It was the day before Halloween, October 30, 1938. Henry Brylawski was on his way to pick up his girlfriend at her Adams Morgan apartment in Washington, D.C.

As he turned on his car radio, the 25-year-old law student heard some startling news. A huge meteorite had smashed into a New Jersey farm. New York was under attack by Martians.

"I knew it was a hoax," said Brylawski, now 92.

Others were not so sure. When he reached the apartment, Brylawski found his girlfriend's sister, who was living there, "quaking in her boots," as he puts it. "She thought the news was real," he said.

It was not. What radio listeners heard that night was an adaptation, by Orson Welles's Mercury Theater group, of a science fiction novel written 40 years earlier: The War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells.

However, the radio play, narrated by Orson Welles, had been written and performed to sound like a real news broadcast about an invasion from Mars.

Thousands of people, believing they were under attack by Martians, flooded newspaper offices and radio and police stations with calls, asking how to flee their city or how they should protect themselves from "gas raids." Scores of adults reportedly required medical treatment for shock and hysteria.

The hoax worked, historians say, because the broadcast authentically simulated how radio worked in an emergency.

"Audiences heard their regularly scheduled broadcast interrupted by breaking news," said Michele Hilmes, a communications professor at University of Wisconsin in Madison and author of Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952.

Stations then cut to a live reporter on the scene of the invasion in New Jersey. "By the end of the first half of the program, the radio studios themselves were under attack," Hilmes said.

Tuning in Late

Orson Welles and his team had previously dramatized novels such as The Count of Monte Cristo and Dracula. The introduction to War of the Worlds broadcast on CBS Radio emphasized that it was based on the H.G. Wells novel.

But many people didn't hear that introduction. They were tuned into a rival network airing the popular Chase and Sanborn Hour program featuring the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his dummy Charlie McCarthy.

Ten minutes into that show, at a time when its star took a break, many listeners dialed into War of the Worlds instead. Having missed the introduction, they found themselves listening to "the music of Ramon Raquello and his Orchestra," live from New York's Hotel Park Plaza.

In reality, the orchestra was playing in a CBS studio. The dance music was soon interrupted by a series of increasingly alarming news bulletins. An astronomer, played by Welles, commented on reports that several explosions of "incandescent gas" had been observed on the planet Mars.

Then a news bulletin reported that a "huge flaming object" had struck a farm near Grovers Mill, New Jersey. A "newscaster" described seeing an alien crawl out of a spacecraft. "Good heavens—something's wriggling out of the shadow," he reported. "It glistens like wet leather. But that face—it … it is indescribable."

Newspapers vs. Radio

In 1938, with the world on the brink of World War II, audiences were already on razor's edge. The format used in War of the Worlds,with its shrill news bulletins and breathless commentary, echoed the way in which radio had covered the "Munich crisis"—a meeting of European powers that became the prelude to World War II—a month before.

"Welles and his company managed to closely duplicate the style and the feel of those broadcasts in their own program," said Elizabeth McLeod, a journalist and broadcast historian in Rockland, Maine, who specializes in 1930s radio. "Some [listeners] heard only that 'shells were falling' and assumed they were coming from Hitler."

It was also the time during which science fiction developed as a popular genre. "We were on the brink of scientific discoveries about space," Hilmes said. "Dangers lurked abroad—why not in outer space?"

Panicked listeners packed roads, hid in cellars, and loaded their guns. In one block of Newark, New Jersey, 20 families rushed out of their houses with wet towels over their faces as protection from Martian poison gas, according to a front-page article in the New York Times the next day.

But historians also claim that newspaper accounts over the following week greatly exaggerated the hysteria. There are estimates that about 20 percent of those listening believed it was real. That translates to less than a million people.

At the time, newspapers considered radio an upstart rival. Some in the print press, resentful of the superior radio coverage during the Munich crisis, may have sought to prove a point about the irresponsibility of the radio broadcast.

"The exaggeration of the War of the Worlds story can be interpreted as the print media's revenge for being badly scooped during the previous month," McLeod said.

Power of Imagination

There is no doubt that radio held a unique power over its audience. For rural audiences, in particular, it was the primary point of contact with the outside world, providing news, entertainment, and companionship, McLeod noted.

Orson Welles knew how to use radio's imaginative possibilities, and he was a master at blurring the lines between fiction and reality.

"No movie special effects … could have conjured up enormous aliens striding across the Hudson River towards the CBS studios 'as if it were a child's wading pool' [in Welles's words] as convincingly as the listeners' imaginations could," Hilmes said.

War of the Worlds also revealed how the power of mass communications could be used to create theatrical illusions and manipulate the public. Some people say the broadcast contributed to diminishing the trustworthiness of the media.

According to the New York Times, Welles expressed profound regret that his dramatic efforts could cause consternation. "I don't think we will choose anything like this again," he said. He hesitated about presenting it, Welles said, because "it was our thought that perhaps people might be bored or annoyed at hearing a tale so improbable."

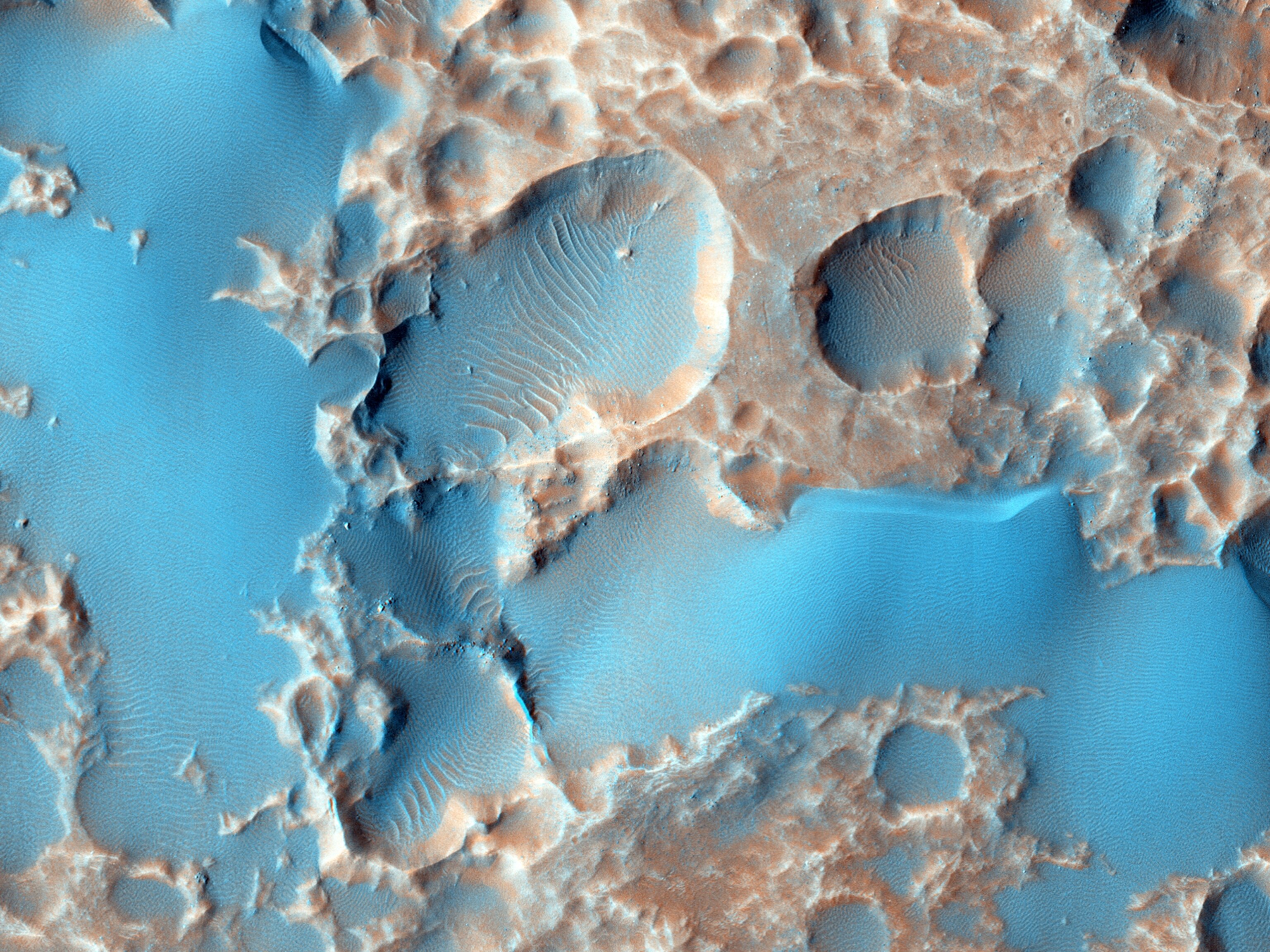

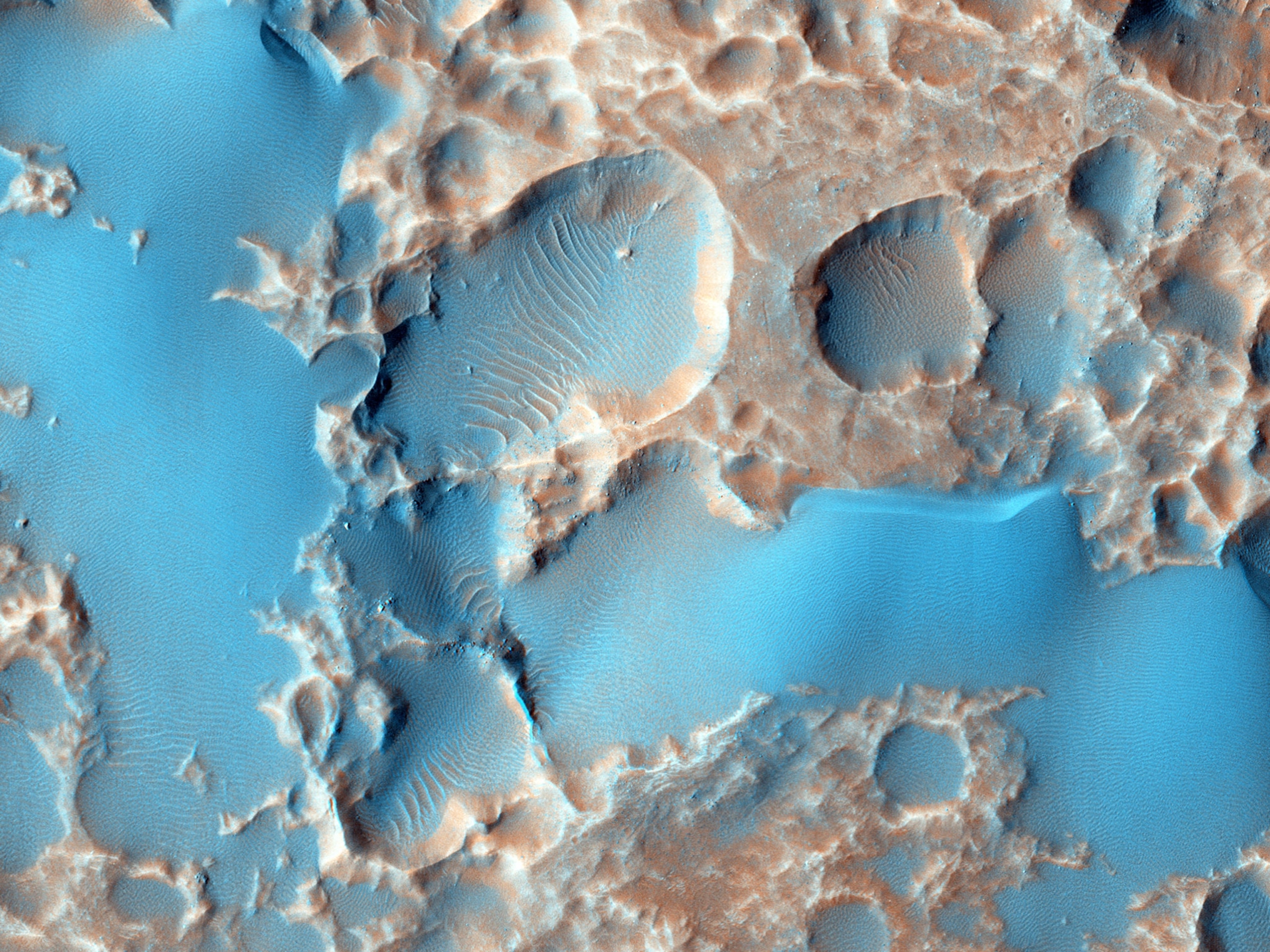

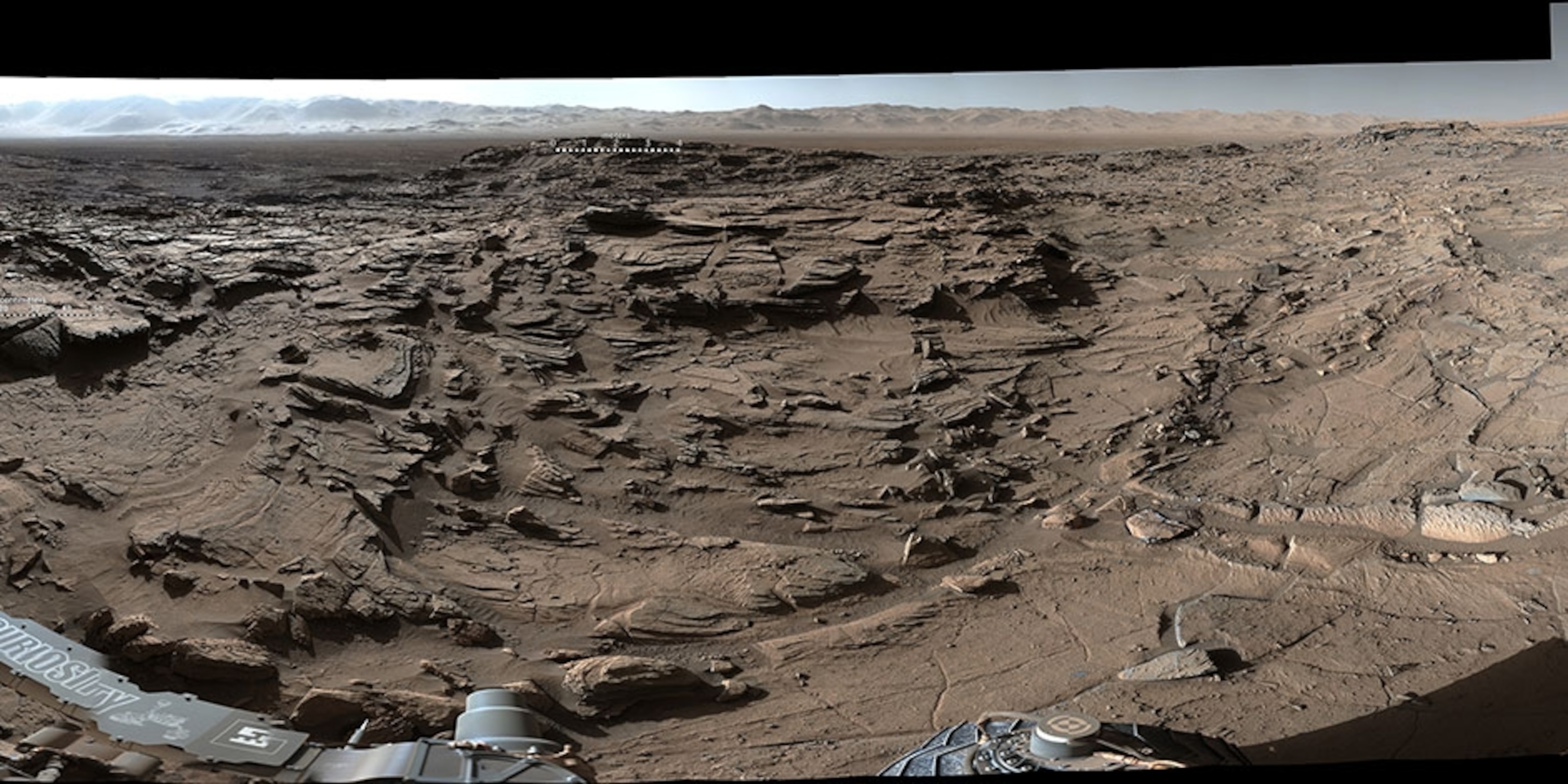

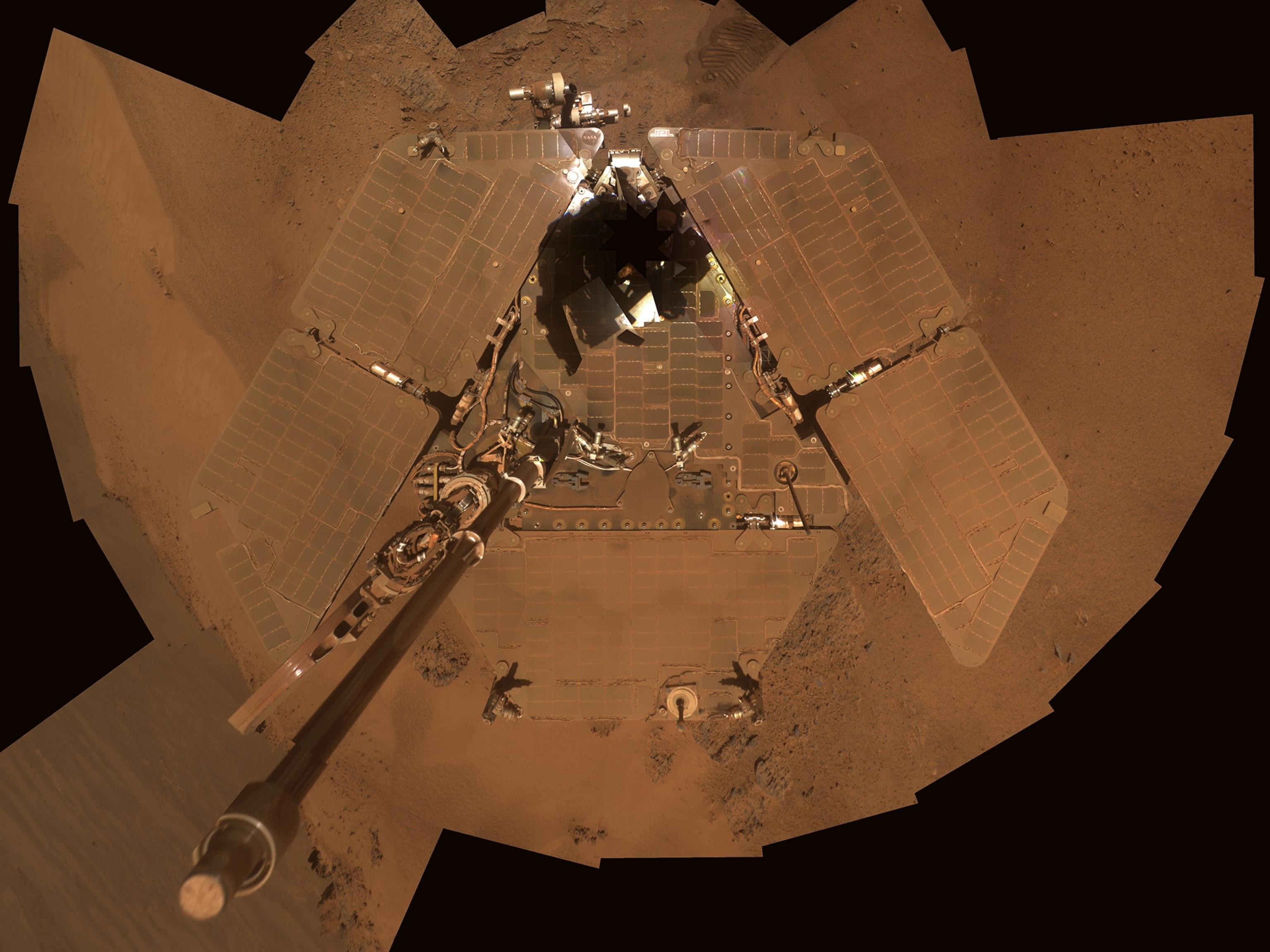

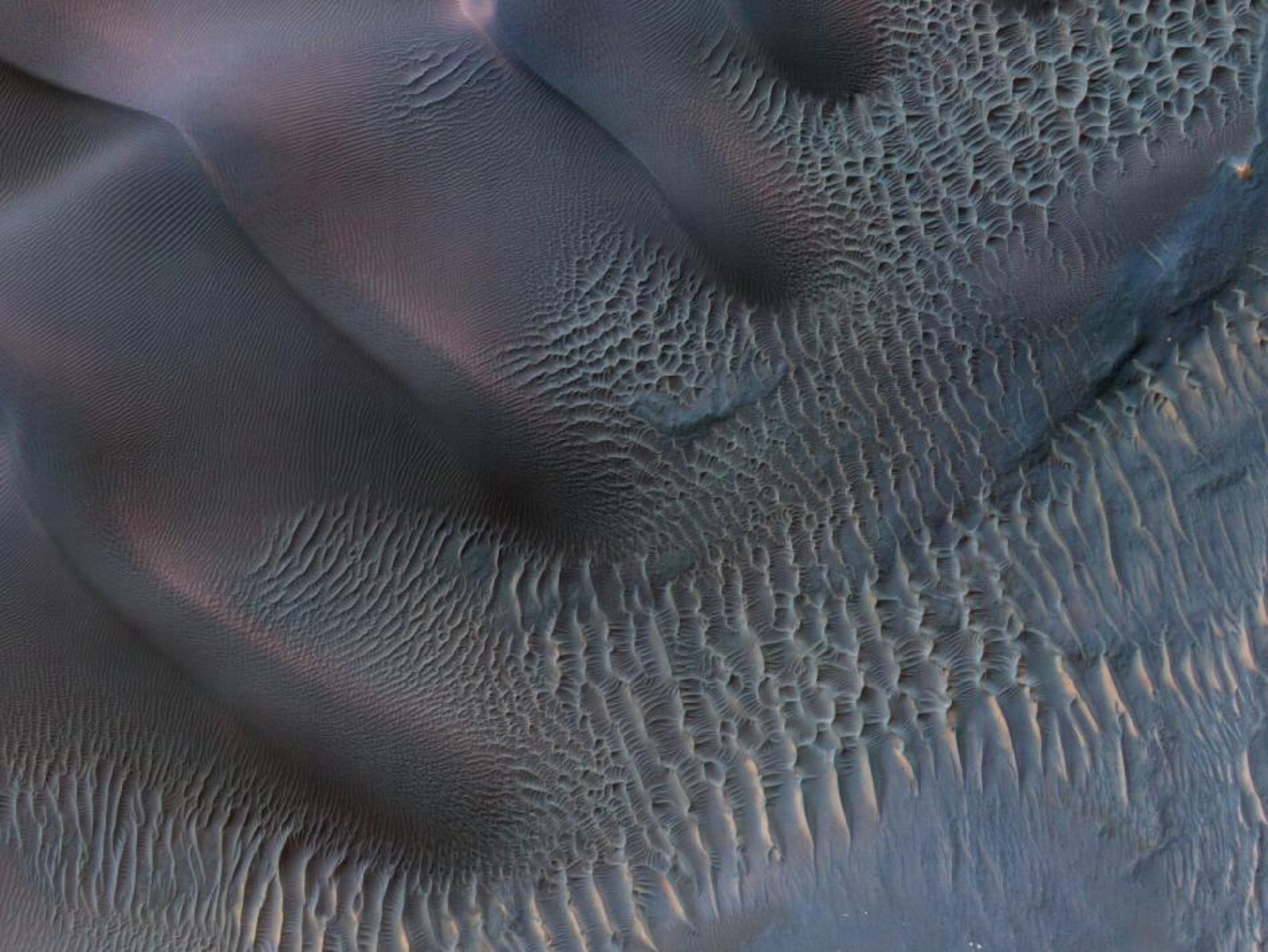

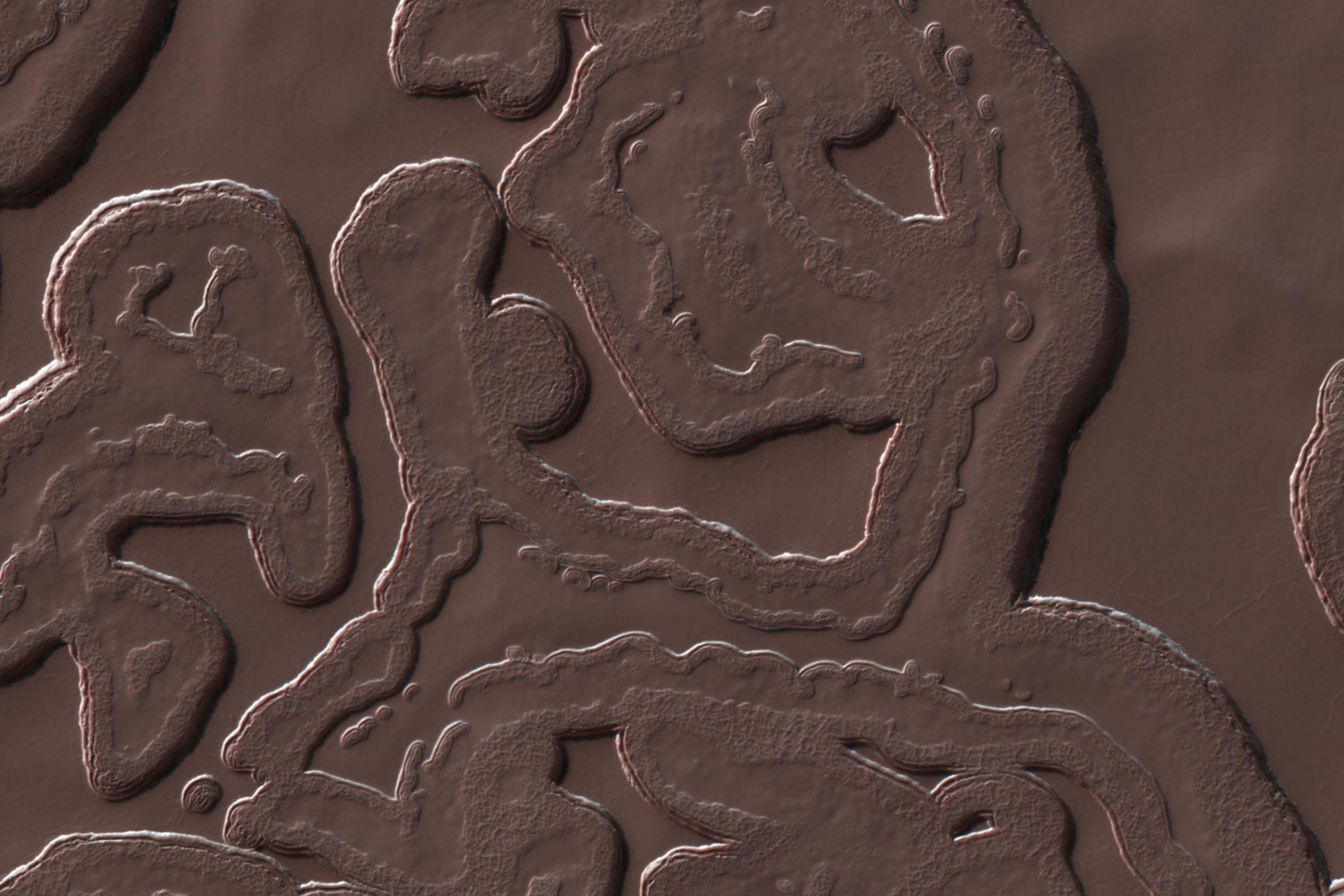

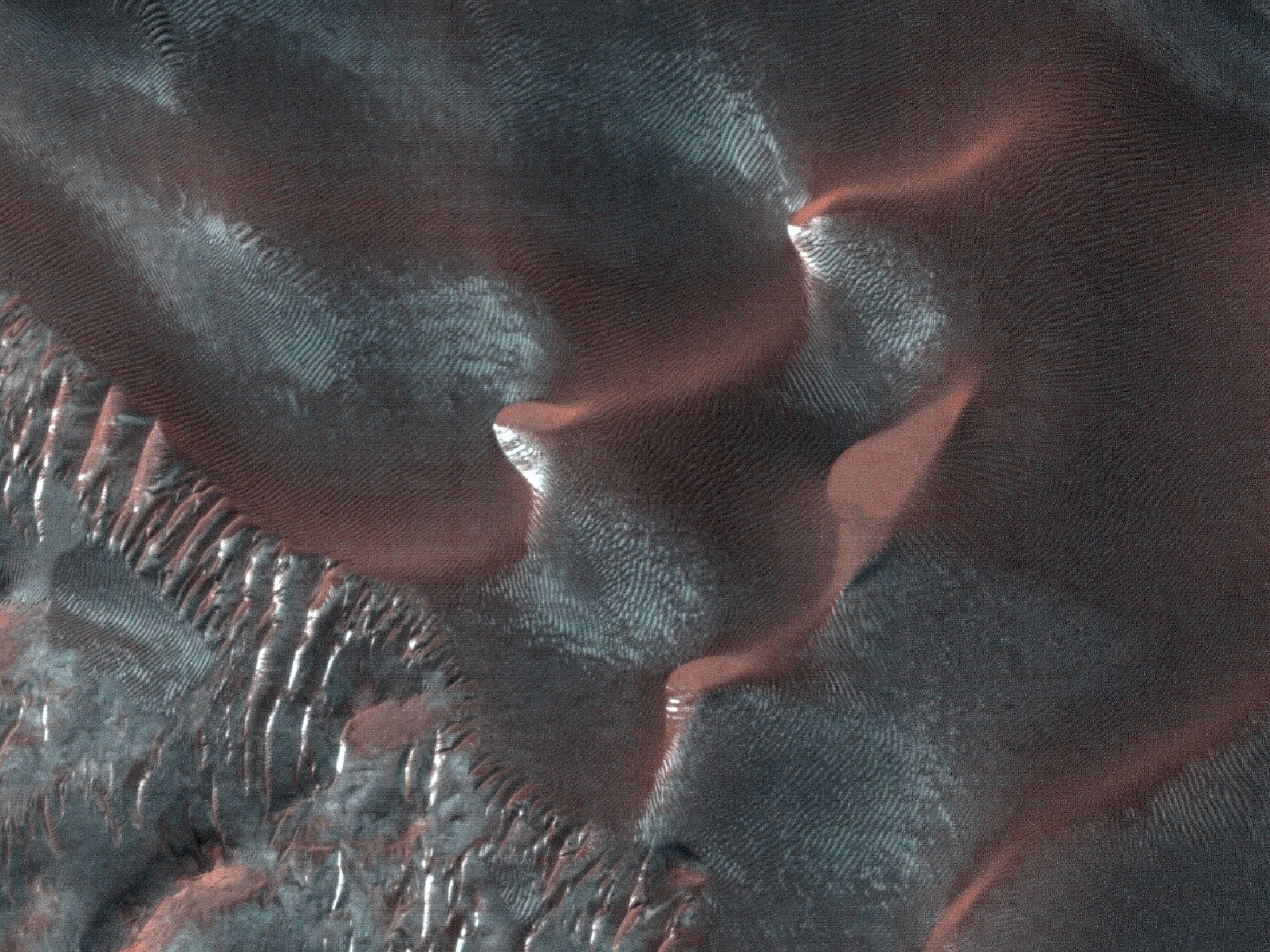

Exploring Mars in Photos

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital