Stunning footprints push back human arrival in Americas by thousands of years

The tracks at New Mexico’s White Sands National Park are upending past assumptions on when humans first ventured into North and South America.

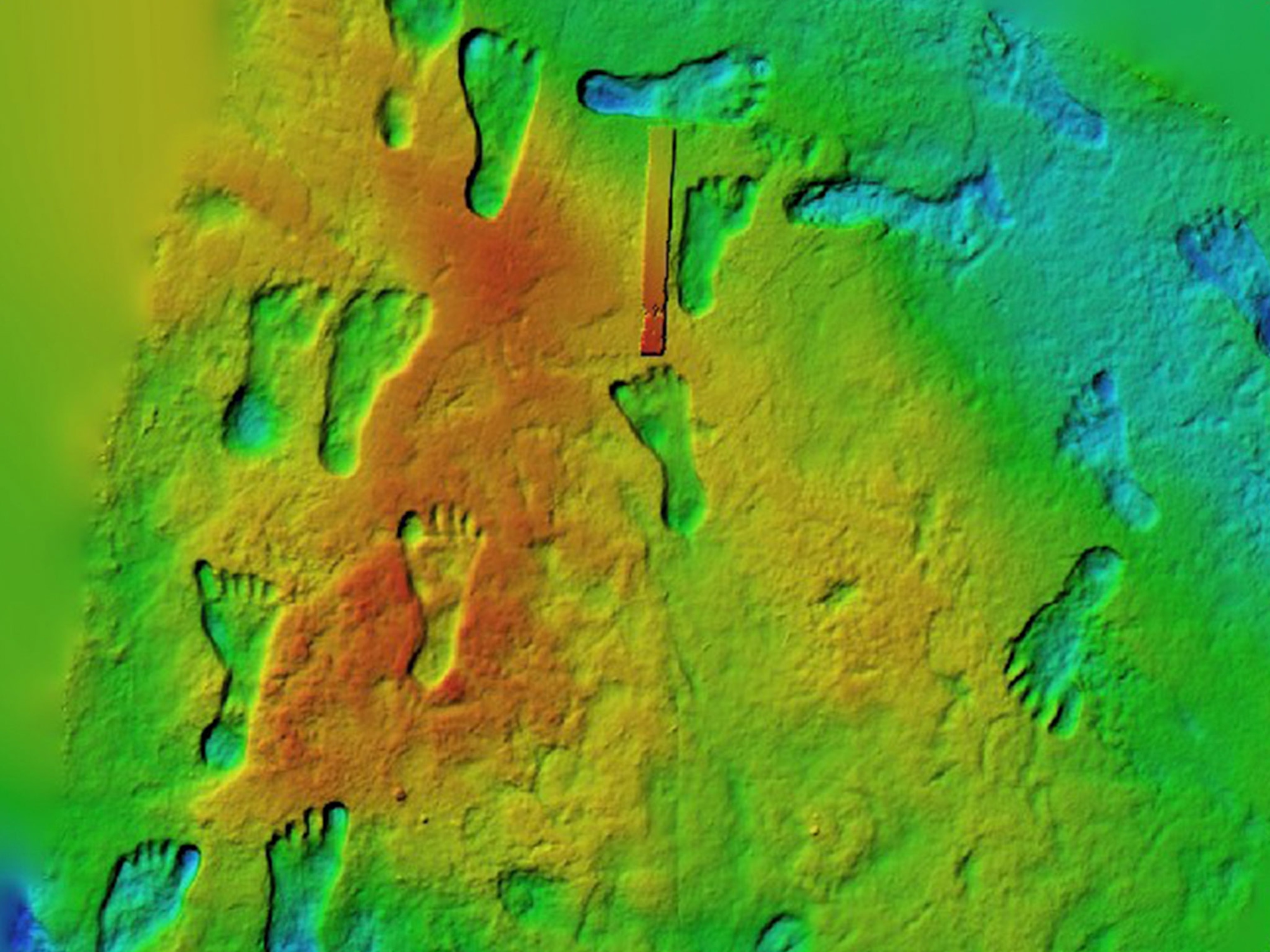

The footprints look like they were left behind just moments ago by a barefoot visitor to New Mexico's White Sands National Park, the amblings of a slightly flat-footed teen, each toe and heel impression crisply defined by a fine ridge of sand.

But this is no tourist track. These prints are among the oldest evidence of humans in the Americas, marking the latest addition to a growing body of evidence that challenges when and how people first ventured into this unexplored land.

According to a paper published today in the journal Science, the footprints were pressed into the mud near an ancient lake at White Sands between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, a time when many scientists think that massive ice sheets walled off human passage into North America.

Exactly when humans populated the Americas has been fiercely debated for nearly a century, and until recently, many scientists maintained this momentous first occurred no earlier than 13,000 years ago. A growing number of discoveries suggest people were in North and South America thousands of years before. These include the Monte Verde site in Chile that's as old as 18,500 years and the Gault site in Texas that's up to 20,000 years old. But each find kicks up a firestorm of controversy among scientists.

While the White Sands discovery doesn't close the book on these debates, it is stirring excitement.

"A discovery like this is very close to finding the Holy Grail," says Ciprian Ardelean, an archaeologist with the Autonomous University of Zacatecas. Ardelean directs excavations at Mexico’s Chiquihuite Cave, where researchers believe they have evidence for human activity in the Americas as early as 30,000 years ago.

"I feel a healthy but profound envy—a good kind of jealousy—towards the team for finding such a thing."

The footprints of ghosts—or Bigfoot?

Footprints preserved in the boundless expanses of White Sands have drawn the attention of scientists since the early 1930s, when a government trapper spotted a print measuring a stunning 22 inches long and eight inches wide. He was convinced he'd found evidence for the mythical Bigfoot.

"In a sense, he was right," says David Bustos, the park’s resource program manager and an author of the new study. "It was a big foot—but it was a big foot of a giant ground sloth and not a human.”.

Since then, careful study has uncovered thousands of tracks in the national park, providing snapshots of ancient humans and now-extinct animals like giant sloths and mammoths that wandered across the lands near ancient Lake Otero, a 1,600-square-mile body of water that dried up some 10,000 years ago. Each imprint was cast and bound millennia ago in gypsum-rich sand whose pale color gives the park its name. Some are eventually exposed by winds whipping across the dunes but quickly weather away in the elements. Other prints, hidden beneath the sand, are visible only to the trained eye as faint shifts in color at the surface at rare times when the ground is not too wet or dry.

These ephemeral appearances have earned the nickname "ghost tracks." Each footprint marks the place where an ancient relative once stood thousands of years ago.

"[It] just gives us goosebumps," Kim Charlie, a member of the Pueblo of Acoma, says of visiting the site. Many Native American tribes and pueblos feel a spiritual connection to White Sands, and Charlie is part of a committee in the Tribal Historic Preservation Office that's been collaborating with the research team to ensure the prints' preservation.

Pinning down exactly when the track-makers pressed their toes into the mud at White Sands, however, has proven challenging, says study author Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University in England. The park’s surfaces are a palimpsest of crisscrossing trackways that could have been created in separate events thousands of years apart. To securely date a print, researchers must find layers of seeds that can be dated using radiocarbon analysis, below and above layers of footprints. This way scientists can determine the earliest and latest moments in time the horizon of prints were laid down. But season after season, their search for a site with both seeds and footprints was unsuccessful.

Then came the fateful day in September 2019 when Bustos and Bennett returned to a bluff in the park they had visited more than a dozen times before. They knew the site harbored ancient seed deposits, but they hadn't yet found human footprints. On this day, however, wind had uncovered a set of unmistakably human prints that ended in a mound of sand. Scraping off the upper sandy layer revealed the ghostly outlines of a buried track.

"At that point, we said Bingo, we've got it," Bennett recalls.

A team of archaeologists, geologists, dating experts, a geophysicist, and a data scientist assembled to study the site, which spans an area roughly the size a half basketball court, with a battery of tests. Excavation revealed eight separate horizons of footprints, which contained 61 human tracks left by up to 16 people, mostly teens and children. Multiple track layers were bookended above and below by layers of sediment containing seeds from the Ruppia grass.

Radiocarbon dating of the seeds suggests humans and animals trekked across this same grassy route for at least two millennia, from 21,000 to 23,000 years ago. Bennett cautions that the date only applies to the footprints at this one location, and the dates remain unclear for the many other tracks at White Sands. But the early age of the site is a bombshell find—and the team is acutely aware of the boldness of the claim.

"We've really tried to prove it's not that old, and we keep coming up dry," says Daniel Odess, an archaeologist and Chief Scientist for Cultural Resources with the National Park Service and an author of the new study.

The wall of ice

While the latest evidence for an early human presence in the Americas comes from footprints in the desert, the bigger debate on when we arrived centers around ice. As the world entered the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), which spanned roughly 20,000 to 26,500 years ago, temperatures decreased and growing glaciers locked up an increasing volume of water, sending sea levels plummeting more than 400 feet lower than they are today. Many land features emerged from the waves, including what is now known as Beringia, a natural bridge connecting modern Siberia and Alaska that researchers believe provided a clear route for humans to make their way into the Americas.

But as temperatures during the LGM dropped, a pair of massive ice sheets—known as the Laurentide and Cordilleran—advanced across what is now Canada, forming a near-continuous icy wall from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans perhaps as early as 23,000 years ago. Many scientists have argued that humans couldn't have made inroads south into Canada until after the ice sheets retreated.

Since the mid-1900s, the threshold for these first migrations was set at 13,000 years ago, with the rise of the Clovis culture, a group known for their distinctive stone tools. Many scientists now accept that humans entered the Americas starting roughly 17,000 years ago, perhaps traveling down routes along the Pacific coast that became passable before the icy continental interior melted.

But White Sands stands among the few sites suggesting that humans were already in North America at the height of the LGM. With the discovery announced last year that suggests people may have been present in Mexico’s Chiquihuite Cave as early as 30,000 years ago, critics of the Chiquihuite study question whether humans or geology fractured the rocks.

This is a concern that has plagued many of the pre-Clovis sites, but there's no doubt the White Sands track-makers were human: "It's just screamingly obvious," says study author Vance Holliday, an archaeologist and geologist at the University of Arizona.

What's more, there isn't just one set of prints at White Sands, but multiple layers of human activity dated to earlier than 20,000 years ago. "If you don't like one layer, okay that's fine, here's another one," Bustos quips. "If you don't like that, well here's another."

Old carbon, new carbon

Some scientists still question the reliability of the dates for the footprints obtained by the research team. Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University, stresses the need for a second dating method to verify the radiocarbon results, pointing to the phenomenon of what's known as a hard water or freshwater reservoir effect that can muddy radiocarbon dates.

This happens because aquatic plants, like the Ruppia grass analyzed from White Sands, draw carbon from compounds dissolved in their wetland environment. If “old” carbon—such as carbonate rock—is present, the plants will incorporate it into their bodies, which can in turn result in deceptively old radiocarbon dates. Land plants, however, don't suffer from these effects, since they draw carbon from the atmosphere, where the relative amounts of radioactive and non-radioactive carbon are fairly constant. The team studied the potential for a freshwater reservoir effect, concluding they were likely negligible.

While the evidence the team presents can't prove such an effect is absent, it does suggest any potential impacts are fairly small, says Bente Philippsen, a radiocarbon specialist at Aarhus University who was not part of the study team. Philippsen adds that most freshwater reservoir effects are on the order of hundreds—not thousands—of years. "The most severe effect I have measured is a couple of thousand years," she says. "Even if we assume [the reservoir effect] would be as bad at the White Sands site, still it wouldn't change the conclusion that this stuff is more than 20,000 years old."

Thomas Stafford, a geochronologist with Stafford Research in Colorado who was not part of the study team, agrees on the reliability of the dates, and comments on the thoroughness of the study. "This took a long time and was really, really well done."

Additional confirmation of the dates may be tough to obtain. The team attempted to use a method involving uranium, but the samples were not well suited for the analysis, explains Jeff Pigati of the United States Geological Survey, who studied the plant remains. Davis points to other techniques, such as optically stimulated luminescence, which could help confirm the timing. But Stafford adds that OSL can have very large standard deviations, so may not provide a tidy confirmation. Yet the team is still working to perfect their methods of uranium dating and to obtain OSL dates for additional confirmation.

"I, for one, will be very excited if this is true," Davis says. But he adds, "I just think it's premature for us to get the champagne out and say it's been done, we've nailed it."

Re-thinking early humans

The reason for such a close eye on these numbers is because, if confirmed, the discovery of people in the Americas during the last glacial maximum would require a fundamental shift in scientific thinking about how people arrived in the New World. Did they sneak through inland routes before the glacial doors slammed shut during the LGM? Did they boat around icy areas of the coasts?

"More importantly, it actually requires us to think about how we do archaeology," Davis says, "because no one is looking at 22,000-year-old deposits."

In the past, Stafford says, scientists have sent him excavated material to radiocarbon date and requested he stop analyzing once he reached material 13,000 years old. Now that cutoff is closer to 18,000 years, he says, but such hard lines may have blinded past research to even older discoveries. "If you're not looking for anything, you're not going to find it," Stafford says. "So, therefore, there are very few sites."

Ardelean hopes that the White Sands work will help inspire current scientists as well as future generations of students, to take another look at early human movements through the Americas. He's dismayed at how the intense controversy has dissuaded many of his past students from continuing to study American prehistory.

But after decades of the field centering around a Clovis culture of only 13,000 years ago, change may finally be on the horizon. "I think we will not speak in terms of pre-Clovis possibilities," Ardelean says. "We will speak in terms of pre-White Sands and post-White Sands."

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico