European ‘shamans’ took psychedelic drugs 3,000 years ago

Archaeologists usually rely on indirect information from pots and jars to understand our millennia-old taste for mind-altering substances. Now, hair from a Spanish cave provides the first direct evidence for human consumption on the continent.

In 1995, explorers made a remarkable discovery in a gorge on the Mediterranean island of Menorca: a cave with more than 200 intact burials dating from roughly 1,600 to 800 B.C., many related across multiple generations. Among the unusual finds near some burials in the cave, known as Es Càrritx, were hollow, sealed tubes made of wood or antler that contained strands of hair from the deceased, cut and dyed or colored with red pigment.

But then researchers came across a “hidden” collection of ten more hair-containing tubes secreted far from the burials in the cave. And now, 28 years later, those ancient strands of hair are affirming what archaeologists have long suspected: people across the planet have been taking hallucinogenic drugs for thousands of years.

In a study published today in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers confirm that chemical signatures in the secreted samples of Es Càrritx hair provide the first direct evidence for hallucinogenic drug use in Europe some 3,000 years ago.

Previous studies have only found indirect evidence for the ingestion of mind-altering substances on the continent, in the form of tell-tale chemical traces in residue from ancient containers or as psychoactive plant remains left at ritual sites.

The findings are an affirmation of the knowledge and use of plants as drugs among prehistoric Europeans, says ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini, an expert on psychoactive substances who was not involved in the research.

Connecting to the spirit world

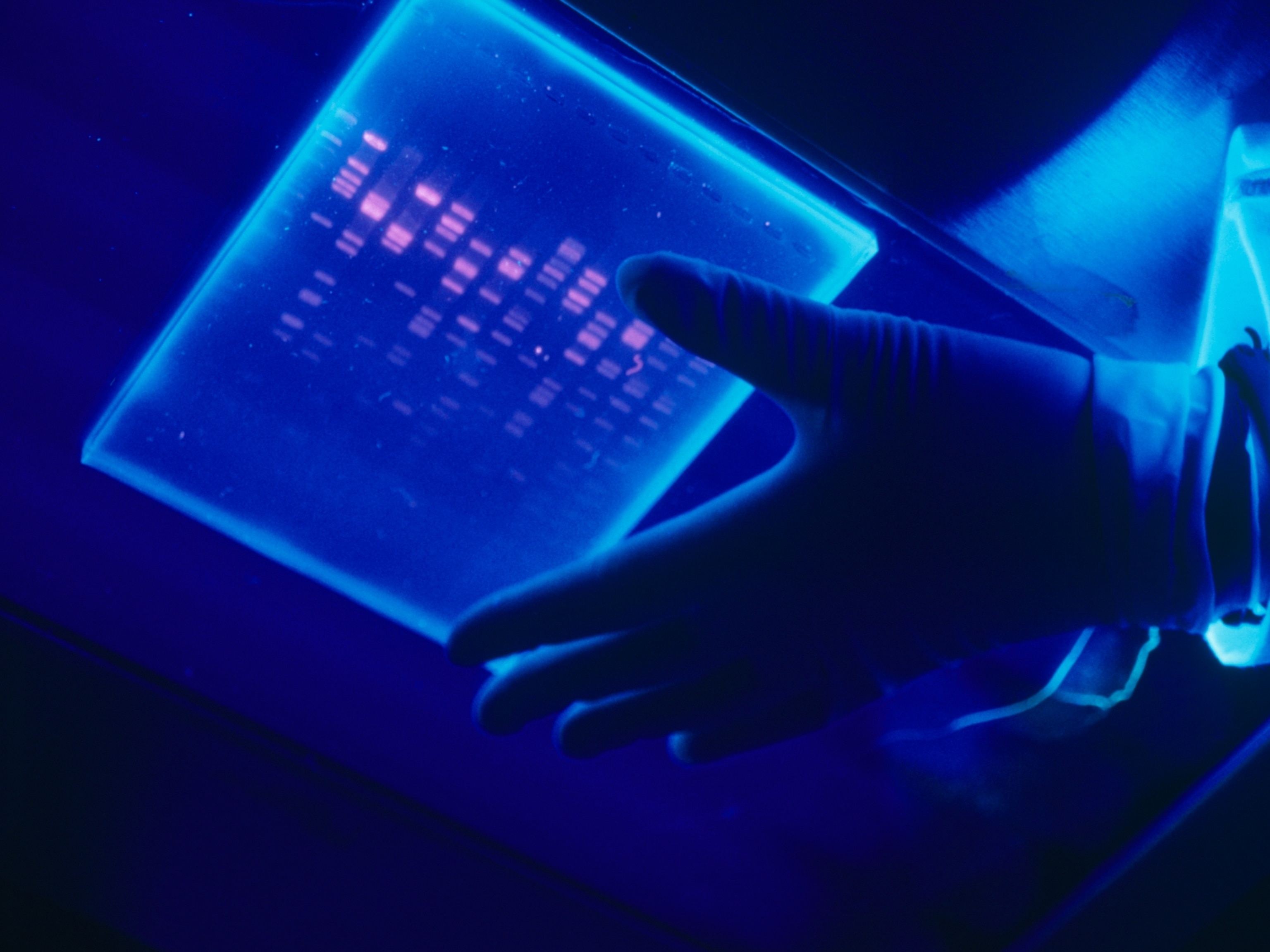

In the latest study, led by prehistorian Elisa Guerra Doce of Spain’s University of Valladolid, the strands of “ritually buried” hair from Es Càrritx were analyzed with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry, which revealed the presence of the alkaloids atropine, scopolamine, and ephedrine. The study authors suggest the atropine and scopolamine came from the consumption of plants from the nightshade family, such as mandrake (Mandragora autumnalis), henbane (Hyoscyamus albus) and thorn apple (Datura stramonium); while the ephedrine probably came from the consumption of joint pine (Ephedra fragilis.)

Atropine and scopolamine are hallucinogenic and can induce delirium and altered sensory perception. The study authors propose they were taken deliberately during “shamanic” rituals, supposedly to connect a community with what was seen as the spirit world.

Atropine is especially powerful. “Atropine alkaloids could induce hallucinations, such as the sensation of flying or out-of-body experiences,” Guerra Doce tells National Geographic.

Ephedrine, on the other hand, is not hallucinogenic but a stimulant, and a common medicine for breathing problems. It’s impossible to determine whether the ephedrine was consumed alongside the hallucinogens, perhaps to help control the physical effects of the experience, or if the ephedrine was consumed separately as a medicine.

The researchers were stunned by the level of preservation they found in the ten “hidden” hair samples, which date from the last 300 years of activity at Es Càrritx until 800 B.C., when burials at the cave stopped. There’s some evidence of similar ceremonies at other caves on Menorca, and the unusual hair rituals may have been taking place during a time of cultural change on the island as a way to preserve local tradition while relationships with neighboring islands and distant foreign powers ebbed and flowed. Archaeologists have seen nothing like it anywhere else: “We are very, very lucky,” Guerra Doce says.

'Maybe we’ll never be able to explain it.'

For archaeologist and analytical chemist Rebecca Stacey of the British Museum in London, the evidence from Menorca solidifies the idea that psychoactive drugs were being actively consumed in Europe’s prehistory.

Stacey wasn’t involved in the latest study, but her own research in 2018 found opium alkaloids in the residue of 3,600 year-old jugs from Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean. While this could be early indirect evidence for drug use, it’s also possible the poppy oil in the jugs was a perfume ingredient, she says. But taken with the new evidence for drug ingestion from Menorca, she says, “we are able to take a step closer to the past human experience of the substances and their properties.”

Samorini, who lives on the nearby island of Majorca, suggests that the ephedrine found in the hair strands show it was widely used, perhaps when building the many megalithic monuments that now cover Menorca. “Ephedrine could have been useful to move these very big stones,” he notes.

Samorini adds that he’s never heard of anything like the funeral ritual for the hair of the supposed "shamans" from Menorca. “This is very strange,” he says. “Maybe we’ll never be able to explain it.”

Direct and indirect evidence for ancient hallucinogenic drug use has been found on almost every continent; the oldest direct evidence, from Asia, likely dates to 4,600 years ago. The earliest indirect evidence for psychoactive drug use in Europe stretches back to the Neolithic period about 6,000 years ago, but much of it is heavily disputed.

Guerra Doce says it’s likely even older proof of human hallucinogen consumption will be found in future studies. “As archaeologists proceed with this kind of analysis, we are likely to discover direct evidence from earlier times,” she says, adding confidently: “There is no doubt.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital