that when they die, they want to die [while practicing] the signs of the Gospel.”

David Kimbrough, author of Taking Up Serpents: Snake Handlers of Eastern Kentucky, says different doctrines help explain the different approaches. In Kentucky, snake handlers conduct baptisms in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. They’re called “Trinity” believers, and they mostly refuse to visit doctors when bitten by a snake. “If God allows a snake to bite you, they expect everything to go through its natural course,” Kimbrough says.

Farther south, pastors baptize only in the name of Jesus. They are called Oneness Pentecostals, and they are more likely to call for help in an emergency. “People have become more enlightened,” Kimbrough says. “I hear them saying, ‘God gave doctors the ability to cure people, and he wants you to use them.’ Jesus didn’t condemn the physicians.” (Here’s what archaeology says about Jesus.)

But Hood, at the University of Tennessee, believes something has been lost in the compromise. Serpent handlers used to say they drank poison and handled venomous snakes to demonstrate God’s power to protect believers. “What meaning does this high-risk behavior have if you’re allowed to go to a doctor for the outcome?” he asks.

A wider welcome

Andrew Hamblin is now 29 and pastoring, occasionally with snakes, at the Free Pentecostal House of Prayer in the tiny hamlet of Gray, in southeastern Kentucky. He divorced his wife in 2015, leaving her with six children, and started a new family with a second wife. Unsurprisingly, he welcomes those whom other churches might shun.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, it doesn’t matter where you've been, it doesn’t matter what you've done, Jesus is calling!” he announced on Facebook when he opened his new church in the fall of 2019.

Divorce used to be disastrous to a serpent handler’s reputation—especially among Trinity believers. Ditto with remarriage. But that didn’t seem to be an issue for Hamblin’s followers. “He had a crowd the first night he opened,” said Verlin Short, 49, a more traditional handler from Kentucky who was featured in a 2012 Animal Planet reality show. “There’s a lot of preachers who’ve made mistakes, and other churches have not been so forgiving.”

This past Easter Sunday, as churches nationwide sat deserted due to COVID-19, Hamblin preached to a nearly empty building. But he reminded his congregation, through a video posted to YouTube, that the shouting, the praising, and the snake boxes would return. (See all of Nat Geo’s COVID-19 coverage here.)

Recall that Hamblin had, earlier, broken a major taboo by allowing his services to be filmed. The reality show riled many old-time handlers, who felt the program commercialized their beliefs. They preached against the show and have since banned any sort of filming within their churches. “They feel they preach for three hours and handle serpents for five minutes,” says Hood, and the only thing that gets aired are the snakes.

Critics had another gripe: In their hunger for drama, many of the media-friendly handlers no longer waited for “God’s anointing”—a recognition of the Holy Spirit’s presence—before racing to their snake boxes. But there’s more to following signs than handling serpents, Kimbrough warns. The new generation, he says, needs “to focus more on healing, speaking in tongues, and casting out demons.”

Defending the show, Hamblin and Coots noted the many hours they had been filmed preaching the Gospel—inside the church and out. As the episodes aired, Hamblin’s roster of Facebook friends grew to 5,000, and visitors packed his services. Believers asked Coots for prayers, and his church sent out prayer cloths—consecrated fabric—to those unable to attend in person.

Preserving a legacy

After a hundred years, serpent handling remains a spiritual calling, practitioners say, as well as a showcase of God’s power and a way to sustain the legacy of Pentecostal pioneers. But opening church doors to a wider world in the hopes of attracting nonbelievers has been something of a double-edged sword for many of today’s younger snake-handling preachers.

“I’ve been ridiculed, laughed at, and treated like trash by other Christians,” said Jason Stone, who evangelizes from a one-room church in Marion, North Carolina. A genial father of three sons, with curly brown hair and the build of a football tackle, Stone, 40, grew up in a serpent-handling family in southern West Virginia. But last fall he began pulling back from public spectacle, staging snake-handling services only with trusted friends, and only if the Holy Spirit led.

“For me, handling a serpent is like being totally absorbed in the spiritual experience,” Stone said. “You become unaware of everything around you. It’s also a release [from] all negative emotion, which is a part of why I do it.” Stone has never been bitten, and he says he’d have no problem going to a doctor if he were.

Still, Stone’s expectation that handling would help him save souls has, over the decades, shifted. “Back in my twenties, we thought we could spread the Gospel throughout the world,” he said. People would “come to see the snakes, but they’d [also] hear the preaching.” As time passed, he realized he was handling snakes mostly to preserve a tradition, not to convert newcomers.

But then, last December, Stone says he began to receive a vision to open the church in Marion for far larger—and better publicized—serpent-handling services. He hoped to begin, he announced on Facebook, as soon as the pandemic was tamed.

“That would be awesome,” a woman posted. “Please let me know where and when.”

“This sickness will pass,” Stone replied. “We will have plenty of work to do for the Lord.”

Stacy Kranitz was born in Kentucky and lives in the Appalachian Mountains of eastern Tennessee. She is a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow. Her work explores history, representation, and otherness within the documentary tradition. Follow her on Instagram.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

Science

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

Travel

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramid

- Food writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursFood writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches