The daunting challenges surrounding vaccine passports

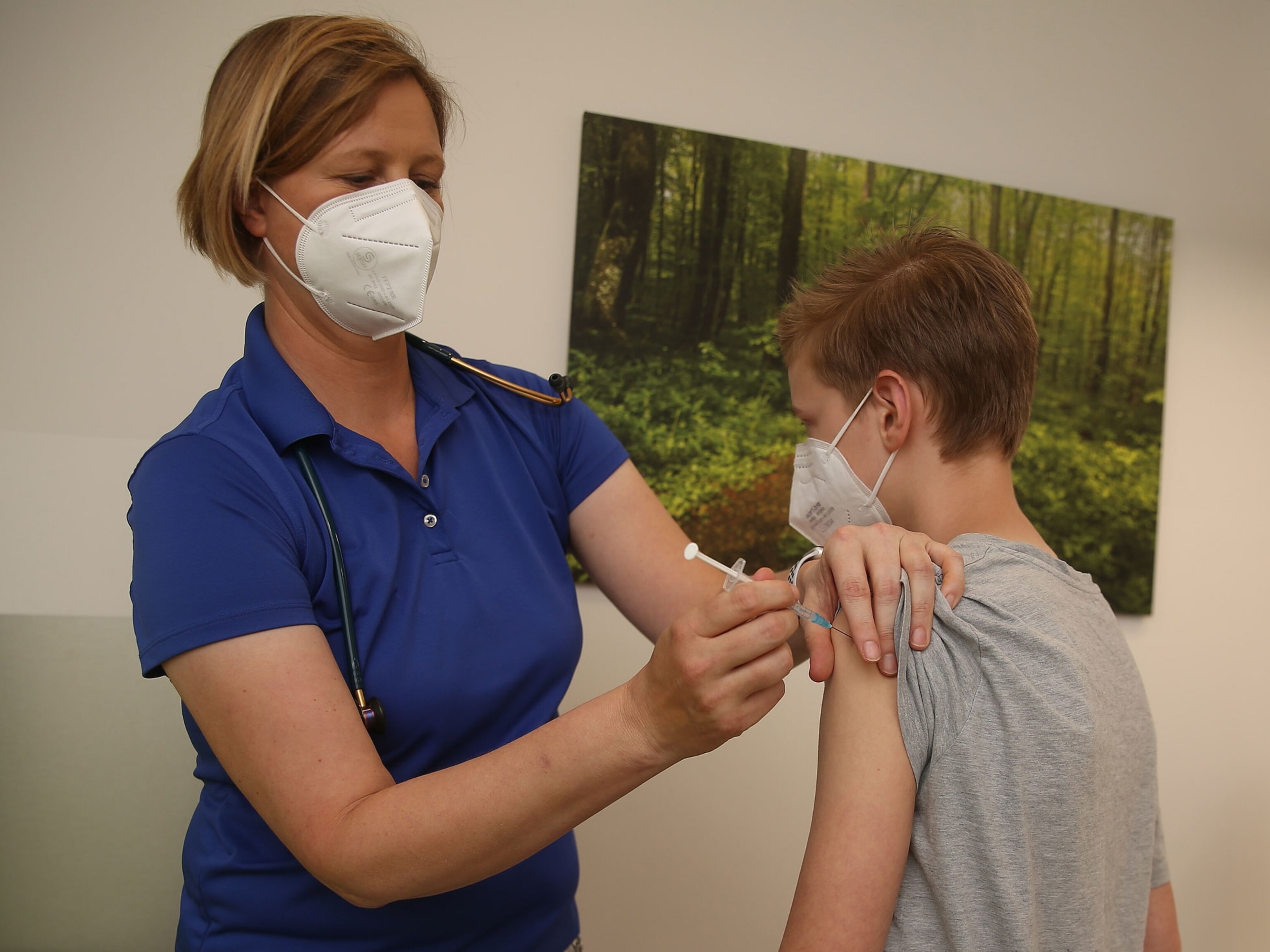

Techy apps and paper cards could prove your COVID-19 status, but they might invade your privacy.

As a documentary filmmaker, Israeli Oren Rosenfeld has captured dozens of stories about the COVID-19 pandemic over the last year. But when the time came for him to get his vaccine in Tel Aviv, he missed getting a photo of the jab.

“The nurse was pretty quick,” he says. “I didn’t want to fake the selfie, so I waited for the second shot.”

When the second dose fully kicked in, Rosenfeld was granted access to the Green Pass, Israel’s vaccine certificate program, which allows inoculated citizens to enter places such as gyms, restaurants, music venues, and movie theaters. The pass can be either physical or in a smartphone app with a code that businesses can scan. A green check will appear if the holder of the Green Pass is vaccinated and allowed to enter.

Israel’s vaccine passport is the most developed program of its kind in the world, available for the 80 percent of the adult population that is fully vaccinated. The European Union is planning to launch the similar “Digital Green Certificate” this summer that will combine information on vaccination, COVID-19 test results, and recovery from the disease into one scannable QR code that allows residents to take flights and cross the borders of member countries.

In the United States, the only way to verify your vaccination status is to flash the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) paper card that people get after their jabs. The document includes medical information such as the vaccine type, the date of the shot or shots, and where the vaccination happened (similar to the World Health Organization yellow card).

But that paper might not be enough for people eager to jet off. In March, Iceland started to welcome vaccinated visitors, but the CDC vaccination cards weren’t enough to qualify at first (the country now accepts them). With reports surfacing of fake CDC cards being sold online, getting a version that can be trusted around the globe will be essential to opening up international travel for Americans.

How to create functional vaccine passports—and how the personal data within them is stored, shared, and protected—are among the challenges that developers around the world are trying to tackle.

What is a vaccine passport?

After a more than a year of lockdowns, vaccines are promising a way to see loved ones and travel again. Countries around the world are experimenting with ways to safely—or as safely as possible—open their economies and allow people to get out of their homes and hometowns. They’re looking to do this with vaccine passports that can prove someone’s coronavirus status.

The exact form these vaccine certificates will take remains to be seen, although there are dozens of digital app options in the works. But even a simple technology of a QR code on a piece of paper might function as a passport to opening the world up again.

A digital vaccine passport is a tool that connects someone’s immunization records to an app that can be presented at border crossings or airline check-in counters. The source of the data, how it is stored, and what is shown depends on the group or business providing the tool. Many are adding paper options with barcodes or QR codes to make sure people without mobile phones can use them.

Passports in development

Multiple groups are trying to build upon paper documents by digitizing vaccination data in ways they promise will be safe, equitable, and private. The Washington Post obtained a slide deck from the Biden administration that showed at least 17 different vaccine passport initiatives being developed around the country.

The challenge is daunting. For months, many destinations have required proof of a negative COVID-19 test before visitors are allowed to enter. But securing COVID-19 test results is currently easier than proving a vaccine status. This leaves travelers sharing pieces of paper or emails from labs, sometimes in languages foreign to those inspecting the data, in order to prove that they have met the criteria to enter a country. The lack of a standard format has led to confusion.

(What does a COVID-19 vaccine mean for travelers?)

“The experience should be simple,” says Ramesh Raskar, an associate professor at MIT and founder of the PathCheck Foundation, a group of volunteers developing a vaccine passport. “It should be no more invasive and no more complicated than the CDC vaccine card.”

The PathCheck vaccine passport works by connecting certified vaccination records to a QR code that can be scanned by any facility or immigration office requiring such medical information. The data is stored in a way that can’t be tampered with and is available offline. The information can also be distributed in a paper form from the vaccine provider so that those with no or limited internet would be able to use it.

There is a clear need to standardize data across vaccine passport options so that they can be used globally and in many languages. Eric Piscini, the project lead on a vaccine passport project developed by IBM, points to how businesses can accept multiple types of credit cards (all with slightly different back end technology) using the same card reader as an example of how such standardization would work.

“You want to have a set of standards that everyone can rely on,” says Piscini. “You don’t want three different apps when you travel to three different countries.”

The IBM vaccine passport technology powers Excelsior Pass, New York state’s vaccine passport, which is currently being tested at some sports venues and arenas. New Yorkers taking part show an app with a special code that businesses can then scan with another app. That code stores information about the person’s vaccine status or a recent COVID-19 test result. A green check mark will pop up if the person is good to go (the Excelsior Pass is voluntary for now).

Another option in development is called CommonPass. It will help people prove their COVID-19 status and showcase the vital information on vaccinations no matter which standards are adopted across regions and languages, according to Paul Meyer, CEO of The Commons Project Foundation. Currently, Aruba uses it to ensure a negative COVID-19 test; Japan Airlines and Qantas airways are conducting trials of the CommonPass app.

Any vaccine passport should be designed from a public health angle and not a travel one, according to Meyer. “This is a health problem and a healthcare problem that we need to solve for,” he says. “If we do it right, then the travel world can be a beneficiary.”

Protecting privacy and fairness

With multiple digital vaccine passport options in development, the ACLU has warned that there is a possibility people’s civil liberties and privacy will be at risk. These concerns, and other political calculations, have led some states to ban the use of these passports. Florida and Texas have passed legislation making them illegal; other governors have said that they will not mandate any type of vaccine certificate to enter businesses.

Such concerns are cropping up in other countries too. Stephanie Hare, a technology researcher based in London, is deeply concerned about the British “COVID-status certification” program, which the government recently announced. The vaccine hasn’t been offered to everyone, so the program could punish those who would like it but haven’t gotten it yet. It doesn’t do anything for people gathering in private homes. Hare points to the COVID-19 tracking app that the United Kingdom released earlier in the pandemic, which failed to tell users that they had been exposed to the virus.

(Will new COVID-19 travel technology invade your privacy?)

The question of how a vaccine passport would positively affect the pandemic—including how much or how quickly it would bring down the infection rate—is where investment should be made, according to Hare.

“I would love a technology solution that solves this,” she says. “But I’m not convinced that it works. If vaccine passports aren’t going to bring down the [infection rate] number, why are we doing it? Let’s not create a fairy-tale tech solution.”

Regardless of how vaccine passports unfold in 2021, they need to be monitored and changed as we learn more about the disease, says Howard Koh, a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Koh was the assistant secretary for health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under President Barack Obama. Koh was with the department when it ended the ban on HIV-positive foreigners entering the U.S. in 2010.

That policy started in 1987, when the disease wasn’t well understood, and it survived for years due to fear and bias. Koh spoke at the first AIDS conference held in the U.S. after the ban was lifted, something he says was a major honor that shaped how he thinks about vaccine passports, which could quickly turn into something that goes from opening up the world to shutting people out.

“We need to uphold the concepts of equity and fairness and not use this as a tool that can lead to discrimination,” he says.

Nonetheless, Koh says it’s impossible to set a goal for vaccine passports without understanding how effective they turn out to be once deployed. Until then, and until more is understood about the vaccines and variants, the future of vaccine passports could remain murky.

“Exactly how the passports will play into that is unclear,” says Koh. “We have to tread carefully.”

Jackie Snow is a technology and biology writer based in Washington, D.C. Follow her on Instagram.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads