Giving birth in a time of death: a love letter to my daughter

A photographer turns the camera on her own pregnancy after documenting high mortality rates for Black expectant mothers.

I remember asking my mom what color I was. I knew that I descended from German immigrants on my father’s side and enslaved people on my mother’s side. But the forms at my Tennessee elementary school only listed three options: White, Black, Other.

“I am your mother,” she told me. “You are my child, from my body.”

I didn’t know then what a gift those words were, and how they would root my experience in the world.

As a photographer, I have spent a lot of time documenting reproductive rights, childbirth, and motherhood, often focusing on what it’s like to be pregnant as a Black woman in the American South. I have witnessed heartbreaking moments while doing this work, and beautiful ones, too. So last December, when I found I was pregnant, I thought about all the women who had shared their stories with me over the years.

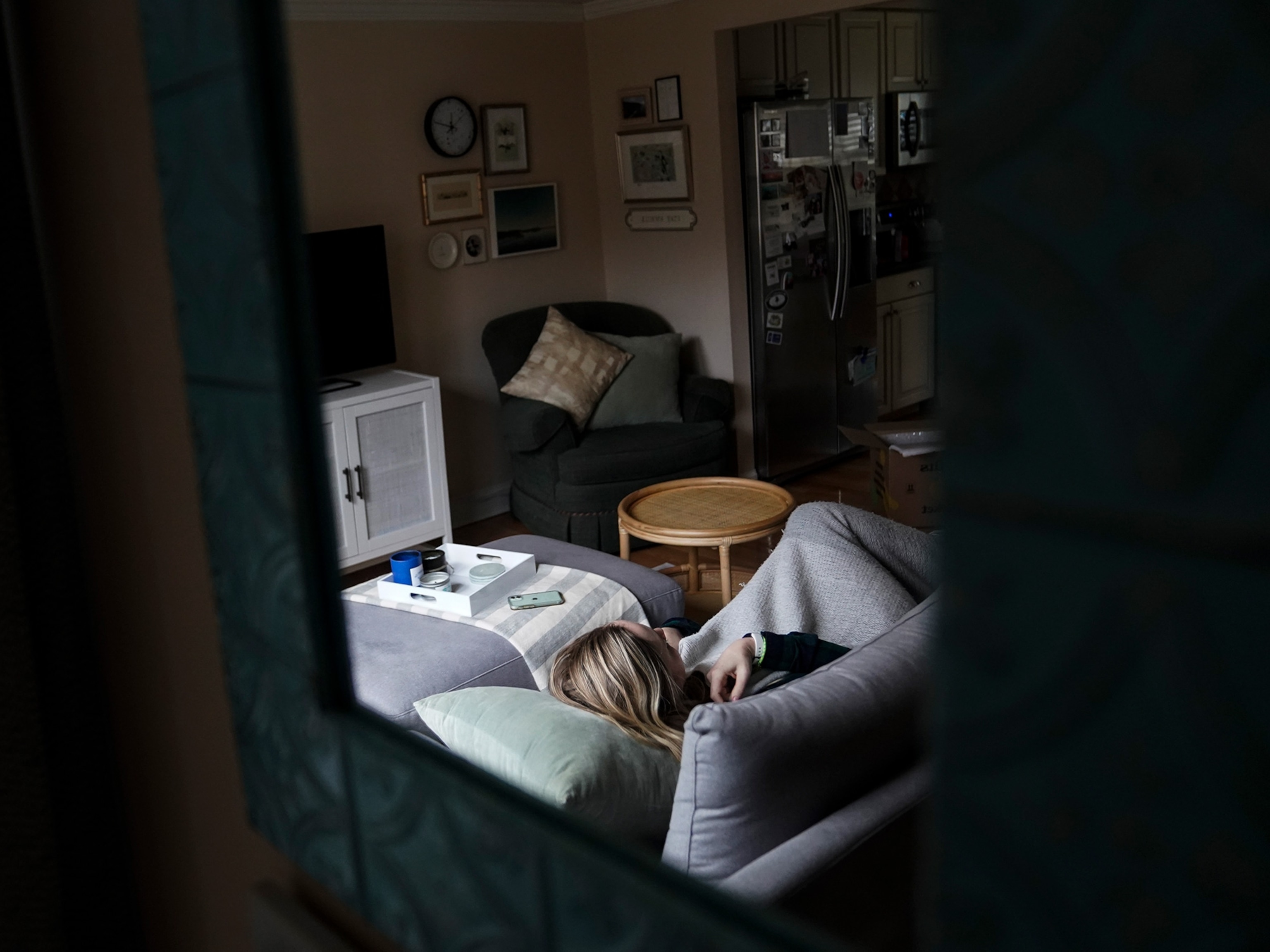

I was busy with work my first trimester and then, just as I entered my second, the pandemic hit the U.S. My brother lives in Hong Kong, so I’d been following news about the coronavirus for a while and had taken some precautions early. I cancelled all my projects and quarantined at home in Los Angeles. I couldn’t photograph other people’s stories, so my husband encouraged me to document my own experience in isolation. I started making photos of our life: my hand hovering above my expanding belly, the cake my husband bought after we forgot our third anniversary. Pregnancy made me feel vulnerable, and the idea of having my firstborn during a once-in-a-generation pandemic made my thoughts spiral. Creating photographs helped me make sense of what was going on.

Because of COVID-19, my in-person appointments turned into phone consultations, which worried me. I thought back to the statistics I’d learned while reporting on maternal mortality rates, knowing that Black women in this country are three times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Black women are disproportionately diagnosed with gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia, and I knew that diabetes ran in my family. What if something had already gone wrong? What if they couldn’t identify it by phone? (Why giving birth in the U.S. is surprisingly deadly.)

I called over and over, asking for an in-person appointment, and eventually the hospital relented. When I finally got to see the ultrasound and hear the doctor say that everything was on track, I felt so relieved. But in that moment, I also wished that my husband was standing next to me in the exam room, not watching through FaceTime in the parking lot.

A few weeks later, Ahmaud Arbery was killed. A familiar despair set in. When George Floyd was murdered a few months later, I realized that I needed to do something to turn this vulnerability into productivity. I started to work again, weighing the risks with each assignment, because I wanted to help document this moment of history that my daughter would be born into. I wanted to teach her, with my actions, how important it is that these stories are told and that they’re told by Black people.

I also spent a lot of time thinking about the kinship among women. I thought about my mom and my sister and how, if we weren’t living through a pandemic, they would have flown to L.A. for a baby shower or my due date. I thought about my doctors—all Black women—and how deeply grateful and comforted I felt knowing they were the ones guiding my pregnancy. I knew from the past what it felt like to have doctors disregard my pain, and I knew that wouldn’t happen this time. I thought about my friends, my community, and what it would feel like to become new parents in isolation—to not have people around us to help, people who years later could tell our daughter that they’d held her when she was a few days old. But I also thought about women throughout history, women who have survived wars, pandemics, miscarriages. Their resilience guided me. (Watch how these women are saving Black mothers’ lives.)

I hoped for a natural birth, but I also wanted to deliver in a hospital in case I had complications.

This proved to be the right choice. After my water broke, my contractions did not start, and suddenly doctors and nurses were peppering me with questions about whether, or when, they’d need to induce me. Did I have strong feelings on the topic, one way or another, they asked. My husband wasn’t allowed in the hospital yet because of the COVID protocols, so I felt a lot of pressure to make the right choice. I was alone and scared and my blood pressure spiked.

Ultimately, labor was induced to keep our baby safe. I had started running a high fever and I was put on antibiotics. Sometimes when I couldn’t take the pain, I pulled down my face mask and gasped for air. Finally, at 9:50 p.m., on a Tuesday in August, our daughter arrived. I had been in labor for more than 24 excruciating hours. (With hospitals full of COVID-19 patients, this New Yorker chose to give birth at home.)

We named her Luna Pearl, after my grandma, Pearl Randolph, a Black woman who raised 11 children, did birthing work in her rural community in Virginia, and invented a way to make school buses safer. I want my daughter, who is a quarter Black, to know the line of women she comes from. I don’t yet know what her experience in this country will be, or how it will differ from mine. But I will teach her that she is a descendant of enslaved people—not slaves, but human beings. Human beings, who in spite of deep oppression, lived in strength and generosity.

“I am your mother,” I will tell her. “You are my child, from my body.” I hope that roots her as it has rooted me.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest