Tulsa finally confronts the day a white mob destroyed a Black community

In 1921 rioters killed as many as 300 people, devastating a prosperous area for generations. Now the city is trying to reckon with the disgrace.

Tulsa and the Red Summer

The documentary Rise Again: Tulsa and the Red Summer, featuring DeNeen L. Brown, author of this article, will air in June on National Geographic.

Hear more about a reckoning in Tulsa in our podcast, Overheard at National Geographic.

On June 1, 1921, as a white mob descended on Greenwood, the all-Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Mary E. Jones Parrish grabbed her young daughter’s hand and ran for her life. Dodging machine-gun fire, they sprinted down Greenwood Avenue, a street so prosperous it would later be remembered as Black Wall Street. Above them, the sky buzzed with several civilian airplanes dropping makeshift turpentine bombs. Thousands of Black people fled while the mob advanced—looting; torching houses, churches, and other buildings; and shooting Black people in cold blood. “Get out of the street with that child, or you both will be killed!” someone yelled. But Parrish saw nowhere to hide. She felt it would be “suicide” to remain in her apartment building, “for it would surely be destroyed and death in the street was preferred, for we expected to be shot down at any moment,” she recalled in Events of the Tulsa Disaster, her 1922 book, which includes rare witness accounts of what has become known as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Black people rushed out of burning buildings, Parrish wrote, “some with babes in their arms and leading crying and excited children by the hand; others, old and feeble, all fleeing for safety.”

Parrish hurried toward Standpipe Hill, the highest ground in Greenwood. But she found no safety. As she looked below, she saw an exodus of Black Tulsans and smoke rising from what had been a bustling commercial district. Someone in a truck called out to her. She and her daughter scrambled aboard, escaping from the death and destruction.

By the end of the two-day rampage, as many as 300 Black citizens had been murdered and Greenwood had been destroyed.

The attack was one of the worst acts of terrorism in U.S. history—part of a World War I–era wave of racial violence by white people against Black communities. Some historians describe what happened in Greenwood as “a massacre, a pogrom, or, to use a more modern term, an ethnic cleansing,” reported the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Commission, the first governmental investigation into the bloody assault, 80 years later—a gap that reflects how white Tulsa essentially excused and covered up the massacre for generations.

“For others, it was nothing short of a race war,” the commission continued. “But whatever term is used, one thing is certain: When it was all over, Tulsa’s African American district had been turned into a scorched wasteland of vacant lots, crumbling storefronts, burned churches, and blackened, leafless trees.”

(See how the 1921 Tulsa Massacre robbed a black community of generational wealth.)

Nearly 10,000 people—almost the entire Black population and close to a tenth of Tulsa’s total—were left homeless. Some of Greenwood’s leading citizens, including A.J. Smitherman, the crusading publisher of the Tulsa Star, and wealthy hotel owner J.B. Stradford, left town after being falsely accused of instigating the riot.

“In addition to the material items, we lost people. We lost generations, not just generational wealth. We lost bodies,” says Oklahoma State Representative Regina Goodwin, whose grandfather and great-grandparents survived the massacre. “Dreams were unfulfilled, and the sadder truth, some dreams were never dreamt,” she adds. “Think of the classic poem by Langston Hughes, ‘What happens to a dream deferred?’ ”

Today, as generations descending from Tulsa’s Black families of the early 20th century remain scattered, Greenwood’s business district has been reduced to one gentrified block catering mostly to white people. But the city finally is trying to reckon with the Tulsa Race Massacre, a disgrace it has long tried to forget. A search for mass graves of victims continues, after scientists found one last October in the Black section of one of the city’s public cemeteries.

At the time of the massacre, Greenwood was a vibrant Black community in a nation where racial segregation—and limited economic opportunities for African Americans—was a theme of daily life.

The 1905 discovery of the Glenn Pool Oil Reserve catapulted Tulsa, conveniently located at a railroad and river crossroads, into an oil boom. People flooded into the region for jobs. Black people left places such as Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas for Greenwood, which some called the promised land, a glorious mecca rich with opportunities and the chance to build a Black community that flourished on its own terms.

(Before the Tulsa Race Massacre, Black business was booming in Greenwood)

In 1908 O.W. Gurley erected one of the first buildings in Greenwood, a rooming house on a “muddy trail,” as the riot commission report described it, that would become Greenwood Avenue. He later “bought 30 or 40 acres, plotted them and had them sold to ‘Negroes only.’ ”

Greenwood was impressive. Redbrick buildings lining the main street contained “two theaters, groceries, confectionaries, restaurants, and billiard halls,” writes Scott Ellsworth in Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

“A number of black Tulsa’s eleven rooming houses and four hotels were located here.” Doctors, lawyers, insurance agents, printers, bankers, and other Black entrepreneurs opened businesses in Greenwood. Parrish described some of the houses as “homes of beauty and splendor,” although most residents lived quite modestly.

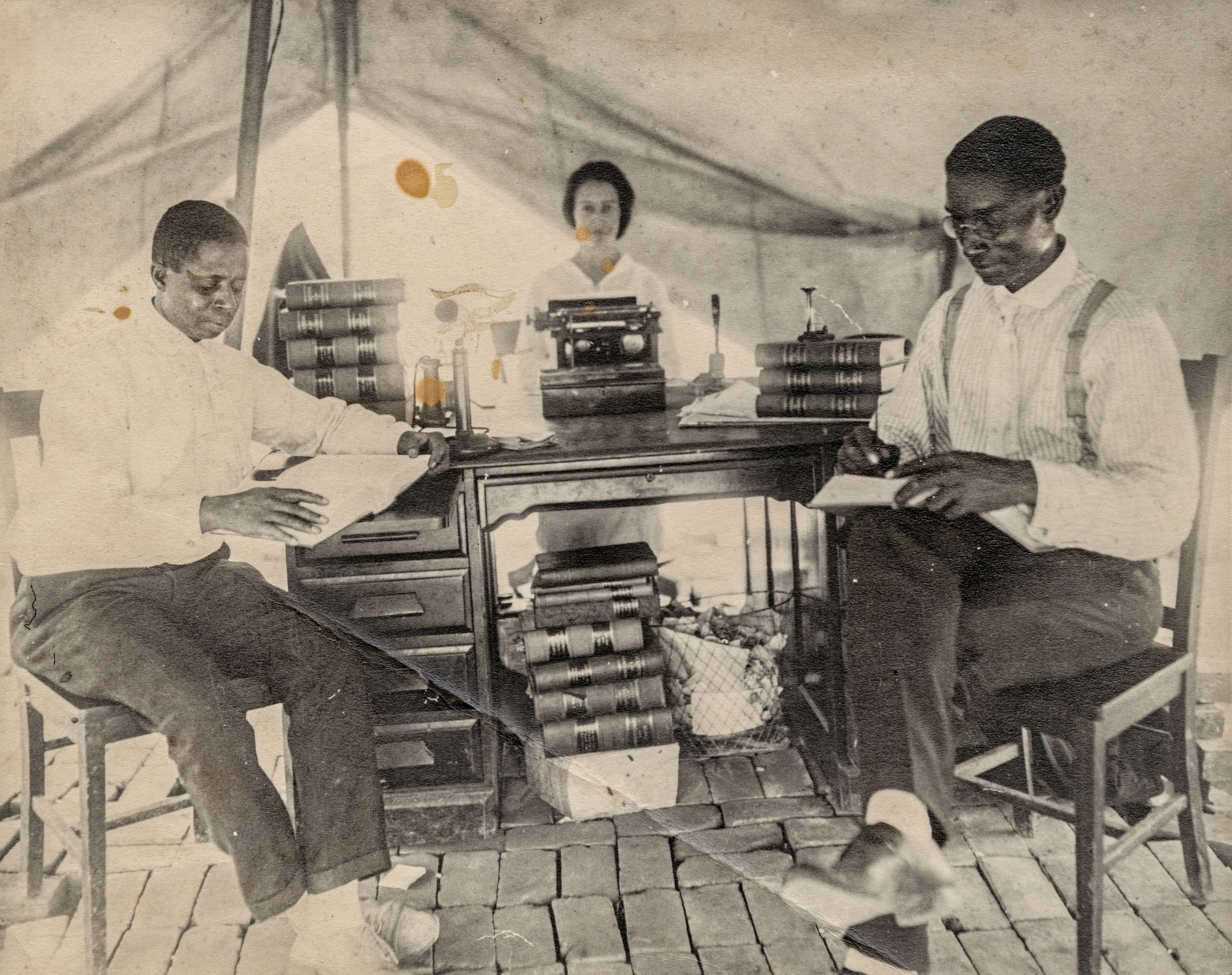

By 1921, Greenwood, racially segregated from white Tulsa by Jim Crow laws, was a self-contained world. It had nationally recognized schools, including Dunbar Elementary School and Booker T. Washington High School; two Black newspapers, the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun; a Black-owned hospital; and more than a dozen Black churches.

“After spending years of struggling and sacrifice, people had begun to look upon Tulsa as the Negro Metropolis of the Southwest,” Parrish wrote. “Then the devastating Tulsa Disaster burst upon us, blowing to atoms ideas and ideals no less than mere material evidence of our civilization.”

The massacre came on the heels of the Red Summer, a reign of terror in 1919, when white mobs killed and lynched hundreds of Black people in more than 25 places across the country. The term—coined by James Weldon Johnson, who wrote the words set to music in “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often called the Black national anthem—evoked the blood spilled in the streets of Washington, D.C.; Elaine, Arkansas; Knoxville, Tennessee; Omaha, Nebraska; Charleston, South Carolina; Longview, Texas; and Chicago, Illinois.

Thriving districts such as Greenwood threatened the racial hierarchy that had dominated American life for much of the nation’s first 145 years, as did the Black soldiers who had returned from World War I demanding the same human rights they’d fought for abroad. The Ku Klux Klan, reborn in 1915 with a surging membership, responded with a wave of racial violence. Black people fled the South for cities in the West and North—where what historian Scott Ellsworth describes as “new and especially insidious forms of militant white racist thought” also held sway.

“In these years I have noticed a growing racial hate by the lower Whites because of Negro prosperity and independence,” Tulsa survivor E.A. Loupe told Parrish. These forces “broke loose on a pretense, and thus swept down upon the good citizen with all the hate and revenge that has been smoldering for years.”

(Our honest, revealing, and hidden thoughts on race—in 6 words)

The Tulsa massacre began as many of the Red Summer rampages did, with an accusation that a Black man had assaulted a white woman. In this case the roles were filled by teenagers. On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, 19, entered the elevator in the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. As he went from the first floor to the third, he may have bumped into or stepped on the foot of the elevator operator, a 17-year-old named Sarah Page. She shrieked, someone came to see what had happened, and Rowland ran.

Rumors of the incident swept through Tulsa’s white community, becoming “more exaggerated with each telling,” according to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum.

The next day, a headline in the Tulsa Tribune blared, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.” Page claimed Rowland had “attacked her, scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes,” the newspaper reported.

Rowland was arrested and held at the Tulsa County Courthouse. Soon a lynch mob surrounded the courthouse, blocking streets and spilling over into the front yards of nearby homes. A group of armed Black men, many of them war veterans, hurried from Greenwood to the courthouse to protect Rowland. The previous year a white man had been lynched in Tulsa—the city’s first—and they saw how easily it played out. They intended to prevent another one.

The sheriff rejected their help but managed to prevent Rowland from being lynched. (The charges against Rowland would be dropped later.) But the crowd’s attention had shifted. A white man confronted an armed Black veteran. A shot was fired, and all hell broke loose.

That night, hundreds of white people, many of them deputized by city officials, marched on Greenwood.

They were merciless. Some white men broke into the home of an elderly Black couple. “The old man, 80 years old, was paralyzed and sat in a chair,” said an account published 10 days later in a Chicago newspaper. “They told him to march and he told them he was crippled, but he’d go if someone would take him, and they told his wife to go, but she didn’t want to leave him. He told her to go anyway. As she left, one of the damn dogs shot the old man, then they fired the house.”

George Monroe, who was five years old then, recalled hiding with his older sisters and a brother under their parents’ bed. “When we saw … four men with torches in their hands—these torches were burning—when my mother saw them coming, she says, ‘You get up under the bed, get up under the bed!’ And all four of us got up under the bed,” Monroe told the riot commission eight decades later.

“I was the last one and my sister grabbed me and pulled me under there,” said Monroe, who watched the men ransack the room and set the curtains on fire. “While I was under the bed, one of the guys coming past the bed stepped on my finger, and as I was about to scream, my sister put her hand over my mouth so I couldn’t be heard.”

The mob’s brutality was evident throughout Greenwood. “I was downtown with a friend when they killed that good, old colored man that was blind,” a massacre survivor told the commission. “He had amputated legs. His body was attached at the hips to a small wooden platform with wheels. One leg stub was longer than the other, and hung slightly over the edge of the platform, dragging along the street. He scooted his body around by shoving and pushing with his hands covered with baseball catcher mitts. He supported himself by selling pencils to passersby, or accepting their donations for his singing of songs.”

(This is how we can envison Black freedom)

The mob tied a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets of Greenwood behind an automobile.

A.C. Jackson, who’d been called “the most able Negro surgeon in America” by one of the founders of the Mayo Clinic, tried to head off the mob. When a group of white rioters gathered on his front lawn, he came out of his house with his hands up, saying, “Here I am, boys. Don’t shoot.” They shot the distinguished doctor anyway, and Jackson bled to death. Frissell Memorial Hospital, the only hospital serving Black people, had been burned to the ground.

White men wearing uniforms “carried cans of oil into Little Africa,” a name white people used for Greenwood, “and after looting the homes, set fire to them,” wrote Walter White, an investigator for the NAACP, who traveled to Tulsa shortly after the massacre. White, a Black man whose light complexion allowed him to pass as white as he interviewed witnesses to lynchings and killings across the nation, was shocked by what he learned in Tulsa. “Many are the stories of horror told to me—not by colored people—but by white residents,” White wrote in a report published in the Nation magazine in 1921.

Tulsa likely became the first U.S. city bombed by air, as some local white pilots took to the sky armed with incendiary devices. “From my office window, I could see planes circling,” wrote lawyer B.C. Franklin in a typed witness manuscript. “Down East Archer [Street], I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from the top. ‘What, an attack from the air too?’ I asked.”

Then he saw three men running on Greenwood Avenue. “The three men—one of whom lugged a heavy trunk on his shoulder—were all killed as they were crossing the street—killed before my very eyes.”

As night closed in on the horrors of May 31, some Black people huddled, praying the worst of the violence was over. But the worst was to come.

“Tuesday night, May 31, was the riot,” a witness later told Mary Parrish. “Wednesday morning, by daybreak, was the invasion.”

The mob had retreated only to regain strength. As many as 10,000 white people amassed on the outskirts of Greenwood. A machine gun was mounted on top of a grain elevator.

At exactly 5:08 that morning, a piercing whistle sliced the morning silence. “With wild, frenzied shouts,” a witness later recalled, “men began pouring from behind the freight depot and the long string of boxcars and evidently from behind the piles of oil well [piping].”

The white rioters set fires “house by house, block by block” as they moved through Greenwood. They burned “a dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drug stores, eight doctor’s offices, more than two dozen grocery stores, and the Black public library. More than a thousand homes were torched, the fires becoming so hot that nearby trees and outbuildings also burst into flame.” The mob prevented city firefighters from quenching the fires.

Millions of dollars of Black wealth vanished that day. Gurley, one of the community’s founders, lost as much as $157,783, according to the Tulsa Race Riot Commission report. Today the value of his destroyed assets (compounded annually at 6 percent interest) would have grown to $53.5 million—a potential fortune lost.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the city smelled of death.

The governor called in out-of-town National Guard units to keep the peace. The local units had joined the mob’s destruction. Rather than protecting Greenwood residents, they’d detained them in internment camps at the city’s convention hall, baseball park, and fairgrounds. Black Tulsans were kept under armed guard, “not able to leave without permission of white employers,” according to a 2020 Human Rights Watch report on the massacre. “When they did leave, they were required to wear green identification tags.”

While they were detained, mobs looted their homes—stealing furs, pianos, music players, furniture, clothing—and disposed of the victims’ bodies. Survivors recounted seeing bodies of Black people dumped into mass graves, thrown on trucks, or tossed into the Arkansas River. “I saw two truckloads of bodies,” one survivor told the riot commission. “They were Negroes with their legs and arms sticking out through the slats. On the very top was a little boy just about my age. He looked like he had been scared to death.”

You May Also Like

Social media star Alexis Nikole Nelson is teaching a new generation about foraging

No white person was ever arrested in connection with the massacre.

For nearly 80 years, the city of Tulsa was haunted by silence over what had happened. Black survivors who’d returned to rebuild kept quiet about the massacre. City leaders, calling the rampage an embarrassment, covered it up. At the University of Tulsa archives, someone used a razor to excise stories about it from magazines. The Tulsa Tribune article claiming that Rowland had assaulted Page was torn out of the newspaper, as was the editorial “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

Yet the story of the massacre could not be erased, says Goodwin, the Oklahoma state representative. “The souls remain and we honor them, but these were generations that could have been born, and we don’t have them. Those folks were killed, murdered, burned, and shot; those were people. We lost daddies, mamas, and babies. They were murdered, and it was arson, and no one was ever charged. No one was ever convicted, and no one was ever held accountable. And we will not forget.”

In 1997, 76 years after the massacre, Oklahoma opened an investigation into what happened. Don Ross, a state legislator whose grandfather had survived the violence, authored a bill that created the Tulsa Race Riot Commission in response to a local reporter who had called the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, which killed 168 people, the worst civil unrest since the Civil War.

“My father stated to the reporter, ‘No, the worst to occur was just an hour away from the State Capitol, in Greenwood,’ ” J. Kavin Ross, the son of Don Ross, told me. “That is what started the story.”

J. Kavin Ross, a journalist in Tulsa, worked with the commission, interviewing and videotaping more than 75 survivors. It was haunting “to hear the stories from them, from a child’s perspective. Many were five, nine, 10, and some were teenagers at the time,” he said. “It was something locked in their psyche all this time. They’d say, ‘I remember something else. Come back and interview me again.’ ”

In 1998 a team led by Scott Ellsworth, whose new book The Ground Breaking: An American City and Its Search for Justice recounts the cover-up and investigation of the massacre, identified three locations where there might be mass graves: Newblock Park (a dump in 1921), Booker T. Washington Cemetery, and Oaklawn Cemetery. Underground anomalies discovered with ground-penetrating radar at Newblock Park were discounted upon further investigation, but eyewitness testimony from Clyde Eddy, a white Tulsan, expanded the search at Oaklawn.

“A cousin of mine, we passed down by the old Oaklawn Cemetery,” Eddy told the commission in 1999. “We saw a bunch of men working, digging a pit, and we saw a bunch of wooden crates lying around. We went and took a look. We walked up to the first crate, and there were bodies of three Blacks. The next crate, it was much larger, and there were at least four bodies in it.”

A team examined the Eddy site with ground-penetrating radar, electromagnetic induction, and a magnetometer and discovered an anomaly bearing “all the characteristics of a dug pit or trench with vertical walls and an undefined object within the approximate center.” Yet the area had been reserved for white burials in 1921.

The commission decided not to authorize a physical search, and Susan Savage, Tulsa’s mayor at the time, closed the investigation before scientists could dig, saying she did not want to disturb nearby burials.

The search seemed over. But in 2018 I wrote a front-page story in the Washington Post that questioned the ending of the investigation. I had traveled to Tulsa to visit my father and noticed that development was gentrifying Greenwood—a place that survivors’ descendants consider to be the sacred ground of the massacre. A few days after the story was published, the city’s mayor, G.T. Bynum, announced that he would reopen the investigation and search for mass graves.

“If there are mass graves in Tulsa, we should find them,” Bynum told me. “If you get murdered in Tulsa, we have a contract with you that we will do everything we can to find out what happened and render justice. That’s why we are treating this as a homicide investigation for Tulsans who we believe were murdered in 1921.”

Bynum, a white Republican, acknowledged that the city had covered up the massacre for nearly a century, but as mayor, he promised to follow the truth. “It’s more important for me to be on the right side of history,” he said.

Even so, today he’s facing pressure from all sides. Some white people have confronted him, saying he should leave the past buried. Black residents descended from survivors, meanwhile, continue to demand a thorough search for mass graves as well as reparations for the wealth that was destroyed.

In 2019 the city formed a committee of descendants, researchers, and community activists. At their request, a group of experts, including archaeologists, historians, and forensic anthropologists, used ground-penetrating radar to look for evidence of anomalies at the 1999 sites.

Led by the Oklahoma Archeological Survey based at the University of Oklahoma, the team searched Oaklawn Cemetery and Newblock Park while the city negotiated for access to a third site, the privately owned Rolling Oaks Memorial Gardens, formerly Booker T. Washington Cemetery. On December 16, 2019, the scientists announced they had found anomalies beneath the ground at Oaklawn and in an area of Tulsa called the Canes, now a homeless encampment, near where the I-244 freeway crosses the Arkansas River.

Oaklawn Cemetery, Tulsa’s oldest existing public burial ground, is just blocks from Greenwood. At the entrance, a map still shows the dividing line between the “white” and “colored” sections.

In July 2020 the scientists broke ground in a “colored” section called the Sexton Area, a plot marked by pink crape myrtle trees. After eight days of digging, the scientists hadn’t found a mass grave. The city decided to expand the search.

Three months later, on October 19, 2020, a second excavation began, concentrating on an area that researchers called the “Original 18” site, where officials suspected 18 Black people had been buried in 1921.

Two days later, scientists located the remains of a trench under a tree near the tombstones of Reuben Everett and Eddie Lockard, the only marked graves of known massacre victims in the cemetery. The pit contained at least 11 coffins.

White rioters set fires, house by house. They burned churches, hotels, grocery stores, the Black public library. The mob prevented city firefighters from quenching the fires.

“This constitutes a mass grave,” state archaeologist Kary Stackelbeck told reporters at a news conference in Tulsa. But she said more research is needed to determine whether the bodies belonged to victims of the massacre.

Signs of trauma, gunshot wounds, or burns could connect the bones to the massacre, says Phoebe Stubblefield, the forensic anthropologist who would examine the remains. But Stubblefield, whose ancestors survived the violence, says that before she can do that, the city must obtain permission from a judge to exhume the remains. The burial site may contain many more coffins stacked on top of each other.

“We could be looking at more than 30 individuals interred in this mass grave,” Stackelbeck says. Steps had been cut into the hard soil, she says, “presumably to get in and out of the grave shaft.”

It’s unlikely the gravediggers would have gone to that trouble to bury only a few people.

Each Wednesday before Bible study, the Reverend Robert Turner, pastor of Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church—one of the last original structures in Greenwood—walks to City Hall to protest the massacre and demand reparations.

“Black people were murdered in this city, killed by mass racial terror,” he shouts. “Innocent lives were taken. Babies burned. Women burned. Mothers burned. Grandmothers burned. Grandfathers burned. Husbands burned. Houses burned. Schools burned. Hospitals burned. Our sanctuary burned. The blood of those killed in Tulsa still cries out.”

But when news of the discovery reached him, Turner sank quietly to his knees at the cemetery’s wrought-iron fence and prayed.

Kristi Williams went to the cemetery too. The mass grave had been discovered where she and other Black activists had staged a “die-in” in 2019 to bring attention to the search for massacre victims.

She and a dozen others had lain down on the grass near the two marked tombstones of known riot victims. Suddenly, two of the protesters—J. Kavin Ross and Tiffany Crutcher, a community organizer—leaped up.

“They felt something pull on them from the ground,” Williams told me. “We thought they were being silly. But when we got the news they found a mass grave, it came full circle to me. Our ancestors have been crying out, and that’s where they were.”

At the cemetery’s border, Williams poured a water libation and prayed: “Ancestors, thank you for crying out to us. It is my prayer that we connect you all with your families and that you guide us through this process for justice. I’m so sorry this happened to you.”

This story appears in the June 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

DeNeen L. Brown, a native of Oklahoma, has written extensively about the race massacre. Bethany Mollenkof chronicled her pandemic-era pregnancy for National Geographic.